Every emotion has a purpose—an evolutionary benefit,” says Sandi Mann, a psychologist and the author of The Upside of Downtime: Why Boredom Is Good. “I wanted to know why we have this emotion of boredom, which seems like such a negative, pointless emotion.”

That’s how Mann got started in her specialty: boredom. While researching emotions in the workplace in the 1990s, she discovered the second most commonly suppressed emotion after anger was—you guessed it—boredom. “It gets such bad press,” she said. “Almost everything seems to be blamed on boredom.”

As Mann dived into the topic of boredom, she found that it was actually “very interesting.” It’s certainly not pointless. Wijnand van Tilburg from the University of Southampton explained the important evolutionary function of that uneasy, awful feeling this way: “Boredom makes people keen to engage in activities that they find more meaningful than those at hand.”

“Imagine a world where we didn’t get bored,” Mann said. “We’d be perpetually excited by everything—raindrops falling, the cornflakes at breakfast time.” Once past boredom’s evolutionary purpose, Mann became curious about whether there might be benefits beyond its contribution to survival. “Instinctively,” she said, “I felt that we all need a little boredom in our lives.”

Mann devised an experiment wherein a group of participants was given the most boring assignment she could think of: copying, by hand, phone numbers from the phone book. (For some of you who might never have seen one of those, Google it.) This was based on a classic creativity test developed in 1967 by J.P. Guilford, an American psychologist and one of the first researchers to study creativity. Guilford’s original Alternative Uses Test gave subjects two minutes to come up with as many uses as they could think of for everyday objects such as cups, paper clips, or a chair. In Mann’s version, she preceded the creativity test with 20 minutes of a meaningless task: in this case, copying numbers out of the phone book. Afterward, her subjects were asked to come up with as many uses as they could for two paper cups (the kind you get at an ecologically unscrupulous water cooler). The participants devised mildly original ideas for their cups, such as plant pots and sandbox toys.

When we space out, our minds aren’t switched off.

In the next experiment, Mann ratcheted up the boring quotient. Instead of copying numbers out of the phone book for 20 minutes, this time they had to read the phone numbers out loud. Although a handful of people actually enjoyed this task (go figure) and were excused from the study, the vast majority of participants found reading the phone book absolutely, stultifyingly boring. It’s more difficult to space out when engaged in an active task such as writing than when doing something as passive as reading. The result, as Mann had hypothesized, was even more creative ideas for the paper cups, including earrings, telephones, all kinds of musical instruments, and, Mann’s favorite, a Madonna-style bra. This group thought beyond the cup-as-container.

By means of these experiments, Mann proved her point: People who are bored think more creatively than those who aren’t.

But what exactly happens when you get bored that ignites your imagination? “When we’re bored, we’re searching for something to stimulate us that we can’t find in our immediate surroundings,” Mann explained. “So we might try to find that stimulation by our minds wandering and going to someplace in our heads. That is what can stimulate creativity, because once you start daydreaming and allow your mind to wander, you start thinking beyond the conscious and into the subconscious. This process allows different connections to take place. It’s really awesome.” Totally awesome.

Boredom is the gateway to mind-wandering, which helps our brains create those new connections that can solve anything from planning dinner to a breakthrough in combating global warming. Researchers have only recently begun to understand the phenomenon of mind-wandering, the activity our brains engage in when we’re doing something boring, or doing nothing at all. Most of the studies on the neuroscience of daydreaming have only been done within the past 10 years. With modern brain-imaging technology, discoveries are emerging every day about what our brains are doing not only when we are deeply engaged in an activity but also when we space out.

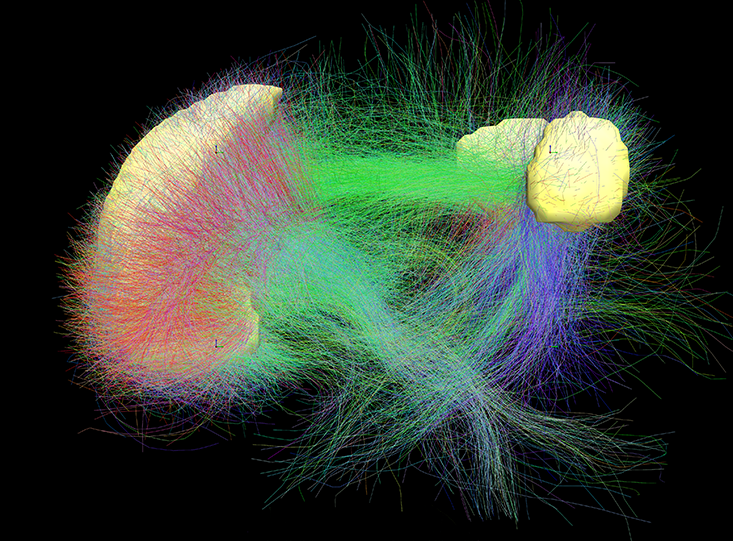

When we’re consciously doing things—even writing down numbers in a phone book—we’re using the “executive attention network,” the parts of the brain that control and inhibit our attention. As neuroscientist Marcus Raichle put it, “The attention network makes it possible for us to relate directly to the world around us, i.e., here and now.” By contrast, when our minds wander, we activate a part of our brain called the “default mode network,” which was discovered by Raichle. The default mode, a term also coined by Raichle, is used to describe the brain “at rest”; that is, when we’re not focused on an external, goal-oriented task. So, contrary to the popular view, when we space out, our minds aren’t switched off.

“Scientifically, daydreaming is an interesting phenomenon because it speaks to the capacity that people have to create thought in a pure way rather than thought happening when it’s a response to events in the outside world,” said Jonathan Smallwood, who has studied mind-wandering since the beginning of his career in neuroscience, 20 years ago. (Perhaps not coincidentally, the year he finished his Ph.D. was the same year the default mode was discovered.)

“Imagine a world where we didn’t get bored. We’d be perpetually excited by everything—raindrops falling, the cornflakes at breakfast time.”

Smallwood—who is so enamored with mind-wandering, it’s his Twitter handle—explained why his discipline is still in its infancy. “It has an interesting place in the history of psychology and neuroscience simply because of the way cognitive science is organized,” he said. “Most experimental paradigms and theories tend to involve us showing something to the brain or the mind and watching what happens.” For most of the past, this task-driven method has been used to figure out how the brain functions, and it has produced a tremendous amount of knowledge regarding how we adapt to external stimuli. “Mind-wandering is special because it doesn’t fit into that phenomenon,” Smallwood said.

We’re at a pivotal point in the history of neuroscience, according to Smallwood, because, with the advent of brain imaging and other comprehensive tools for figuring out what’s going on in there, we are beginning to understand functioning that has until now escaped study. And that includes what we experience when we’re off-task or, no pun intended, in our own heads.

The crucial nature of daydreaming became obvious to Smallwood almost as soon as he began to study it. Spacing out is so important to us as a species that “it could be at the crux of what makes humans different from less complicated animals.” It is involved in a wide variety of skills, from creativity to projecting into the future.

There is still so much to discover in the field, but what’s definitely clear is that the default mode is not a state where the brain is inactive. Smallwood uses functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to explore what neural changes occur when test subjects lie in a scanner and do nothing but stare at a fixed image.

It turns out that in the default mode, we’re still tapping about 95 percent of the energy we use when our brains are engaged in hardcore, focused thinking. Despite being in an inattentive state, our brains are still doing a remarkable amount of work. While people were lying in scanners in Smallwood’s experiment, their brains continued to “exhibit very organized spontaneous activity.”

“We don’t really understand why it’s doing it,” he said. “When you’re given nothing to do, your thoughts don’t stop. You continue to generate thought even when there’s nothing for you to do with the thoughts.”

Part of what Smallwood and his team are working on is trying to connect this state of unconstrained self-generated thought and that of organized, spontaneous brain activity, because they see the two states as “different sides of the same coin.”

People who are bored think more creatively.

The areas of the brain that make up the default mode network—the medial temporal lobe, the medial prefrontal cortex, and the posterior cingulate cortex—are turned off when we engage in attention-demanding tasks. But they are very active in autobiographical memory (our personal archive of life experiences); theory of mind (essentially, our ability to imagine what others are thinking and feeling); and—this one’s a doozy—self-referential processing (basically, crafting a coherent sense of self).

When we lose focus on the outside world and drift inward, we’re not shutting down. We’re tapping into a vast trove of memories, imagining future possibilities, dissecting our interactions with other people, and reflecting on who we are. It feels like we are wasting time when we wait for the longest red light in the world to turn green, but the brain is putting ideas and events into perspective.

This gets to the heart of why mind-wandering or daydreaming is different from other forms of cognition. Rather than experiencing, organizing, and understanding things based on how they come to us from the outside world, we do it from within our own cognitive system. That allows for reflection and the ability for greater understanding after the heat of the moment. Smallwood gives the example of an argument: While it’s happening, it’s hard to be objective or see things from the perspective of the other person. Anger and adrenaline, as well as the physical and emotional presence of another human being, get in the way of contemplation. But in the shower or on a drive the next day, when your brain relives the argument, your thoughts become more nuanced. You not only think of a million things you should have said, but, perhaps, without the “stimulus that is the person you were arguing with,” you might get another perspective and gain insights. Thinking in a different way about a personal interaction, rather than the way you did when you encountered it in the real world, is a profound form of creativity spurred on by mind-wandering.

“Daydreaming is especially crucial for a species like ours, where social interactions are important,” Smallwood said. “That’s because in day-to-day life, the most unpredictable things you encounter are other people.” If you break it down, most of our world, from traffic lights to grocery store checkouts, is actually governed by very simple sets of rules. People—not so much. “Daydreaming reflects the need to make sense of complicated aspects of life, which is almost always other human beings.”

Talking to Professor Smallwood had me more convinced than ever that it’s destructive to fill all the cracks in our day with checking e-mail, updating Twitter, or incessantly patting our pockets or bag to check for a vibrating phone. I saw why letting one’s mind wander really is the key to creativity and productivity.

“Well, that’s a contentious statement,” Smallwood said. “I mean, people whose minds wander all the time wouldn’t get anything done.”

Fair point. I didn’t like that Smallwood was trying to slow me down, but, true enough, daydreaming hasn’t always been considered a good thing. Freud thought daydreamers were neurotic. As late as the 1960s, teachers were warned that daydreaming students were at risk for mental health issues.

There are obviously different ways to daydream or mind-wander—and not all of them are productive or positive. In his seminal book The Inner World of Daydreaming, psychologist Jerome L. Singer, who has been studying mind-wandering for more than 50 years, identifies three different styles of daydreaming:

• poor attention control

• guilty-dysphoric

• positive-constructive

And, yes, they are just what they sound like. People with poor attention control are anxious, easily distracted, and have difficulty concentrating, even on their daydreams. When our mind-wandering is dysphoric, our thoughts drift to unproductive and negative places. We berate ourselves for having forgotten an important birthday or obsess over failing to come up with a clever retort when we needed one. We’re flooded with emotions like guilt, anxiety, and anger. For some of us, it’s easy to get trapped in this cycle of negative thinking. Not surprisingly, this kind of mind-wandering is more frequent in people who report chronic levels of unhappiness. When dysphoric mind-wandering becomes chronic, it can lead people into destructive behaviors like compulsive gambling, addiction, and eating disorders. The question, however, is whether mind-wandering is not only more frequent in people who report chronic levels of unhappiness, but whether it also promotes unhappiness. In a 2010 study called “A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind” (gulp), Harvard psychologists Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert developed an iPhone app to survey the thoughts, feelings, and actions of 5,000 people at any given time throughout a day. (When a chime went off randomly on the participant’s smart-phone, up popped a series of questions that touched on what the person was doing, if he was thinking about what he was doing, and how happy he was, among other things.) From the results of the survey, Killingsworth and Gilbert found that “people are thinking about what is not happening almost as often as they are thinking about what is” and “doing so typically makes them unhappy.”

It’s just like what you hear in every yoga class—the key to happiness is being in the moment. So what’s the deal? Is mind-wandering productive or self-defeating? Well, it seems that, like everything else in life, daydreaming is complicated.

Smallwood coauthored a study on the relationship between mood and mind-wandering that found “the generation of thoughts unrelated to the current environment may be both a cause and a consequence of unhappiness.” What!?

Spacing out is so important to us as a species that “it could be at the crux of what makes humans different from less complicated animals.”

The 2013 study (coauthored by Florence J.M. Ruby, Haakon Engen, and Tania Singer) argues that not all kinds of self-generated thought or mind-wandering are alike. The data collected from approximately 100 participants took into account whether their thoughts were task related, focused on the past or future, about themselves or others, and positive or negative. What this study found was that, yes, negative thoughts brought about negative moods (no duh). Self-generated thought in depressed people tended to cause and be caused by negative moods, and “past-related thought may be especially likely to be associated with low mood.” But all hope is not lost. The study also found that “by contrast, future- and self-related thoughts preceded improvements of mood, even when current thought content was negative.”

“Daydreaming has aspects that will allow us to think originally about our lives,” Smallwood told me. “But in certain circumstances, continuing to think about something might not be the right thing to do. Many states of chronic unhappiness are probably linked to daydreaming simply because there are unsolvable problems.”

Mind-wandering is not unlike our smartphones, where you can easily have too much of a good thing. Smallwood argues that we shouldn’t think about the technology of our phones—or our brains—in terms of the value judgments “good” or “bad.” Rather it comes down to how we put them to use. “Smartphones allow us to do all kinds of amazing things like contact people from great distances, but we can get trapped in devoting our entire life to them,” he said. “That’s not the smartphone’s fault.” Daydreaming gets us to think about things in a different way, for good, bad, or, well, just different.

The flip side of dysphoric daydreaming, the positive-constructive kind, is when our thoughts veer toward the imaginative. We get excited about the possibilities that our brain can conjure up seemingly out of nowhere, like magic. This mode of mind-wandering reflects our internal drive to explore ideas and feelings, make plans, and problem-solve.

So how can we engage in healthy mind-wandering? Let’s say you had a tiff with your coworker. That night, while making a salad, you find yourself replaying the scene over and over in your mind; waves of anger wash over you yet again as you berate yourself for not having come up with a wittier retort to his underhanded comment implying you hadn’t pulled your weight during a recent project. But with positive-constructive mind-wandering, you’d get over the past and come up with a way to show him all the legwork these projects require of you … or maybe you resolve to be put on another team altogether and avoid the jerk entirely because life’s too short.

“It’s easier said than done to change your thinking,” Smallwood said. “Daydreaming is different from many other forms of distraction in that when your thoughts wander to topics, they’re telling you something about where your life is and how you feel about where it is. The problem with that is sometimes when people’s lives aren’t going so well, daydreaming might feel more difficult than it would be at times when their lives are going great. Either way, the point is that it does provide insight into who we are.”

All those hours I spent as a new mother, pushing my colicky baby in a stroller because he wouldn’t sleep any other way and wishing I could be more productive or in touch with what was going on in the rest of society, were actually incredibly useful, because I had unwittingly been letting my mind have space and time to travel much further than ever before. I not only tapped into past experiences but also imagined myself in future places of my own design, doing autobiographical planning. While ruminating on painful experiences or dwelling on the past is definitely a very real by-product of daydreaming, research by Smallwood and others has shown that, when given time for self-reflection, most people tend toward “prospective bias.” That kind of thinking helps us come up with new solutions—like, in my case, a whole new career. By design, daydreaming is helpful to us when we’re stuck on a problem, personal, professional, or otherwise. And boredom is one of the best catalysts to kick-start the process.

At first glance, boredom and brilliance are completely at odds with each other. Boredom, if defined just as the state of being weary and restless through lack of interest, overwhelmingly has negative connotations and should be avoided at all costs, whereas brilliance is something we aspire to—a quality of striking success and unusual mental ability. Genius, intellect, talent, air versus languidness, dullness, doldrums. It’s not immediately apparent, but these two opposing states are in fact intimately connected.

Andreas Elpidorou, a researcher in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Louisville and self-described defender of boredom, explains, “Boredom motivates the pursuit of a new goal when the current goal ceases to be satisfactory, attractive, or meaningful [to you].” In his 2014 academic article “The Bright Side of Boredom,” Elpidorou argues that boredom “acts as a regulatory state that keeps one in line with one’s projects. In the absence of boredom, one would remain trapped in unfulfilling situations and miss out on many emotionally, cognitively, and socially rewarding experiences. Boredom is both a warning that we are not doing what we want to be doing and a ‘push’ that motivates us to switch goals and projects.”

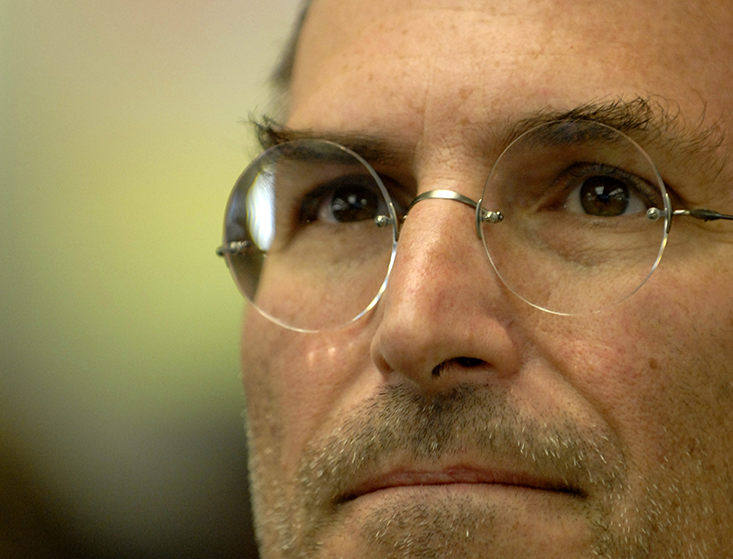

You could say that boredom is an incubator lab for brilliance. It’s the messy, uncomfortable, confusing, frustrating place one has to occupy for a while before finally coming up with the winning equation or formula. This narrative has been repeated many, many times. The Hobbit was conceived when J.R.R. Tolkien, a professor at Oxford, “got an enormous pile of exam papers there and was marking school examinations in the summer time, which was very laborious, and unfortunately also boring.” When he came upon one exam page a student had left blank, he was overjoyed. “Glorious! Nothing to read,” Tolkien told the BBC in 1968. “So I scribbled on it, I can’t think why, ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.’” And so, the opening line of one of the most beloved works of fantasy fiction was born. Steve Jobs, who changed the world with his popular vision of technology, famously said, “I’m a big believer in boredom. … All the [technology] stuff is wonderful, but having nothing to do can be wonderful, too.” In a Wired piece by Steven Levy, the cofounder of Apple—nostalgic for the long, boring summers of his youth that stoked his curiosity because “out of curiosity comes everything”—expressed concern about the erosion of boredom from the kind of devices he helped create.

When it came to brilliance, Steve Jobs was the master. So let’s take him up on his advice to embrace boredom. Let your knowledge of the science and history behind boredom inspire you to bring it back into your life. You might feel uncomfortable, annoyed, or even angry at first, but who knows what you can accomplish once you get through the first phases of boredom and start triggering some of its amazing side effects?

Manoush Zomorodi is the host and managing editor of “Note to Self,” “the tech show about being human,” from WNYC Studios. Every week on her podcast, Manoush searches for answers to life’s digital quandaries through experiments and conversations with listeners and experts. She has won numerous awards for her work including four from the New York Press Club. Manoush is the author of Bored and Brilliant and Camera Ready.

From Bored and Brilliant by Manoush Zomorodi. Copyright © 2017 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Lead photo credit: Bezikus / Shutterstock