Roman soldiers stationed at a fort called Vindolanda in what’s now northern England—not far from the famous Hadrian’s Wall—seem to have run into some pretty severe tummy troubles.

Previously, scientists have dug up evidence of parasites that wreak havoc on the gastrointestinal system at several Roman military settlements, including archeological sites in Austria, Scotland, and Serbia.

Past excavations at Vindolanda have unearthed all sorts of well-preserved items, including wooden tablets that described military activities at the site. Romans lived there between the first and fourth centuries A.D., and troops from all over Europe spent time there. Vindolanda had multiple bath houses over the centuries, and by the third century occupants sourced water from nearby natural springs through an aqueduct. The Romans at Vindolanda also maintained drains and ditches to dispose of water and waste.

This infrastructure makes Vindolanda a prime spot to hunt for parasites, which can spread via food, water, and hands contaminated with human feces and infect dozens of people at once.

To hunt for traces of these pathogens, a team from Canada and the United Kingdom examined sediment from a sewer drain connected to a latrine block at a third-century bath house. They also studied sediment collected from a ditch from the first century, which was part of the fort’s defenses.

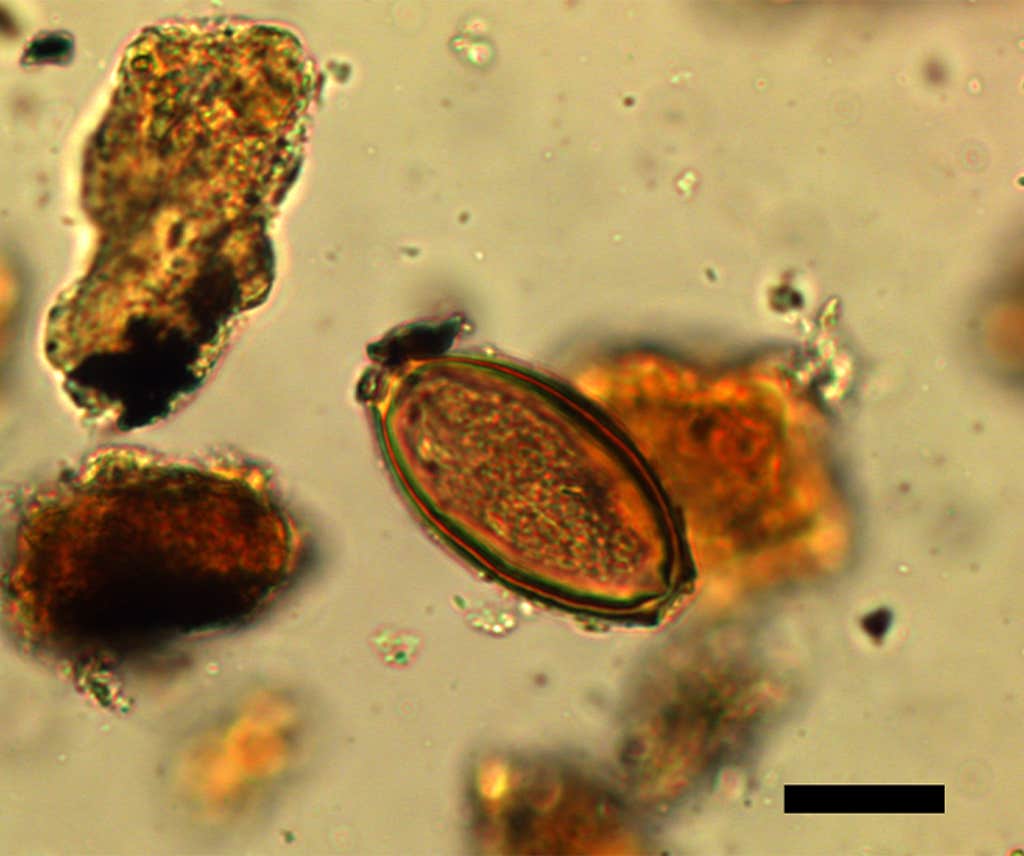

The sediment from both areas contained eggs from parasitic worms called roundworms and whipworms. These infect humans and other animals, and can cause symptoms like diarrhea, pain, anemia, and fever.

They found these eggs in 28 percent of all sediment samples from the sewer drain. In one of these samples, they also identified traces of Giardia duodenalis—marking the first evidence of this parasite in Roman Britain. This ailment, known as giardiasis, is also associated with diarrhea, and can cause dehydration, intense fatigue, and weight loss.

This means that Roman soldiers in the area may have experienced plenty of stomach upset and other nasty symptoms while on duty, according to a new paper published in Parasitology.

Read more: “What Makes Us Bold”

“While the Romans were aware of intestinal worms, there was little their doctors could do to clear infection by these parasites or help those experiencing diarrhea, meaning symptoms could persist and worsen,” said paper first author Marissa Ledger, a biological anthropologist at McMaster University in Canada, who worked on the paper while a Ph.D. student at the University of Cambridge in a statement. “These chronic infections likely weakened soldiers, reducing fitness for duty.”

While the Romans tried to keep things clean at Vindolanda with latrines and a sewer system, “all parasites recovered are spread by ineffective sanitation,” the authors wrote. In these conditions, the soldiers were also potentially vulnerable to other pathogens that spread similarly, like Salmonella and norovirus—which can also make for highly unpleasant trips to the bath house.

Compared with the pathogenic finds from military sites like Vindolanda, previous research has suggested that people in larger Roman Britain urban centers, such as York and London, experienced a wider range of parasites, like meat and fish tapeworms. Such differences hint at the importance of myriad “social, cultural, political, and environmental factors that contribute to transmission on a finer scale,” the authors wrote.

No one said guarding Hadrian’s Wall was easy. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Vindolanda Trust