Imagine being able to see what Rosalind Franklin saw, when she and a graduate student first imaged the structure of DNA—and then study the intimate handwritten notes on the back of it.

Now, in fact, you can. A trove of landmark historical science images and artifacts (which also include notebooks, handwritten annotations, and even an inside joke or two), have recently joined the collection of the Science History Institute, a Philadelphia-based museum and library, which is working on making them widely available to the public.

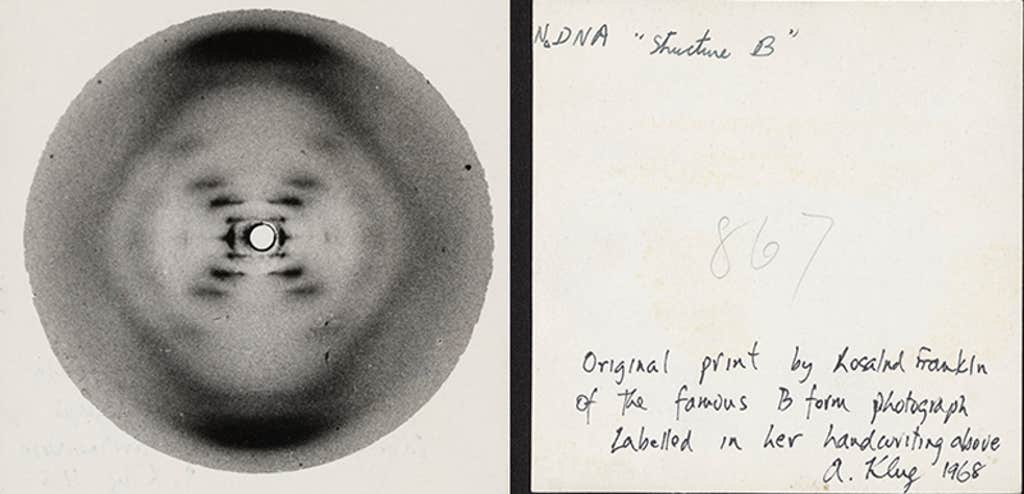

The crown jewel of the collection so far is, of course, the image produced in 1952 by X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin and her grad student Raymond Gosling showing the double-helical structure of a DNA molecule. The “Photo 51” image, which was Franklin’s own personal copy and is annotated with handwritten notes on the back, will be the centerpiece of a new exhibition at the Science History Institute museum planned for fall 2027, which will mark the 75th anniversary of “Photo 51.”

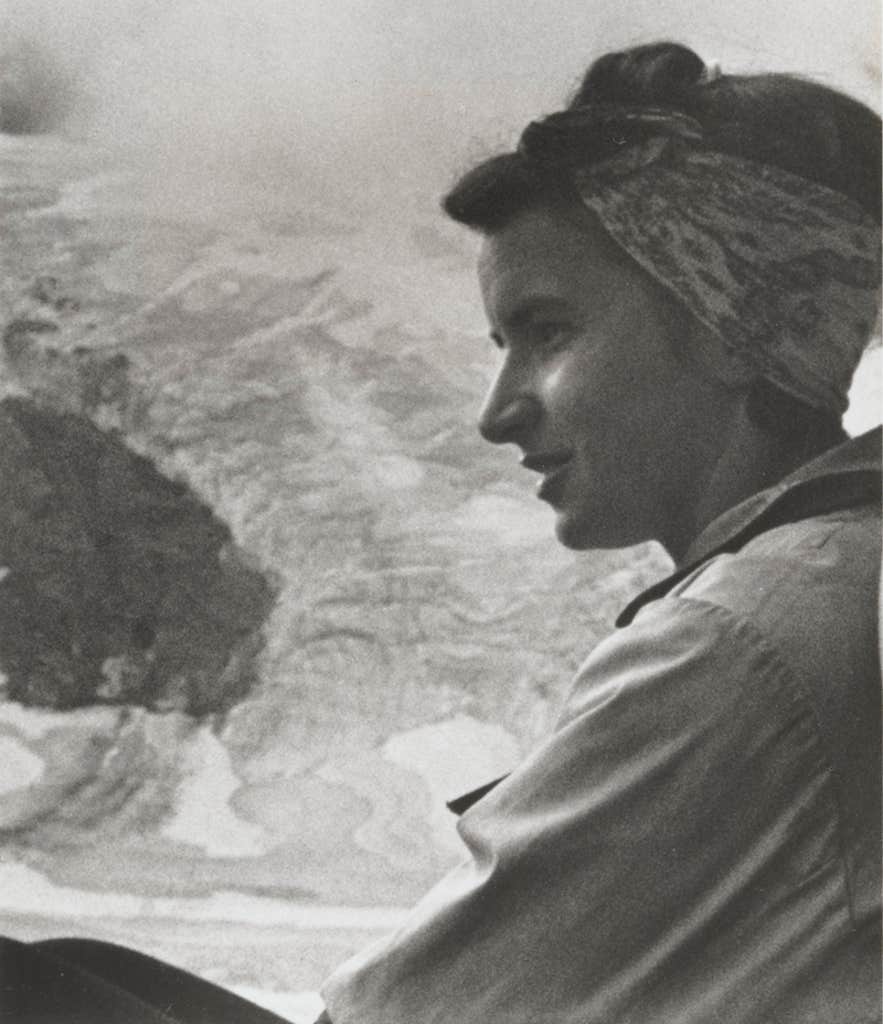

The newly acquired collection features laboratory devices used by Franklin and Gosling in their seminal research, as well as letters, photographs, and other materials from the pair and from other notable molecular biologists of the era. You can also find pictures of Franklin on vacation and even a death notice, written in jest, for DNA’s helix structure (a delightful reminder that even Nobel-worthy scientists like to have a bit of fun here and there).

“We see this as a seed collection that will inspire further growth as we preserve the history of the life sciences for a global audience,” David Cole, president and CEO of the Science History Institute, said in a statement. The History of Molecular Biology Collection was recently acquired from the J. Craig Venter Institute, and staffers at the Science History Institute are at work digitizing the materials it contains, providing free access through their website.

In the meantime, there are more than 140 items already available to peruse and glimpse the inner workings of the people who coaxed revolutionary insights from the hidden worlds that surround us. ![]()

Lead image courtesy of Science History Institute