What’s this?” I said, looking down at the change the old woman had put down on the counter between us. There were bills of the wrong size and color, clunky-seeming coins that were too big and too dull. I stirred a finger in the little pile.

She glanced down herself, then put a hand to her mouth.

“Oh, I’m so sorry, Mr. Duggan. Blame it on age. I forgot. You’re new around here. I—”

I smiled at her. Since Riane and I had moved here to Tarburton-on-the-Moor three or four months ago we’d found that some of the people were prickly and suspicious—“damn’ Yanks”—and others tried to be ingratiating only in hopes of making a buck off us. Or a pound off us, I should say. Old Nettie, who owned the general store but nowadays left the business of actually selling the stuff to her sons and daughters and their sons and daughters, of whom there seemed to be an unlimited and uniformly stocky supply, wasn’t one of the unfriendly ones. From the outset she’d welcomed us, although with the polite reserve of an earlier generation.

“Is it French?” I said, picking up one of the bills. “Ten Shillings,” read the copperplate, dried-blood script.

So the money wasn’t French. I knew enough about the country we’d come to live in, perhaps for the rest of our lives, that I was aware the Brits had once counted their money in pounds, shillings, and pence. What I’d picked up was a ten-bob note, as they’d once said. I’d never seen one before. It looked a bit like a ten-pound note that someone had shrunk in the laundry. The ten-bob note had disappeared when the currency went decimal—back in the 1970s, I guessed. Where once there’d been twenty shillings to the pound and twelve pennies to the shilling, now there were a hundred new pence to the pound… and the pound was a coin, not a green paper bill like the next one I picked up.

“These are amazing,” I said, studying it closely. “Are they still legal tender?”

“It’s a mistake, Mr. Duggan,” Nettie said, trying to brush the money away from me with her hand. “A misunderstanding. Just some souvenirs of the past I keep in the cash register.”

It was obvious the explanation was a lie. Nettie’s face was as wrinkled and dark as a fig, and it didn’t keep secrets well. But of course I couldn’t tell her I knew she was lying to me. I pushed the coins and bills towards her—reluctantly, though, because they interested me.

“They look as if they should be in a museum,” I said. “That’s a half-crown, isn’t it?”

Half a crown. Two shillings and sixpence. Twelve and a half pence in modern currency, except that the half-penny (not to be confused with the old ha’penny coin, which was half an old penny) had been abandoned a while ago. I couldn’t help thinking the Brits could have made life easier for everyone if they’d called their new coins cents, like other countries did. A hundred cents to the pound. Then there’d be no confusion over pennies and pence.

“Some people still like the old money.” Nettie was visibly relaxing a little. It was a Monday morning and there was no one else in the shop except her and me and the smell of shadows. “Money was worth more, back then.”

I imagined it had been. In the days when there had been ten-bob notes, ten bob was worth something. Now they were asking you to put the equivalent, a fifty-pence piece, into parking meters.

Nettie still hadn’t put the heap of old money away. She’d paused, her hand resting on it, and seemed to be having an internal conversation with herself.

“You and Mrs. Duggan,” she said aloud at last, “you’re not planning to be just fly-by-nights, are you? You’ve come to Tarburton to live, haven’t you, Mr. Duggan?”

“For as long as you’ll have us,” I said, grinning. “We like it here. If we ever have kids, this is where we want them to grow up.”

She drew her head back, looking at me through narrowed gray eyes. “It’s about time you hurried up with the little ones, you two. That wife of yours isn’t getting any younger.”

“Don’t let her hear you say that.”

Nettie put her hand on mine. “Can I trust you?”

“Yes. Of course.”

“Then let me tell you what everyone else around here knows. It’s not something I ever do myself, you understand, but…”

Riane’s people had originally come from this part of the world, a couple of generations back, and she’s always talked of Devon and Dartmoor with that curious form of nostalgia people show for places they’ve never in fact been to but with which they feel a sort of inherited familiarity. When we’d married eight years ago we’d planned to honeymoon here—“rediscover my roots,” as Riane put it—but around that time ABC had unexpectedly not renewed Alphonse and Claude for a fifth season (two strongly accented Frenchmen living together in NYC and trying hilariously to pull girls when everybody assumes they’re gay), and so I was suddenly out of a job. By the time my agent had sold the pilot of Birgit and Piotr (a German lesbian and a gay Russian man, both strongly accented, living in Chicago and trying hilariously to pull appropriate partners when everyone assumes they’re an item), we’d had a honeymoon in Wyoming and liked it. Besides, as Riane pointed out to friends when in her cups, we’d only left the trailer twice.

Birgit and Piotr had enjoyed a better run than it deserved. By the time it wound down, to everyone’s great relief, I was writing a children’s show about a family of vampires—you’ve probably not seen it, but I think it’s maybe the best thing I’ve done—and then there was Humphrey the Pussycat, and it seemed I’d struck gold. Humphrey was a quiet hit at home, but where it started breaking records was in the U.K. At last Nickelodeon called it a day, but there was a production company in Abingdon, near Oxford, that wanted to pick up the reins.

All this time Riane had been teaching at MIT. When she was offered a research fellowship at Exeter, it seemed obvious to both of us that we should grab the chance to go live where her grandfather was born. We’d had ideas of a grand old mansion in the middle of the moor, with creaking doors and ghosts and rusty suits of armor, but reality set in fairly fast and we bought a big red house on the fringe of Tarburton instead.

Tarburton was about an hour’s drive from Exeter, which isn’t too strenuous as commutes go. I had script conferences on Humphrey no more than once a month or so in Abingdon, which was a fairly easy journey from Newton Abbot, the nearest rail hub. We could drive to the moor in less than five minutes, walk to the nearest pub in three. And, despite the unfriendliness of some of the natives, we loved it here.

I can’t believe I’m doing this,” said Riane. “Correction. I can’t believe I’m allowing you to do this.”

I knew what she meant. There are things that the creator and scriptwriter for Humphrey the Pussycat can do that are taboo to researchers attempting to reconcile string theory with General Relativity, one of Riane’s current bugbears. It wasn’t so much that she knew that what Nettie had told me was a physical impossibility, more that she knew the physics was several orders of magnitude more complicated than I did.

It was a pleasant summer evening at the edge of Dartmoor. We were probably about a mile away from where, a few weeks after we’d arrived in Tarburton, Riane and I had spent a pleasant hour or so in the darkness of a warm night “testing Dartmoor to see if it worked,” as Riane put it. It hadn’t, luckily: Neither of us wanted kids, whatever Nettie might think.

That’s what we usually do with wonderful things, we humans. We take the marvels of quantum mechanics and use them to watch reality TV.

I fetched out of the trunk of the car the big metal can that Nettie had lent us. It looked suspiciously rusty in all the wrong places, but the fact that the metal was painted brown made that seem somehow less worrying.

“5 GALLONS” was embossed on the side of it.

Those were five British gallons. The British gallon is twenty-five percent bigger than its U.S. counterpart. This sucker was going to be heavy by the time I’d filled it.

Far in the distance I could see a little posse of Dartmoor ponies feeding unconcernedly. Right beside where we were standing was an ugly aluminum gate with a big padlock on it. The gate was festooned with yellow tape and a couple of ugly big black-on-yellow metal signs saying:

DANGER

Keep Out!

Unexploded Ordnance!

The signs bore the marks of a few seasons’ weathering by the elements, which would have been a bit of a giveaway if any tourist had paused to think about it, but presumably none of them had—they’d all been only too keen to put as much distance between them and the unexploded bomb as possible.

“Well, see you soon.” I shrugged in a way that I hoped made me look nonchalant. In fact I was terrified—terrified of what was about to happen if Nettie had been telling the truth, possibly even more terrified that this might be her idea of a joke, that suddenly Riane and I would be surrounded by a derisive horde of the locals, jeering at the two dumb Yanks.

Riane crossed her arms under her breasts, hugging herself. She shivered, although the evening wasn’t cold.

“Get going, will you?”

“Wish me good luck?”

“Good luck.”

“A goodbye kiss?”

She pecked my cheek brusquely.

“A final message?”

“If you’re not back here within ten minutes you’re in trouble, mister.”

So, using the key Nettie had given me, I undid the padlock. The gate opened on well oiled hinges. The empty gas can clanking against my knees as it tried to trip me up, I shut the gate firmly behind me, leaving it to Riane to redo the padlock.

Then I took one small step forward, another to the left (widdershins), and let myself stumble into full daylight.

So that explains why the Shell on Bratherton Street never does much business,” said Riane. We were sitting in the White Lion with pints of Guinness and plates of shepherd’s pie. The Shell was the only gas station between here and halfway to Newton, and most of the time it looked deserted. It survived on auto repairs and passing tourists.

Cheap gas. It seemed such a trivial way to use something so wonderful as what I’d just discovered, thanks to Nettie. And yet that’s what we usually do with wonderful things, we humans. We take the marvels of quantum mechanics and use them to watch reality TV.

I’d tripped and landed face-down on spongy grass with the metal gas can half under me, bruising my stomach. Nettie had told me to hold it out to my side, and of course I’d forgotten.

I picked myself up, swearing softly at the pain, and looked around me.

I was standing next to a stretch of gray road that wound its way in slow curves across the moor. There were half a dozen small clouds in an otherwise flawless blue sky. As near as I could guess, the sun was directly overhead. Away in the distance I could see two black dots moving—a pair of hawks, circling for prey. About fifty yards from where I stood was a sleepy-looking gas station.

Clutching the rusty canister firmly I began walking.

On the edge of the gas station’s forecourt was a sign with big yellow-on-black capital letters that read:

TWO-STROKE

TOILETS

I grinned nervously. Two-stroke toilets? What gives? Some kind of Congressional trysting place?

It was the kind of silliness I needed right then. The scene was peaceful, and yet the very fact that I was here at all was so completely wrong that my back-brain was telling me I should be turning and running as far and fast as my legs would carry me. I was breathing in little short gasps, as if I’d just carried something heavy too quickly up a flight of stairs. But I made myself keep going until I was past the perplexing sign and crossing the cracked forecourt to the pumps.

Even then I think I might have turned tail if I hadn’t seen Dr. Wallen, the older of Tarburton’s two GPs, inside the little sales kiosk between the two pairs of pumps, talking amicably to the woman there as she sold him a couple of packets of cigarettes. Wallen suddenly noticed my arrival and glanced at me as if I’d caught him committing some guilty act—which of course I had. A doctor. Cigarettes. Verboten. Very, very verboten back at home in the 21st century, even in Tarburton.

Because this wasn’t the 21st century I was in, not any longer. Even if Nettie hadn’t warned me what to expect, I think I’d have known it the instant I fell through the gap between evening and daylight.

Dr. Wallen came out of the booth and nodded to me. “G’day.” There was something different about him, but I couldn’t immediately identify what it was. He picked up his own gas can and, carrying it with much more ease than I’d have expected, began to make his way along the side of the road in the direction from which I’d just come.

The woman he’d been speaking to emerged and walked towards me, wiping her hands together with a grimy cloth.

“Can I help you?”

She had bright rust-colored hair, lots of it, tied back from her face. A broad face with very pale skin and a thousand tiny orange freckles. She was wearing faded brown overalls. Later it’d occur to me that she was extremely pretty, but at the time I was too unsettled to notice.

I gestured at the big brown can I held.

“Of course,” she said, taking it from me.

As she bent over filling it—I’d chosen the higher grade of gas (petrol) because the difference between four shillings and eightpence for the regular and four shillings and elevenpence for the super seemed trivial—I drifted into the booth. Besides the cigarettes (odd brands like Player’s Weights and Park Drive that I only half-recognized), there was a selection of candies (Smarties, Mars Bars, Fry’s Five Boys Chocolate) plus a couple of copies each of the Daily Mirror and the News Chronicle.

I didn’t notice the headlines, just the date. Today was the 14th of June, 1958.

“All done,” said the young woman, smiling. She’d come up behind me without me noticing. “That’ll be twenty-four shillings and tenpence, please.”

Even though I’d practiced with the old money Nettie had given me, the red-haired woman still had to help me before I got the exact amount sorted out. I wondered if I should give her a tip and then decided against—she was so friendly she might take offense if I tried to press a few of the clumsy old pennies into her hand.

“Do you do much business?” I said by way of conversation as my money vanished into the till.

“We don’t do badly.” She had an open smile and sparkling green eyes. “Dad keeps saying we should close the place down and go and run a pub somewhere, but we do all right. There’s not so many cars, out here on the moor, although July and August get busy. But then there’s the foot traffic, like yourself. Cigarettes?”

“I don’t smoke, thank you.”

“Wise man. It’s a filthy habit. I keep trying to give it up, myself, but it’s something to do in between customers.” She gave a rueful shrug.

We talked a few minutes longer—it was clear that business was slow enough she was glad of the company—and then I was lurching back along the road. Dr. Wallen was obviously far fitter than I was, because he’d managed his burden with considerably more ease. I was overly conscious that Lin—as she’d told me her name was—must be watching me, perhaps putting a hand up to cover her smile.

Screen writers don’t get nearly as much exercise as they should, I thought. But, if I was going to make a habit of buying cheap gas here in 1958, I would surely start building up the muscles. I’d have to. The distance back to the gate seemed to get longer rather than shorter with every pace I took.

At last I was there, though.

You couldn’t see the gate from this side, just a couple of worn old bricks in the grass that Nettie had told me to look out for.

I put the heavy canister down for a moment, bending over with my hands on my knees as I struggled to get my breath back.

Then I picked it up, stepped up onto the bricks, twisted toward my right, and found myself facing a worried-looking Riane on the other side of the gate.

“Back so soon?” Then she saw how heavy the can was, and nodded. “Tell me when we get home.”

“Did you see Dr. Wallen?” I said.

A little line of puzzlement appeared on her forehead.

“No,” she said. “Should I have?”

Ernie Bainton, a candidate for Tarburton’s chief village idiot—although there was some fierce competition for the slot—was beginning to get rowdy at the bar, a sure sign that he was about to become pugnacious. Since one of the targets of his pugnacity could all too easily become the “damn’ Yanks,” we finished up our suppers and left. Outside on Church Street the night was quiet, with few cars about. Lights in upstairs windows indicated the kids were in bed, or getting there; there was a dimmer, flickering light in many of the downstairs ones. An orange moon hung ahead of us, low over the horizon. It was almost impossible for me to reconcile the mundane tranquility of the scene with the fact that, just a few hours ago, I’d been breathing the air of over fifty years ago.

“What are you going to tell them at the university?” I asked Riane as we ambled along arm-in-arm.

“Nothing,” she said. “Not yet, anyway.”

“But don’t you feel it’s your responsibility as a physicist to—?”

“I probably will, eventually. But for now I have responsibilities as a Tarburtoner, too.”

She didn’t have to say any more. The people around us—the kids in their beds and their parents slumped in front of the TV—weren’t exactly our new family, but we did owe them some kind of loyalty. Nettie had trusted us not to broadcast the town’s secret to the world. We couldn’t ignore that trust.

“Do you have any explanations for it?” I said. “Wormholes? Folds in time? The contemporaneous intersection of higher-dimensional nexuses?”

She chuckled. “You borrowed that last from Humphrey.”

“He borrowed it from me. If you think about it.”

We walked on a few more moments in silence.

“I try not to start forming hypotheses until I have evidence,” she said. “At the moment all I know is that, yes, if you step through a particular… gateway… if you step through a particular gateway just right you find yourself in 1958. It’s an impossibility, of course. Except you did it, darling, and you came back with the fully leaded gasoline to prove it. And then I took a look for myself, and was even able to buy a tube of Smarties for threepence. So clearly the impossibility isn’t impossible at all. But I can’t even begin to start guessing what’s going on…”

She kicked a loose stone into the gutter. It skittered with a noise like fleeing cockroaches.

“I’ll probably not sleep at all tonight, Tommy. And if I do I’ll have nightmares.” She smiled wearily. “Oh, the joys of physics. This is at one and the same time the most exciting thing that’s ever happened to me and the most frightening. There’s a lot of stuff that’s going to have to be rewritten, basic stuff. Stuff we all thought we knew but we obviously didn’t.”

There’s an idea in the Koran that Allah recreates the universe in every single instant. There’s no such thing as the passage of time, just an infinite succession of Nows.

I laughed. “You’re right. I get it easy. All I need to know is that it happened, that it’s real. Though I’d like to know what two-stroke toilets are.”

She squeezed my arm. “If it’s any consolation, I don’t know either. We can look it up in Wikipedia when we get home.”

“Wikipedia? Is that what we pay you fancy-dandy research physicists for?”

A few minutes after we’d gotten home, while I was digging out the glasses for us each to have a scotch, I heard Riane laughing hysterically. I went through to the living room to find her sitting in front of her laptop, the bright display lighting up her face.

“Okay,” I said. “Break it to me gently.”

“The toilets are a separate item.”

“Come again?”

“The sign tells people the gas station has toilets, and also that they can buy two-stroke there.”

I put the glasses down on the coffee table and then headed for the kitchen to fetch the bottle. When I got back with it I said, “So what’s two-stroke?”

“It’s the fuel you use in a two-stroke engine.” She raised a hand to stop me asking the obvious question. “Most internal combustion engines have a four-stroke cycle. The piston goes twice up and twice down the cylinder for a complete cycle. In a two-stroke it’s arranged so the whole cycle can be done with a single up-and-down movement. Look”—she pointed at the screen—“Wikipedia even has a natty little animated diagram.”

I looked, then read a few lines. Two-stroke engines could be a lot lighter than four-stroke ones for the same energy yield, but their exhaust emissions were obscene. No wonder they’d largely been phased out of this greenhouse-gas-aware world. Back in the 1950s, of course, no one except maybe a few climatologists had heard of global warming, so what did emissions matter? No one had thought too much, either, about what the lead in those emissions might be doing to people’s brains. The more we learn, the more frightening the world becomes.

“Motorbikes, lawnmowers, that kind of thing,” Riane was saying. “When the stuff’s used today the gas is usually cut with vegetable or synthetic oil, so the environmental effects aren’t so dire. Even so . . .”

I poured us each a couple of fingers of liquor, then added an extra finger to my own glass. Riane wasn’t the only one who might have difficulty sleeping tonight.

The next day was a Saturday, so Riane was with me as I returned the key and the gas can to Nettie; she’d been expecting us, I supposed, which was why she was serving in the shop again. As always on a Saturday morning her store was quite busy, mainly with people picking up items they’d forgotten to buy more cheaply the night before at the big-box stores outside Newton and Exeter.

“How long has this been going on?” I asked Nettie in a low voice at a moment when the place had temporarily emptied out.

The can had vanished as if by magic. She’d left the little brass key on the counter.

“Years,” she said. “Ten? Twenty? Who counts?”

“Can we go back there again?”

“Why not?” The old woman nodded in the direction of the window. “Ronnie Gibbs will cut you a copy of the key. And sell you a canister. Make sure he doesn’t try to sell you one of they plastic ones. They didn’t have they, back then.”

Ronnie Gibbs owned the Tarburton hardware store. There was a sign in his window that read

You Won’t Believe Our Prices!

and it was nothing but the truth. For obvious reasons, he was known locally as The Robber, or The Boy from Brazil, or just plain Biggsie.

“I’d better take out a second mortgage,” I told Nettie.

She gave me a frosty smile. “Tell him I sent you.”

And, sure enough, a few minutes later we were getting discounts big enough that Ronnie’s prices were only about twice what we’d have paid in Newton.

Once I’d returned the original of the key to Nettie, Riane and I trudged back along the High Street. We got the occasional curious look, but by now most people knew who we were. I was gratified that some of the looks Riane got were, as usual, not just curious but appreciative. Her grandfather, the one who’d come from one of the nearby villages, had been of Cornish blood, and had the small darkness of many of the Cornish people. His wife, Riane’s grandmother, married after gramps had moved to San Francisco to haul sacks of grain on the docks, had been a Thai. Their daughter, Bella, had married an African American with a dash of Irish. When I’d first met Riane I’d told her she was either an angel or a stranger from another world or just a top-quality mongrel. She’d chosen mongrel: as she’d pointed out, mongrels are always the best and most faithful and loving and intelligent of dogs.

“And you can pick them up at the pound,” I’d added.

Sometimes we went together to buy Lin’s cheap gas, more often I went on my own while Riane was in Exeter. Occasionally Riane gazed wistfully at the cigarettes and murmured to me, “Almost makes you wish you smoked, doesn’t it?” We stocked up on cheap candies, too. Some of these were hard and sticky and dangerous to teeth; covered in sugar crystals, they were kept in big glass jars and sold by the quarter-pound in little white paper bags: pineapple chunks, which were bright yellow on the outside, pear drops, which were a dangerous-looking green, and my own personal favorite, acid drops, which were a sort of pearl gray and tasted like one of those rare cough medicines you actually like. We once bought a copy each of the Mirror and the Chronicle, but only once. It was always June 14th when we went to Two-Stroke Toilets, so why buy the same paper twice?

“I have a conundrum for you,” said Riane one Friday night when I’d returned with a can of gas in back of Trudy, our little Smartcar. My favorite theoretical physicist had been drawing little diagrams in a notepad while waiting for a casserole to cook.

“You have?” I said warily.

“Let’s take a conservative estimate and say that a thousand of our fellow-Tarburtoners are buying their gas—at least sometimes—from Lin.”

“That seems reasonable.”

“And let’s say they’re doing it on average every couple of days—in fact, let’s say the average is about 1.825 days, just to make the math easier.”

“Two hundred trips apiece each year,” I said, sitting down opposite her at the kitchen table. I took a gulp of the warm beer she’d been drinking.

“Yep. So that’s two hundred thousand visits to Two-Stroke Toilets every year from 21st-century Tarburton, all told. And everybody’s going to June 14th, 1958. But people have been doing this for years—twenty years, maybe? Call it four million visits, or thereabouts. Four million people a day going to and fro along that little stretch of road. Where are they all? We hardly ever see anyone else there from our own time. How could Lin fill four million gas cans in a single day? And where would all the gas come from? Twenty millon gallons of the stuff? Why isn’t the grass by the roadside trampled into oblivion? Why haven’t those two bricks at the”—she looped her hand around in the air as she sought the right word—“those two bricks at the portal. Why haven’t they been worn down to dust?”

“Maybe not everyone arrives on the same day?” I suggested. “It’s always June 14th, 1958, for us. Perhaps for other people it’s June 15th, or 1959, or who knows?”

People in Tarburton didn’t talk much about their supply of cheap gas, so it was difficult to compare notes. I think the locals figured that, if they spoke about Two-Stroke Toilets among each other, sooner or later the news would leak to the outside world, and after that there’d be havoc. If it hadn’t been for Nettie accidentally giving me change from the wrong drawer of her till and deciding Riane and I could be trusted, we could have lived for decades in the village and never known.

Riane shook her head irritatedly. “That would reduce the problem a bit, but only by a matter of degree. You’re still looking at a major logistical problem—and one that should be getting worse all the time.”

I went and fetched a beer for myself from the fridge, and a replacement for Riane, too. She nodded her thanks, took a pull, waited until I was sitting down again.

“But even that’s not the strangest thing,” I said.

“The strangest thing of all,” she agreed, “is how come we never meet ourselves?”

I could see that half the figures with which she’d been filling up the pages of her notebook were diagrams with lots of arrows and question marks or equations that looked to me like untidy bundles of barbed wire. The other half were doodles of Snoopy. She only ever doodled Snoopy when she wasn’t just baffled by a physics problem but profoundly worried by it.

“Maybe we eventually will?” I said. “I’ve only been there twenty times, maybe thirty. You’ve come along with me less than half that many. Each visit doesn’t last more than ten, fifteen minutes…”

The past’s just like the future—it’s made up of an infinite number of possible courses.

My voice trailed away. I always arrived not just on the same day but at about the same time. However I looked at my own math, I should have run into my own alter ego by now. Something else that had been bothering me came to the surface. Lin treated me like a new customer every time I appeared. Sometimes I thought I saw a flicker of recognition in Lin’s eyes, but that was probably just me flattering myself. She was a pretty girl.

“It’s as if there were millions of different June the 14ths, 1958,” said Riane, recognizing my frustration.

“But that can’t be, can it?”

“No. Yes. Perhaps. Maybe.” She drew a vicious line through one of her equations, tearing the page with the point of her pencil. “It depends on what you mean by the past. Let’s get some food inside us.”

We didn’t say much as we ladled steaming chicken stew onto a couple of plates. I cracked a bottle of the cheap Shiraz we both liked. Riane lit candles. All very domestic.

“Mary Cranston, one of the people I work with,” she said eventually, holding out her glass for a refill, “believes we’ve got our ideas of the past all wrong. We think of the future as a sort of infinite fan of branching possibilities. Probabilities, rather. We can make guesses about which of them might be more likely than others, but we can’t say for certain which if any of them will happen. The past’s different, though. The past has already happened. So we think of there being just the one past—a single road that brought us to where we are.”

My wife was silent a moment as she chewed, swallowed.

“Mary says that’s a big mistake, and she has the math to prove it. She says the past’s just like the future—it’s made up of an infinite number of possible courses. We can guess at which one of them did happen, but we can’t be sure. Her math’s very beautiful. There’s this lovely symmetry either side of the present.”

Riane gestured with her two hands as if she were comparing the weights of two apples. “The past,” she said, raising her left hand. “The future.” She raised the other. “According to Mary, we should all become Now Chauvinists. The Now isn’t just another instant in an endless succession. It’s the constantly moving balance point, the center of symmetry, between the past and the future. If you go back to the past you can expect Two-Stroke Toilets to be in only a tiny fraction of a myriad June the 14ths, 1958. That still means a hell of a lot of… of…”

“Of Two-Stroke-Toilets-containing-June-the-14ths-1958,” I said. “Sounds like something out of Dr. Seuss.”

“Yes. Sooner or later we may very well meet ourselves. There’s not so many matching locations that the chances of doing so are zero. And we can expect to keep on meeting other people from today’s Tarburton when we’re buying gas. I wouldn’t be surprised if we met someone who’s dead.”

“Dead?”

“Dead in our time. The Tarburtoners who go to Two-Stroke Toilets to get their gas could be coming from any time after the gateway was discovered.”

“Or any time in the future,” I said. “I haven’t noticed anyone with a jet pack, have you?”

She looked momentarily puzzled. Then I could see her pushing that to the side of her mind as a conundrum to be ignored for now, pulled out for re-examination later.

“All those different summer days,” I said thoughtfully.

We grinned winily at each other.

I felt my grin fading. “But I don’t see it,” I said. “Not really. I can remember what happened yesterday. There was only one of it.”

“Was there?” Riane’s eyes were shining with amusement in the candlelight.

I thought for a few moments.

“You have a point,” I said at last. Perhaps my recollection of yesterday was just the single story my mind had chosen to believe. “So you think that every time we go to Two-Stroke Toilets we’re visiting a different possible past?”

“Something like that, yes.”

“Only something like that?”

“There’s an idea in the Koran,” said Riane. “that Allah recreates the universe in every single instant. There’s no such thing as the passage of time, just an infinite succession of Nows, each of them being a special creation.”

“You’re losing me.”

“It could be that, each time we think we’re going back to June the 14th, 1958, what’s really happening is that we’re creating a new universe.”

“Do you really believe that?”

“What I believe or don’t believe isn’t relevant. But the math is even more beautiful than Mary Cranston’s. And if you put both of our notions together—because there’s no reason why they shouldn’t both be true—the math gets yet more beautiful still.”

She picked up her notebook and leafed back a few pages, then held it out to me. The paper was covered with what looked, in the uncertain light from the candles, like a plate of spaghetti as drawn by Jackson Pollock in a foul mood. With a Snoopy in the corner.

“That’s beautiful?” I said.

Riane laughed. “It’s all in the eye of the beholder.”

Two days later it was a Sunday. The papers had come whumping in through the letterbox in the usual way, and I’d gone and fetched them, pausing for a pee on the way back to bed before climbing in beside a still-snoring Riane. On the table by my bedside I had a copy of Chambers’ Dictionary and a collection of pencils and pens. One of the olde worlde addictions we’d developed was the Azed crossword in the Observer.

I’d been sleeping poorly, the past couple of nights. After Riane had finished explaining to me how she thought the passage of time really worked, I’d drunk enough Shiraz to make sure I was three-quarters asleep before I fell into bed, luckily at the first attempt. But I’d awoken at two or three in the morning, watching the trees and the moonlight make dancing pageants on the bedroom wall while outside cats fought and foxes barked. For hours I just lay there, trying to persuade myself I was dreaming up creative ideas for the new season of Humphrey when in fact all I was doing was panicking, the same old dreary thoughts chasing around and around in my head like Ben Hur on his track, getting nowhere. Finally I’d gotten to sleep in the dawn.

Last night had been a repeat of Friday, although without the benefit of the Shiraz. Both nights, Riane had slept like a child. I supposed she was used to her own ideas.

This morning I got nowhere with the crosswords.

If you hopped into a time machine and went back to the past, you could do anything there you wanted without creating rafts of paradoxes.

What Riane had tried to explain to me was that, rather than existing in a single universe, moving according to the dictates of a forward-pointing arrow of time, our existences were more a matter of sliding sideways through an infinite number of probabilistic universes, each one differing in slight detail from its neighbors. For convenience, our minds labeled these as moments of the past and future. Mary Cranston’s notion of Now Chauvinism still held good, because in any instant there was just a single reality, condensed out of the vast probabilistic array.

I could get my head around these ideas so long as I kept them in the abstract. As soon as I started relating them to myself, though—that was when the panic started. Because what it meant, surely, was that there wasn’t just one of me—just one Tommy Duggan—but an infinite number, one for every universe my consciousness slid through.

Riane didn’t see this as an assault on her identity, but I was less sanguine. It made me feel vulnerable, threatened, and in an odd way horribly alone.

There was another consequence that she’d explained to me, assuming her own and Mary Cranston’s “beautiful” mathematical workings were correct. If you hopped into a time machine—which was effectively what we were doing—and went back to the past, you could do anything there you wanted without creating rafts of paradoxes. You wouldn’t come home to find yourself in a drastically altered version of the present, like in the old science fiction stories. All you’d have done was tweak one of countless possible pasts a little.

After a time Riane woke, and reached out for me. While I was holding her in my arms the fears receded. Surely this was the only reality that mattered. Her warmth.

We had a snack lunch at the White Lion—a basket of scampi, tartar sauce out of a jar—and then pottered out of town in Trudy.

“Coming with me?” I said as we rolled to a halt by the padlocked gate.

“You bet.” Riane gave an exaggerated shiver. It was a chilly day. On the other side of the gate, June 14th, 1958, would be pleasantly warm, as it always was.

“Come on, then.” I fiddled with the key in the padlock, and a few moments later we were ambling along the road towards the familiar sight of Two-Stroke Toilets.

From somewhere we heard the sound of youthful and drunken voices raised in song: “She’ll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes…” There was an atrocious gear change at the end of the line.

We smiled at each other nostalgically. It wasn’t so many years since we’d been teenagers and the world was a place to fill with noise.

My shoelace broke. “Damn!”

Riane started laughing at me as I limped another pace or two.

“Here, dammit, woman.” I passed her the empty gas canister. “Mock me, would you? You go on ahead and start filling her up. We’ll talk about punishment later.”

“Oo-er,” she said, taking the can.

“And get me a bag of acid drops, why don’t you?” I called after her.

I knelt down to try to repair the lace. Even as I did so, I think I had a sense of the inevitable sneaking up on me, but I shook the feeling away. It was too nice a day. There were birds singing and little white clouds scudding. There were kids in a car celebrating their hormones. The air was…

“She’ll be wearing pink pajamas when she…”

Wait a moment. Kids in a car celebrating their hormones?

They’d never been here before. It was always roughly the same time of day when we came to Two-Stroke Toilets—always noonish. I squinted up at the sun, high in the sky. Nothing should ever be different.

This wasn’t June the 14th, 1958. Couldn’t be.

The car shot past me as I was pushing myself to my feet. It had an open top, and I saw a glimpse of three close-cropped heads and some bright clothing.

The driver made some attempt to slow as he reached Two-Stroke Toilets—I assume he wanted to stop for gas. Whether he got his foot caught between brake and accelerator or what I don’t know, but the car must have been doing sixty or more when it hit the little row of bricks at the front of the forecourt and, tilted up at a crazy angle, careened straight into the front pair of pumps.

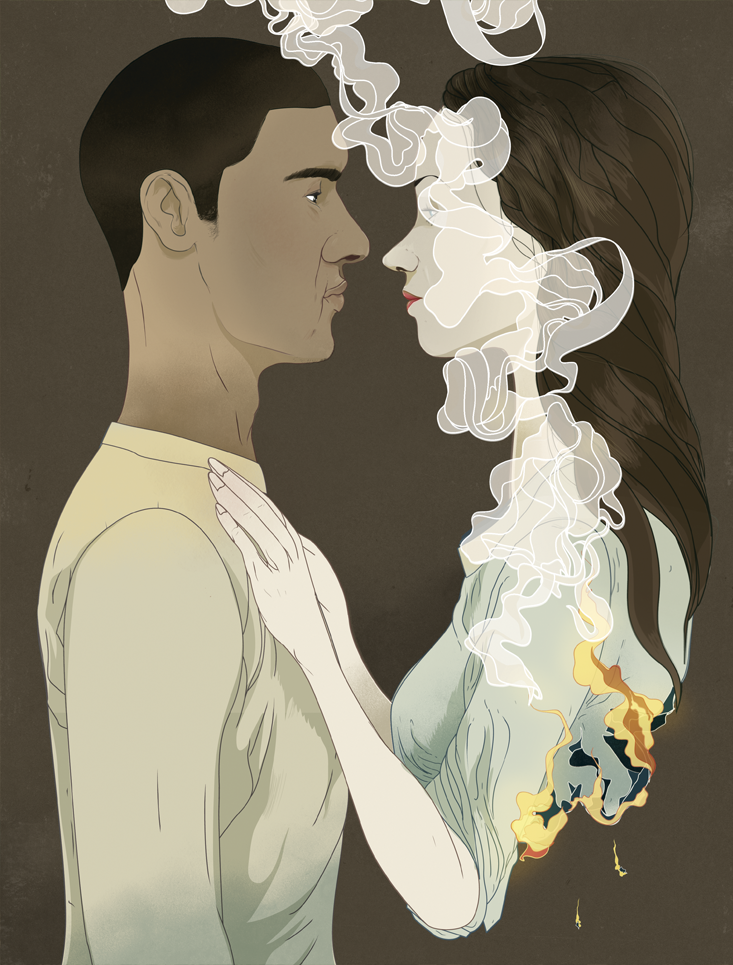

Where Lin and Riane were. Riane was bending down to unscrew the cap from the gas can while Lin was reaching to pluck the nozzle from its cradle. They looked up the instant before a couple of tons of screaming metal hit them.

I was screaming too. I’d kicked away the unlaced shoe and was running at a hobble towards the carnage when suddenly one of the pumps went up in a fireball. Lin must have tightened her grip on the nozzle in the instant of her dying.

Moments later, the other pumps erupted—one, two, three mushrooms of flame.

I tried to force myself closer, believing there was a chance I could pluck Riane from the inferno even at the same time I knew it was futile, that I’d just be killing myself as well. The heat took the decision away from me, beating me back no matter how hard I struggled against it. My throat was raw from the fumes and the airlessness and my own screams. The roar of the flames engulfed the world.

I collapsed into darkness.

Quite how long it was before I opened my eyes again I can’t tell. I suspect it was no more than a few minutes. The conflagration that had once been Two Stroke-Toilets seemed to be a little less greedy, but that might just have been because I could hear nothing. A huge column of black smoke climbed into the sky, and must have been visible for miles around. Soon there would be other people here—tourists, cops, firemen.

Some instinct picked me up and forced me to walk back towards the portal. I don’t know how I got there. There were small burns all over my jeans and sweatshirt. Some embers still smoldered; I could see them, register them, but didn’t have the presence of mind to know how to slap them out.

Up onto the two bricks.

A small rightward turn.

Home.

My hand seemed to sizzle when I put it on the rough metal of the gate, and I shrieked like a child.

I have vague, strobed recollections of driving back through Tarburton. I didn’t see streets or people: just a darkening, twisting tunnel at whose other end was the big red house Riane and I had bought.

I couldn’t find my front-door key. I knew it must be in one of my pockets but I couldn’t locate it instantly and my hands were hurting too much to let me probe deeper.

Except—except, I abruptly noticed, my hands were pristine, unscathed. I’d thought they were scorched from the heat, burned where embers had landed on them.

It didn’t matter. They were in anguish.

I threw myself against the door, yelling in pain, yelling though each cry was in itself a new agony. Someone came out of a house opposite to watch. I didn’t care.

And then the door wasn’t there any longer.

Someone had opened it.

Riane.

“Whatever’s going on?” she said, wiping sleep from her eyes with the back of a hand. “Are you all right, darling? Where have you been?”

Riane still lives in Tarburton and works in the Physics Department of the University of Exeter, although she has a full professorship now. Her colleague Mary Cranston was tipped for a Nobel because of her theoretical work on the nature of time, but died unexpectedly; since the award is never given posthumously, it went to someone else. Riane’s parallel work has remained far more controversial. Both hypotheses go a long way towards explaining dark matter and perhaps dark energy. Riane is still my favorite theoretical physicist and we have long and frequent phone calls full of laughter and sometimes tears, but I can’t live with her, not after seeing what I saw.

I’m living in New York City these days. Humphrey the Pussycat finally came to the end of its useful life—it lasted about one season past that end, to be honest—but luckily Rudolf the Magnificent (about this superhero rabbit who’s, like, fat and stupid) saved my bacon. Now I go to script conferences near Times Square rather than near Oxford.

Riane was disbelieving when I tried to tell her what had happened. She went whiter than I’ve ever seen her, clearly assuming I’d lost my wits, and sat heavily in one of the kitchen’s upright wooden chairs, her hand splayed between her breasts as if to keep her heart in. I poured her a stiff scotch, then one for myself. My hands and face still hurt like hell, but the pain was ebbing. Somewhere I’d trodden on something sharp with my shoeless foot; focusing on the chore of cleaning and dressing that wound helped me tune out, or at least turn the volume down on, some of the far worse things that had happened.

I found myself wondering if I were living in some comforting delusion, if suddenly her skin would start blistering and blackening and peeling away from her bones…

Although I remembered clearly that Riane and I had gone together to fetch a can of gas, it seemed that this wasn’t what happened at all. She’d felt drowsy after our pub lunch, so had decided to take a nap. The next she knew of me was when I was clamoring at the front door.

One thing she knew for certain was that my tales of time travel were impossible. She had no memory of those occasions she’d come with me. When I asked her where she’d thought the gas for the cars was coming from, because we certainly weren’t buying it at the Shell, she grew sufficiently distressed by the contradiction between logic and her memory that I backed off.

“But time travel just cannot be done!” she kept repeating, eyes full of tears.

As she’d told me a couple of days—or a lifetime—ago, both her own and Mary Cranston’s models of time’s workings rely on the notion that there’s a disconnect between past and future: there’s a probabilistic symmetry around the one fixed point of certainty, the Now. Riane’s death decades before she was born couldn’t affect, except in the most trivial way—an afternoon nap rather than a shared excursion—what happened in the present.

I don’t know why the portal took us back to a different day, just that once. Or maybe it wasn’t a different day—maybe it was the right day but in a rogue timeline. I never tried to go back to Two-Stroke Toilets again, so I had no way of telling. Paying full rate for a tank of gas seemed cheap—even at British prices—if it meant I never had to risk reliving that horror.

But the worst thing I didn’t know was if the “now” I’d come home to was the same “now” from which I’d departed. If the universe really does consist of an infinite array of parallel realities, are there other realities out there where Riane did in fact accompany me, and in which her death was permanent? It’s surely just as likely an outcome.

For the first few weeks afterwards, it looked as if everything would work out all right between us. I took my nerves and agitation to Dr. Wallen, who insisted I undergo a course of counselling; however, since I couldn’t tell the shrink—a Bovey Tracey man—the truth of what had happened, the effort was wasted. Even so, the nightmares started to be less soul-racking and to come less often.

But, as my mind became calmer, my unease at being around Riane increased. I found myself more and more often looking sidelong at her and wondering if I were living in the middle of some comforting delusion, if suddenly the picture would change and her skin would start blistering and blackening and peeling away from her bones…

I had new nightmares to replace the old ones, and far too often they were attacking me during the day, during my waking hours. I couldn’t make love to Riane, in case she disintegrated in my arms. I couldn’t even hold her. I began sleeping on the living-room couch. I couldn’t watch her eat.

Finally I left her a message telling her that this was no use, that we had to live apart, that the quirks of time might have saved her life but they’d nevertheless taken pains to ensure that, one way or the other, I lost my wife.

I think in the end it was a relief for her to see me go. Her nutty screenwriter husband.

It’s still good to hear her voice on the phone and know she’s alive and happy. There’s a new guy in the picture now, although she’s not entirely convinced he’s a keeper. Her work gets steadily more absorbing to her, steadily more incomprehensible to me. She tells me her students seem to get stupider every year but, thank mercy, there’s always a few brightly burning candles among them.

Me, all I have is the memory of Riane. Between phone calls, I never can decide if she’s alive or dead. If I went to visit her I’d know for sure, like opening the box on Schrödinger’s cat, but this is something I’m not going to do.

I lack the courage.

One last thing I did before leaving Tarburton was to go down to Nettie’s grocery store to give her back the key.

“It’s not my key,” she said sourly. The news was all over town that Riane and I were splitting up, and sympathy was heavily on Riane’s side. Everyone knew as a stone-cold fact that I was running off with some floozy actress half my age whom I’d impregnated in a drunken, dope-fueled orgy in Oxford, everyone knows how these television people are, morals of alley cats the lot of them. “You bought it yourself from Biggsie.”

“But I won’t be needing it any longer, Nettie. Take it. You can give it to someone else. Save them the expense of having their own copy made.”

Her cheeks seemed to warm a little at the prospect of doing Biggsie out of a sale. With a show of reluctance she spirited it away to some hidden compartment under the drawer of the till.

“One more thing,” I dared to say, now that we were almost friends again.

I flattened out one of the store’s paper bags on the counter.

L.A. MANGENS

General Stores

Fish and Game to Order

“Your name’s not just Nettie, is it?” I said.

She grunted. She hadn’t called on one of her beefy sons or grandsons to throw me out.

“You’re Linnet, aren’t you? That’s you out at the gas station—the garage, I mean. That’s why you’re just about the only person in Tarburton who never goes there.”

For a moment she looked over towards the far corner of the store as if gazing back over a vista of decades. Then she turned her piercing scrutiny in my direction once more.

“Have a good life, Mr. Duggan,” she said. “Wherever that life may lead you.”

John Grant is the author of some 70 books and the recipient of two Hugo Awards, a World Fantasy Award, and various others. His A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Film Noir was published last fall; he’s currently putting the final touches to The Young Person’s Guide to Bullshit for fall 2014 publication. He writes about movies regularly at Noirish.