For weeks, Adam Smith had been crunching the raw data from more bird statistics than anyone had ever tried before—thirteen different bird counts and millions of radar sweeps. Suddenly he heard the musical chime that tells him his results are ready. He leaned across his desk, surrounded by enough high-powered computers to heat up his entire office, and stared at what could only be an impossible conclusion: Over the past fifty years, his calculations found, a third of North America’s birds had vanished. “Well, that can’t be right,” he thought. “I must have made a mistake somewhere.”

Smith, one of the hemisphere’s top specialists in bird populations, just sat for a while in his cluttered cubicle at the Canadian Wildlife Service, which was decorated with caribou antlers, a musk-ox skull, and early drawings from his twin boys. Then it dawned on him. “This would be a massive change, an absolutely profound change in the natural system,” he said. “And we weren’t even aware of it.”

Up until that point, counting the abundance of individual birds throughout the entire continent was impossible. At any given time, many species number in the tens of millions in North America—adding up to billions of birds—and they’re constantly on the move. But the science of bird study was advancing, and a close-knit group of scientists was experimenting with using radar imagery, satellite photos, and citizen science to add precision to the dozens of conventional bird counts done for groups of species.

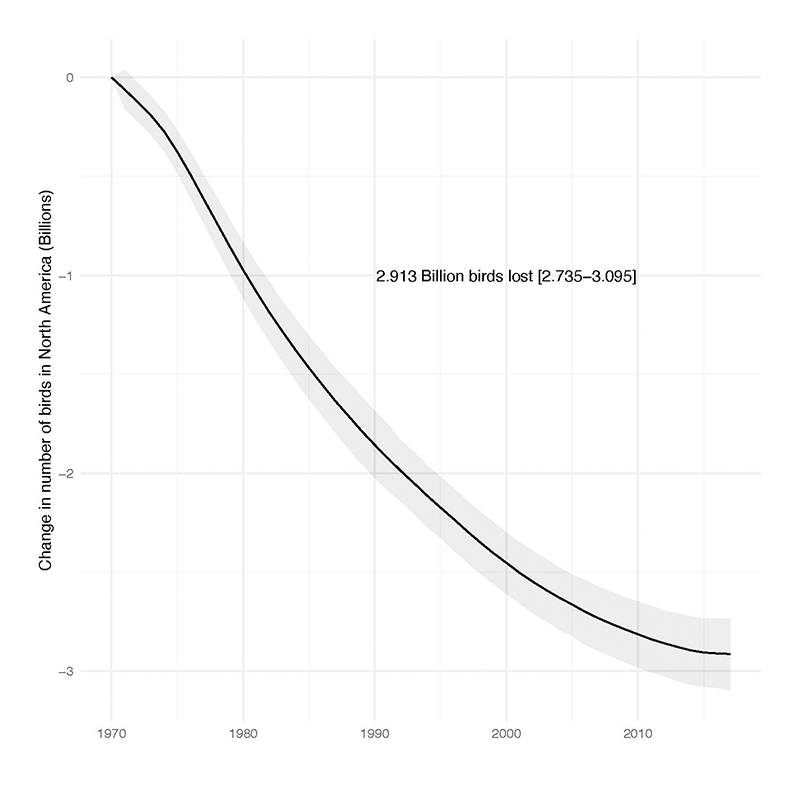

The computation Smith had just finished that day in May 2019 combined individual population estimates for 529 bird species, from the most common sparrows and robins to rarities hardly ever seen. When Smith pulled these estimates together and adjusted each for its degree of certainty, the findings came down to a single ski slope of a chart. It showed a precipitous drop in nearly all these species in every part of the continent. At the bottom sat four lone digits—2.913. That’s the number of breeding birds in billions that had disappeared since the early 1970s. He had documented an accelerating churn of seasonal losses that slowly took their toll on the abundance of birds. And it translated to an astounding third of the adult birds that not long ago filled North America but now are gone.

The hardest hit were grassland birds, down by more than 50 percent, mostly due to the expansion of farms that turn a varied landscape into acres of neat, plowed rows. That equates to 750 million birds, from bright yellow Eastern and Western Meadowlarks with their incessant morning songs to the stately Horned Lark with black masks across the male’s eyes and tiny hornlike feathers that sometimes stick up from their heads. Forest birds lost a third of their numbers, or 500 million, including the compact, colorful warblers and speckle-breasted Wood Thrushes that sing like flutes. Common backyard birds experienced a seismic decline. That’s where 90 percent of the total loss of abundance occurred, among just twelve families of the best-known birds—including sparrows, blackbirds, starlings, and finches. There’s been relatively little research on these species, and there’s no sense of urgency when resources are already stretched thin for so many other birds in more dire need.

The possibility of such losses was too startling to share with his colleagues until Smith checked every step of his calculations, particularly since he’d never attempted this analysis before. “It always takes a couple of times to get these numbers right,” he said. After a day and a half of painstaking scrutiny, Smith realized there was no mistake. “I was speechless. We’ve lost almost 30 percent of an entire class of organisms in less than the span of a human lifetime, and we didn’t know it.”

From A Wing and a Prayer: The Race to Save Our Vanishing Birds by Anders Gyllenhaal and Beverly Gyllenhaal. Copyright © 2023 by Anders Gyllenhaal and Beverly Gyllenhaal. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Lead image: Bonnie Taylor Barry / Shutterstock