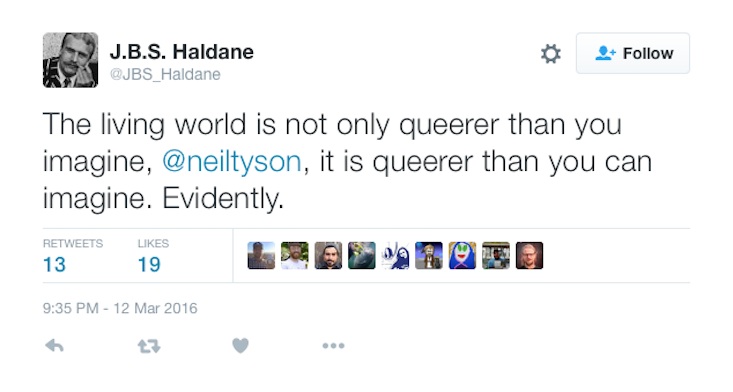

On Saturday afternoon, while I really should have been working on other things, this happened:

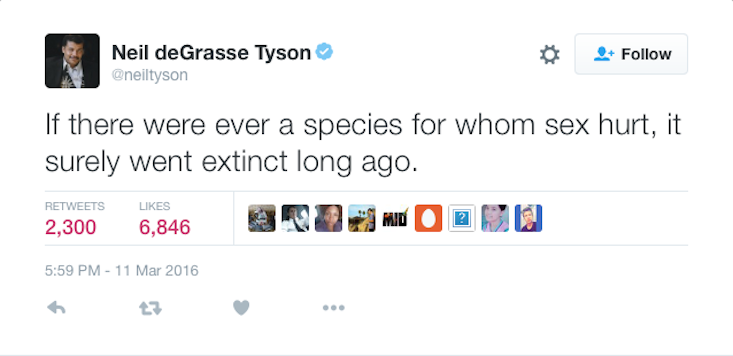

What’s going on here? It might be obvious if you have a background in biology, but there’s a lot of context, and science, behind that tweet. It all started last Friday, when astrophysicist and popular science personality Neil deGrasse Tyson tweeted:

This is actually false on its face, since there are lots of species for whom sex is painful, or at least it looks like it must be. Tyson’s responses and @-mentions filled up with biologists and science communicators pointing out spiny penises, traumatic insemination, and other ways that animal mating systems get kinky. A spoof hashtag, #BiologistSpaceFacts, encouraged biologists to turn the tables on Tyson by tweeting (deliberately, hilariously) uninformed descriptions of astronomical phenomena. All of which is to say, it was a pretty fun Friday on Science Twitter.

Then, Saturday, Tyson teed up for another go:

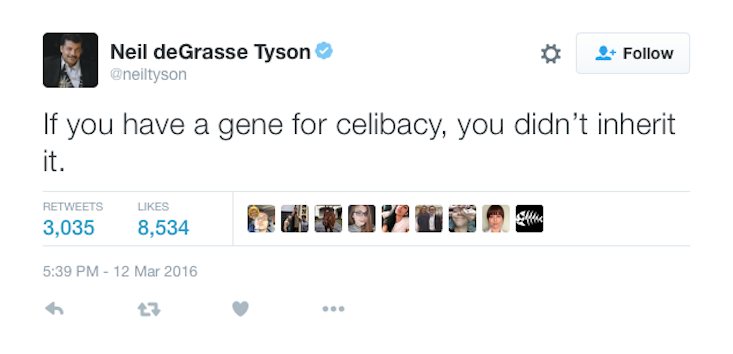

And he tweeted:

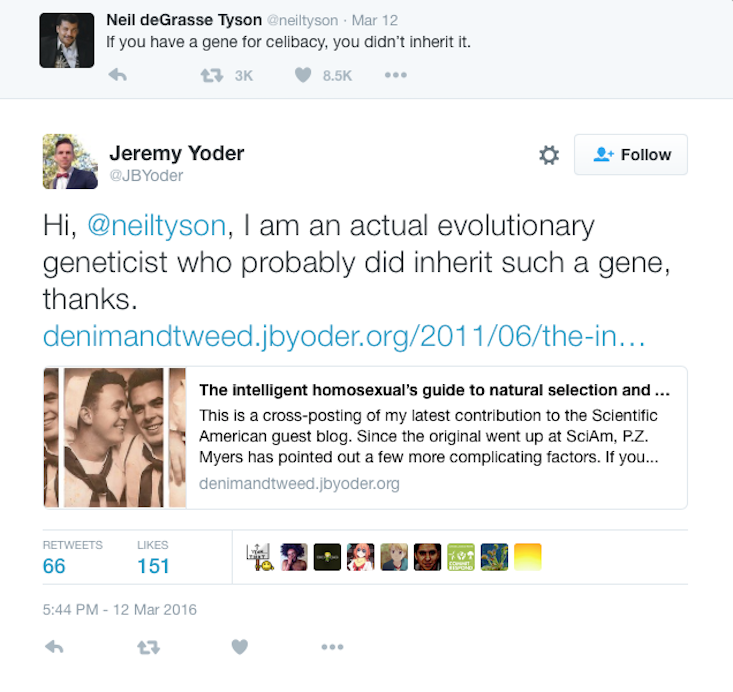

There was much renewed face-palming. Some folks objected to this usage of the word “gene,” which is more usually used to refer to a single location in the genetic code—the more precise wording would be “an allele for celibacy,” or “a gene variant for celibacy.” Real hard-core pedants pointed out that it’s not strictly right to say a gene is “for” anything. These objections are really not such a big deal, though, compared to the confusion inherent in the rest of the tweet.

Because there are, of course, social species with non-reproductive workers, whose non-reproductive status is ultimately determined by, yes, their genes. And gene variants that prevent reproduction can be recessive, so that they can, indeed, be inherited, and only have their deleterious effect manifest in individuals who inherit them from both parents. (In fact, basic evolutionary theory predicts that most gene variants with this kind of effect will be recessive.) It may be that there are multiple genes involved in “celibacy,” in which case an individual will only be celibate if he or she inherits the right variant for most or all of them. And if we’re talking about humans, it might be that a gene variant, which causes celibacy in one cultural context, doesn’t do so in others.

All of these factors come together nicely in a topic which is near and dear to my heart, and about which I’ve written a fair bit: the evolutionary context of human sexual orientation. Gene variants that, for instance, make men more likely to be gay, can persist in the population if they’re recessive, or if they have small individual effects, or if they don’t have similar effects when carried by women. It’s also possible that the cultural context in which they’re carried has a big impact—in some societies, men who might identify as gay in the U.S. or other Western cultures may stay at home and help their close relatives raise children, which could offset the selective effect of their own disinterest in reproductive sex. Or, in cultures less tolerant of homosexuality, many men who would otherwise identify as gay may marry and raise families because of social pressure.

That being said, Tyson’s “celibacy gene” tweet does actually express a very specific, and fascinating, population-genetic hypothesis: A gene variant that has sufficiently strong deleterious effects, one that is not recessive, can only exist in the population as a brand new mutation. If the gene variant would completely prevent the person carrying it from reproducing, or surviving to reproductive age, it could only be acquired by a person in one of two ways. First, it could be a mutation occurring in the cells that produced their parents’ eggs and sperm, which wouldn’t affect their parents’ health, but could be passed to the next generation. Second, it could be a mutation that occurred early in embryonic development, since mutations can and do occur in the many mitosis events involved in building an independent organism from a fertilized egg.

Geneticists can identify gene variants with strong deleterious effects by comparing human genome sequences to find regions where everyone has exactly the same sequence—places where any mutation would be immediately lethal. A non-recessive gene variant for “celibacy,” which wouldn’t be lethal but would (one way or another) prevent reproduction, wouldn’t be completely absent from a big sample of sequenced human genomes; but it should be very rare, and mostly present in the population because it has been continually reintroduced by mutation. In the subset of cases when those mutations occurred after fertilization, it’d be fair to say that, indeed, the “gene” for celibacy wasn’t inherited.

These are things we can look for, given the right kind of data—which is getting cheaper to obtain all the time. But all of this is the kind of nuance—and cool science—lost in a flippant tweet about a cartoonish understanding of natural selection.

Some folks have suggested, as the dust settles on this second round of “Neil deGrasse Tyson trolls all of biology,” that the response to Tyson has been disproportionate and not very helpful. But given Tyson’s enormous audience, and the fact that he’s specifically known for his pickiness about astronomical accuracy—remember that time he complained about the constellations in the sky for the climactic scene of Titanic?—I think he, of all people, could stand to be a little more self-aware about stepping outside his expertise. The tone of most of the responses I’ve seen to Tyson—certainly the tone I tried to aim for—ranged from jovial to disappointed. I don’t dislike Tyson as a result of all this—quite the contrary, I think he’s been one of our better science-popularizers, particularly in recent years. But precisely because I respect him, I expect him to do better.

As an endnote, for more on why an astrophysicist, particularly, might be prone to disregard details outside his own field of expertise, Cheryl Rofer, a chemist and an expert in chemical weapons destruction, has posted some enlightening and even-handed thoughts.

Jeremy Yoder is a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Plant Biology at the University of Minnesota. He also blogs at Denim and Tweed and Nothing in Biology Makes Sense!, and tweets under the handle @jbyoder.

This post, from The Molecular Ecologist, was reprinted with permission from Jeremy Yoder.