Tens of thousands of years ago, some particularly crafty ancient bees decided to take advantage of the food scraps puked up by owls.

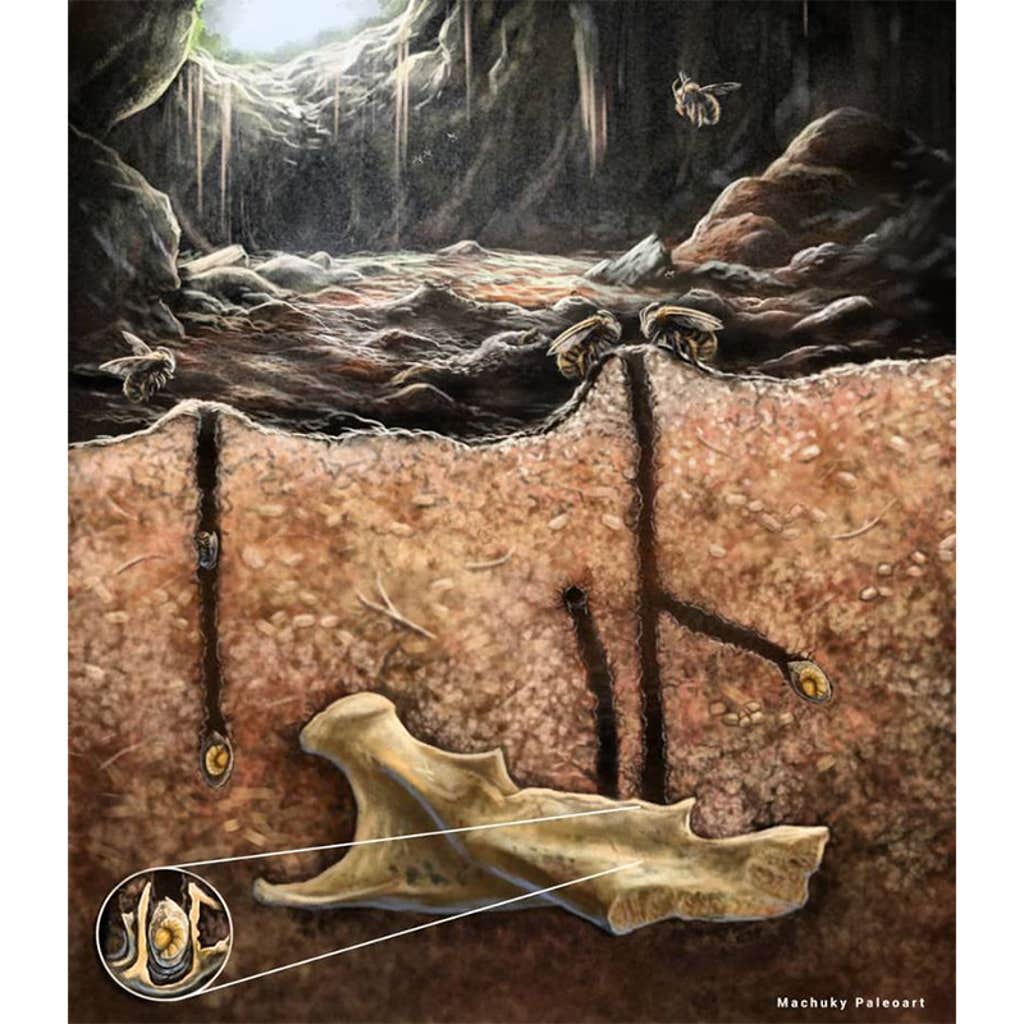

These cleverly recycled remains were discovered in the Cueva de Mono cave in the south of what’s now the Dominican Republic. There, researchers have encountered fossils mainly from rodents, but also some from birds, sloths, and reptiles. This hodgepodge of remains from more than 50 species may have been carried in by predatory birds like owls, who regurgitated pellets containing bones from their prey.

Paleontologist Lazaro Viñola Lopez, who excavated remains from the cave while a doctoral student at the Florida Museum of Natural History, was cleaning possible owl meal leftovers when he observed something odd—sediment lodged in some specimens looked like wasp cocoons. Viñola Lopez and his colleagues scanned these bones to create 3-D images, and noticed that the sediment actually resembled the mud nests that some bee species make today.

They found these concealed cradles in an interesting mix of bones, including part of an extinct sloth’s tooth and bone cavities from the skulls of an extinct rodent. Some nests included bits of pollen snacks for bee babies to consume.

These findings mark the first recorded instance of bees laying eggs in bones, according to a paper published today in Royal Society Open Science. The ancient bees seem to have crafted these tiny nests—each smaller than a pencil eraser—by combining their saliva with dirt. These clandestine structures were built sometime within the past 50,000 years, the researchers estimated, a period known as the late Quaternary. The cozy confines may have kept the bee larvae safe from predators like wasps.

Many bees dig holes in the ground to lay eggs, but these insects may have turned to the cave due to a lack of topsoil on the surrounding limestone terrain. The scarce soil that does exist is washed into caves, where the bees would have encountered plenty of nest real estate.

Read more: “High Mountains, Ancient Shells, and the Wonder of Deep Time”

Viñola Lopez and his collaborators didn’t find any fossilized bees in the nests, but the warm, humid cave environment likely degraded these remains. This means the researchers couldn’t identify which species these insects hailed from.

It’s possible that this mysterious bee species still lives on today, though most of the bones in the study belonged to animals who have vanished. It appears that generations of bees and owls called the cave home at the time.

“This discovery shows how weird bees can be—they can surprise you,” Viñola López, now at the Field Museum in Chicago, said in a statement. “But it also shows that when you’re looking at fossils, you have to be very careful.” ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Viñola López, L., et al. Royal Society Open Science (2025)