Darcie Moore is an expert on cargo. Not the kind you’d find on a freight train, though—it’s the cargo you’d find in stem cells, the kind that can transform into the different types of cells your body needs in your brain, skin, hair follicles, and lots of other places. They’re especially critical when we’re developing at an early age, but adults have them, too.

As stem cells grow and replicate, they can accumulate misfolded proteins and other gunk—“cargo”—that harms their function by, in Moore’s words, “exhausting” them. Nautilus caught up with Moore, a neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, to talk about how she investigates stem cell exhaustion and how it contributes to the puzzle of aging.

What do stem cells have to do with aging?

The theory is that during aging, your stem cells begin to dysfunction. For example, you begin to lose the ability to make pigment in your hair with aging due to melanocyte stem cells becoming depleted. Some of the concepts that apply to stem cell aging have been initially studied quite a bit in yeast, including the work my lab does, and it’s only recently that this work has started to take off in mammalian systems.

Why study yeast aging?

Every time these unicellular organisms divide, they’re aging based on the number of cell divisions, and not necessarily on chronological age. Scientists researching yeast have found a barrier that limits the movement of proteins between the mother and their bud. We thought this might be really interesting to explore in neural stem cells of the brain, to see if replicative aging occurred there.

With the different hallmarks of aging, often people ask, “What comes first?”

Did you find something similar happening in cells like ours?

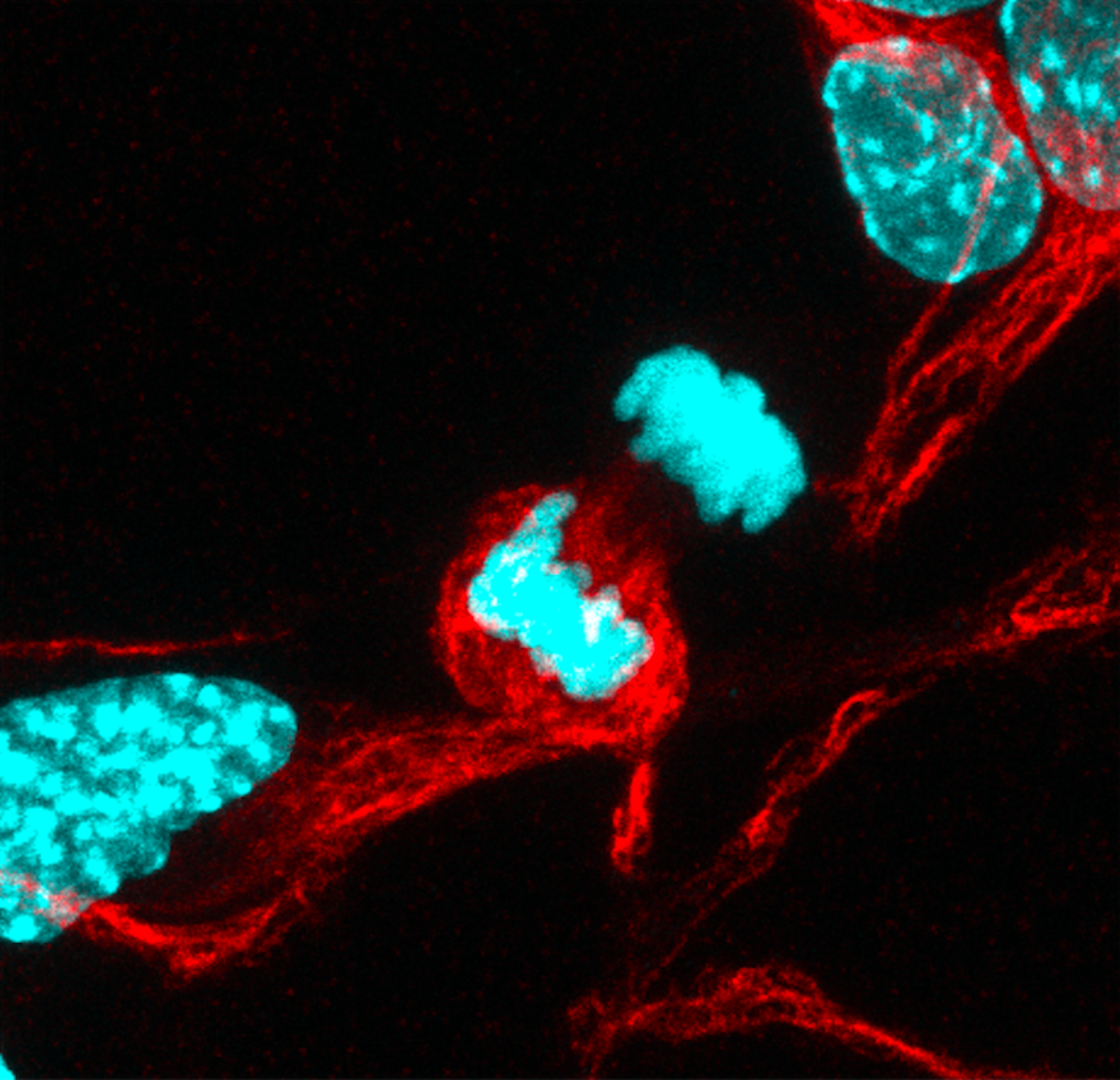

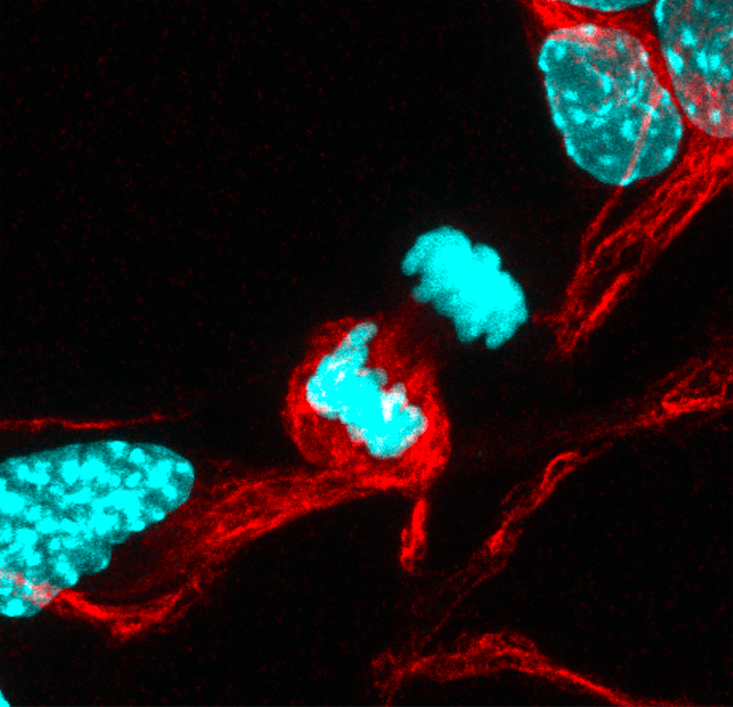

We did find that our neural stem cells also had a barrier. We also found that, similar to yeast, when neural stem cells divide, they can segregate some cargoes that are inside [the cell] and give them specifically to one of their two daughter cells. If we saw that that barrier was strong (less movement between the two daughter cells), we also saw more cargo asymmetry. One cell is sacrificed to inherit the “garbage,” and that allows the other cell to still function well, to rejuvenate the population.

How does stem cell replication fit into the larger puzzle of aging?

We think that stem cell dysfunction occurs at least partially due to the loss of the ability of stem cells to asymmetrically segregate these cargoes during division between their two daughter cells to rejuvenate their populations. With aging, the neural stem cells divide and separate these negative cargoes equally to each of the two daughter cells, resulting in both daughter cells beginning to dysfunction. It’s still a correlation and not a direct relationship, but it does appear that the barrier could potentially be important, maybe in a passive way, for maintaining this separation. When that barrier was leaky between the two cells, then we saw more symmetric distribution of these cargoes, as in the old cells.

Where is aging research headed?

With the different hallmarks of aging, often people ask, “What comes first?” DNA damage, shortened telomeres, loss of protein quality control, epigenetic changes and more, all occur during aging. There is also stem cell exhaustion or dysfunction. I think what most people are focused on in their research, though, is trying to increase healthspan—the length of time we are healthy. Because, if you look at the numbers, lifespan has increased, but not healthspan. So we are sicker for longer. Besides the normal concerns with cost and burden, I know for myself, I don’t want to increase the time I live only to be miserable for longer.

Dan Garisto is an editorial intern at Nautilus.

WATCH: There has always been an enormous lunatic fringe around aging.

Hayflick%u2019s ideas have revolutionized the way we think about aging: as a process intrinsic to our cells, and not the result of outside stressors.” data-credits=”” style=“width:733px”>

Hayflick%u2019s ideas have revolutionized the way we think about aging: as a process intrinsic to our cells, and not the result of outside stressors.” data-credits=”” style=“width:733px”>

This article was originally published on Nautilus Aging in December 2017.