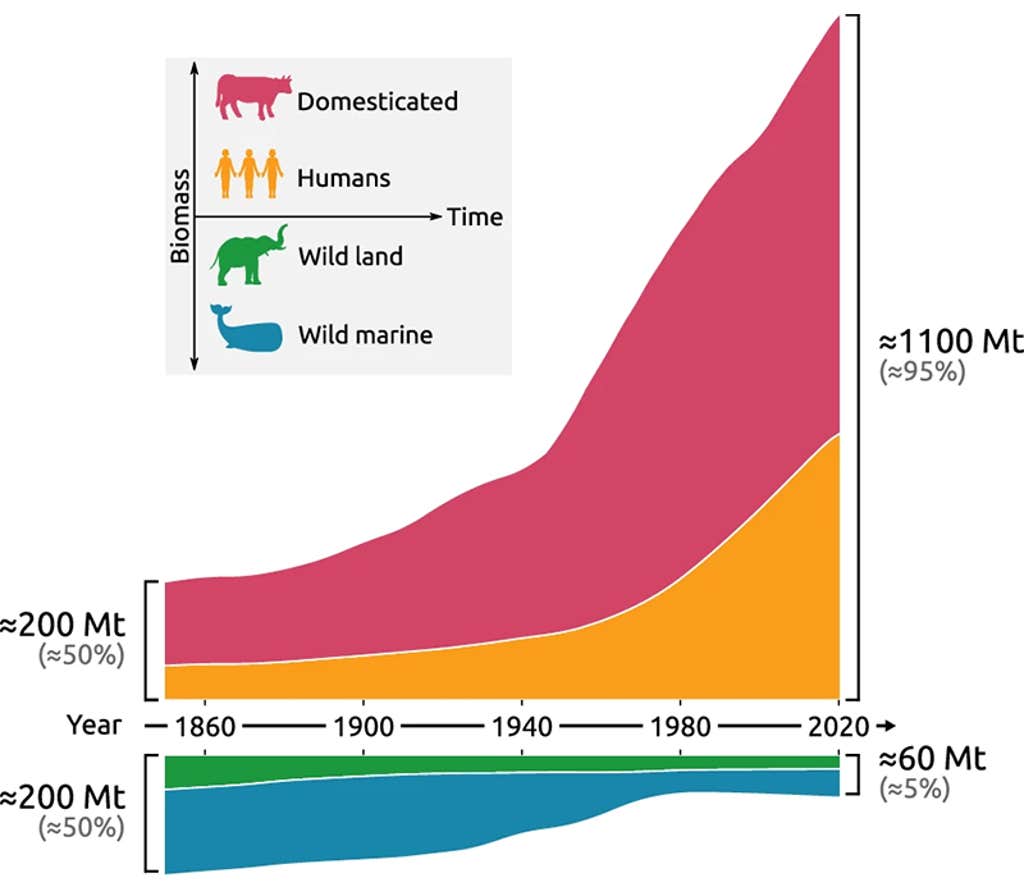

If you weighed all the world’s mammals, how much of that figure—known as biomass—would include wild animals? As of 2020, they contributed roughly 5 percent of the biomass of all mammals, compared to around half in 1850, according to a paper recently published in the journal Nature Communications. As human populations exploded over the past two centuries, our hunger for land and natural resources has drastically reshaped the composition of the world’s mammals.

While scientists often track species extinction as a key measure of biodiversity, the authors write that “this metric only partially reflects the global status of wildlife.” Measuring creatures’ biomass, meanwhile, offers “an integrative global view across groups of species while answering a very basic curiosity-driven question regarding the ubiquity of life.”

Domesticated animals currently outweigh wild mammals tenfold, which puts substantial pressure on natural resources. Raising livestock demands significant amounts of water, land, and feed. Livestock also contribute some 12 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

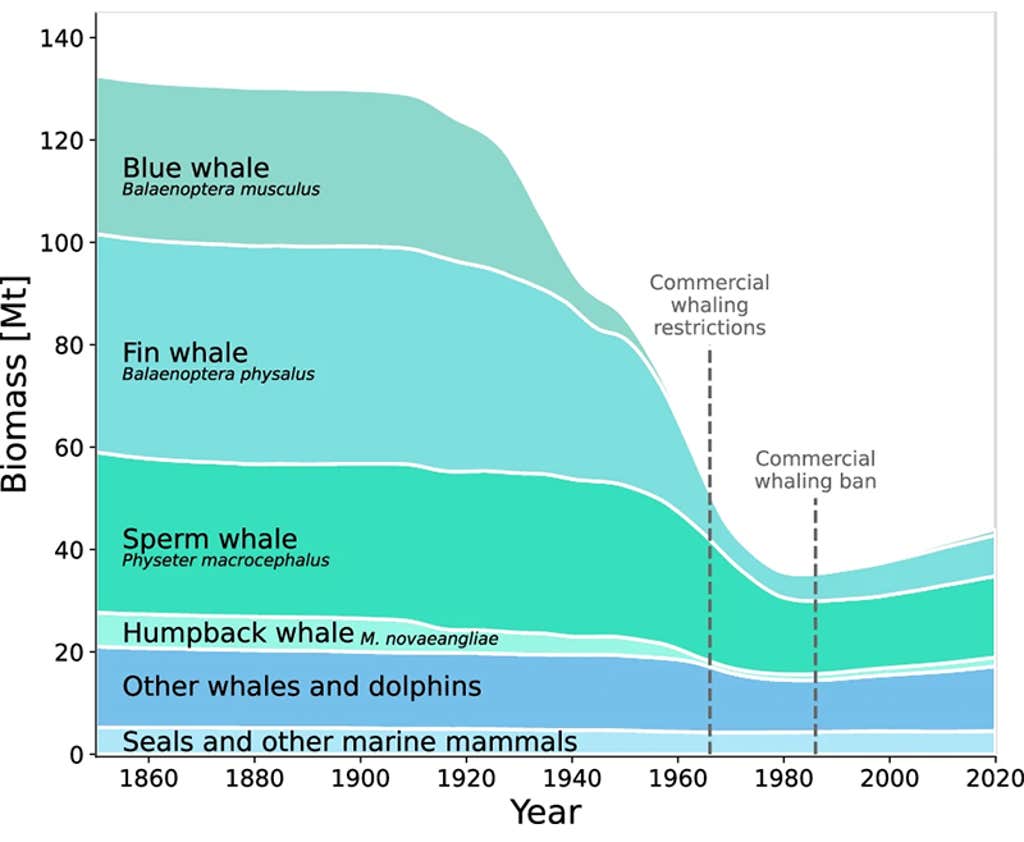

The researchers also analyzed the biomass of wild marine mammals, which has sunk by some 70 percent since 1850—owing to the rise of industrial whaling and “extensive” hunting pressures in the 19th and 20th centuries. But after 1986, when the International Whaling Commission issued a moratorium on the industrial hunting of Great Whale species, such as the blue whale and humpback whale, wild marine mammal biomass began to rebound. Such insights are missed when solely considering species extinctions, the authors of the new study write, because only about 2 percent of marine mammal species have been recorded as extinct since the 1850s.

To arrive at these biomass estimates, scientists from Israel and the United States drew on extensive demographic data for human and livestock populations. But they encountered a dearth of data on wild mammals, and acknowledge that their estimates have limitations. The team combed through the literature to glean historical population estimates of some species, and for wild land mammal species lacking records they “assume that their biomass remained constant since 1850.” To gauge wild marine mammal biomass, they employed a model drawing on population estimates and catch records.

While these biomass estimates are “imperfect,” the authors hope that they can inform future conservation efforts—and tip the world’s scale back toward previous measures. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: fir0002 / Wikimedia Commons