Nothing prepared Nicole Stott for her first view of Earth from space. “I was overwhelmed,” she says. “I felt awe, and then this connection with gratitude to be looking at our glowing, colorful planet in deep space.”

Stott’s first spaceflight was in 2009 as a flight engineer on the NASA space shuttle to support a three-month International Space Station mission. At the start of that mission, she conducted a nearly seven-hour spacewalk to perform maintenance. “I’ll tell you, a spacewalk, that’s one of the times of my life where I felt the most alone and detached from any other human being,” Stott has said. “But at the same time, I also felt the closest and most connected to humanity.”

Philosophically, Stott says, her “Earthrise moment,” a reference to the 1968 photograph taken by astronaut Bill Ander of the Earth rising over the moon, “changed everything for me.” That experience “was what I wanted to carry back—the awesomeness of the whole idea that we live on a planet. I felt that we all needed to be in awe of the Earth that we’re surrounded by every day.”

We can cultivate a profound sense of being part of a vast crew on Earth.

After 27 years at NASA, Stott, 61, is now retired. In her 2021 book, Back to Earth, she writes that astronauts want to share the extraordinary perspective of the Earthrise moment because “we believe it has the power to raise everyone’s awareness of our role as crewmates here on Spaceship Earth.”

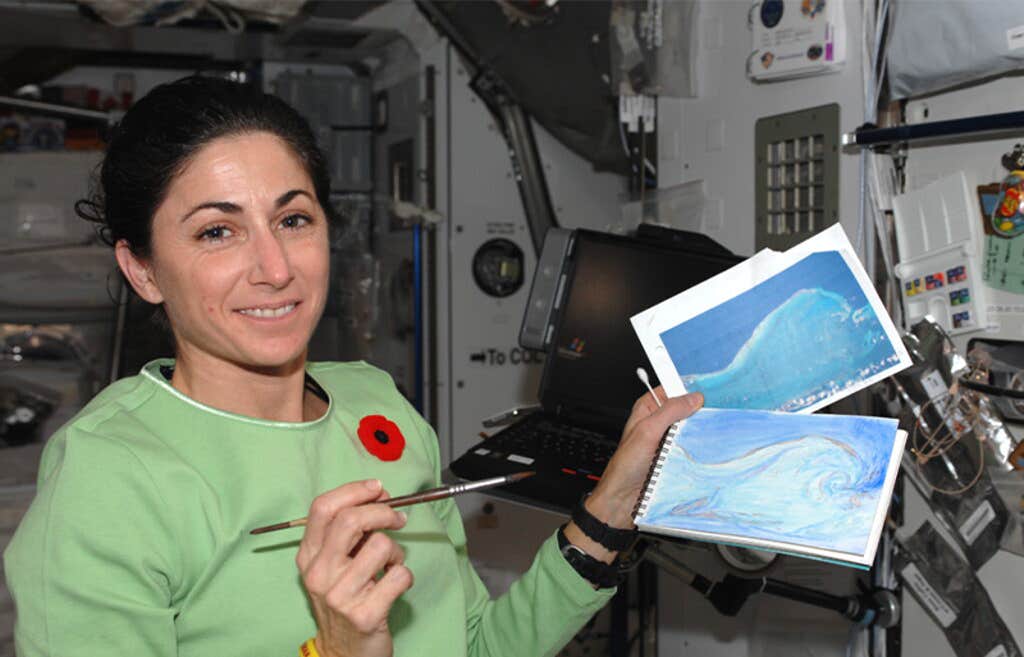

We met this past December in Miami. Stott was there on behalf of UNESCO and Nautilus for a fascinating conversation with ocean explorer Victor Vescovo at the Frost Science Museum about the similarities of their experiences in deep space and the deep ocean. Stott is an artist and is the first astronaut to paint with watercolors in space, a swirling of bluish waves from the heavens.

Stott and I recently spoke over Zoom about the insights she gained from her space experiences, including the value of plants and art in space, and how she continues to advocate for a more conscious and cooperative approach to addressing the challenges facing our planet.

How do the principles guiding space travel—and belief in finding solutions to complex problems—extend to Earth?

This perspective resonates universally. It revolves around the themes of hope and inspiration, centered on the conviction that solutions exist—and adopting an approach that explores the myriad ways problems can be solved, as opposed to dwelling on impediments.

This ethos, ingrained in the preparations and missions of astronauts, seamlessly aligns with life on Earth. It underscores the imperative for Earth’s inhabitants to emulate the spirit of a space crew, functioning as active participants rather than passive observers.

On Earth, cultivating a comprehensive understanding of the environment and all its life forms is crucial to determining how one can positively impact the world. This mirrors the daily activities aboard the space station, where every action, from scientific endeavors to constructing the station and managing its technology, is driven by the goal of fostering a positive influence. The routine involves assessing factors like atmospheric composition, clean water availability, structural integrity, and the well-being of fellow crewmates before delving into broader tasks for the day.

The smell of the plants deeply resonated aboard the sterile International Space Station.

This conscious effort to understand and contribute aligns with the concept of Earth’s inhabitants functioning as a collective crew. It underscores our innate ability to tackle intricate problems and position ourselves as active contributors to the solutions required for survival.

The shared belief that solutions exist is paramount, and it necessitates the proactive integration of varied skills and perspectives to implement these solutions effectively. In essence, acknowledging our capacity to overcome challenges and actively participating in the solution is a universal imperative that applies both in the vastness of space and the intricacies of life on Earth.

Did you and your fellow crew members undergo social training to mitigate friction and stress, fostering better teamwork? Moreover, is such training something that should be implemented on Earth?

Much of our approach in the human spaceflight community stems from the imperative to collaboratively solve challenges. It’s a deliberate effort rooted in the awareness that we will operate as a team in extreme and remote environments, where our dependence on one another is vital for daily survival. Our training reflects this reality, shaping the fabric of our lives in space.

Each challenge we encounter becomes a revealing journey, exposing individual strengths and weaknesses while fostering an acute awareness of these aspects within our crewmates.

Acknowledging personal weaknesses can be difficult. Yet, the success of our missions hinges on balancing individual strengths within the crew, and recognizing that diversity contributes to a more robust and effective team.

By embracing this ethos on Earth, we can cultivate a profound sense of being part of a vast crew, with each individual contributing uniquely to the collective solution for the benefit of all inhabitants of our planet.

In essence, every person, consciously or not, bears a mission on Earth. This journey entails the exploration and understanding of one’s strengths, learning how to harmonize them with others, and actively participating in the shared mission to ensure the well-being and prosperity of all life on our shared home.

You hold the distinction of being one of the first artists in space and notably the first person to bring watercolors into orbit. Could you share your experience of painting from the cosmos?

There’s a common misconception that astronauts are solely focused on the technical aspects of a mission and that the idea of engaging in art seems incongruous with their roles. However, I’ve found the opposite to be true, and it brings me immense joy. In tackling challenging problems, we discover that believing in solutions entails utilizing our entire brain—leveraging all our talents for creative problem-solving.

I was delighted to learn that many of my colleagues, including those involved in mission control and astronaut training, also had interests in art, music, poetry, or photography. This connection between humanity and artistic expression has been a constant thread throughout human spaceflight history. It’s a testament to our innate desire to carry our humanity with us wherever we go.

Regardless of our destination, humans will always seek ways to carry parts of Earth with us.

When I brought watercolors into space, the experience was unique due to the absence of gravity. Everything, including water and paintbrushes, floated. I encountered a learning curve in painting without gravity—dipping my brush into a floating ball of water and observing how water and paint behaved differently than on Earth.

Organization became crucial, as there were no stable surfaces. Every item had to be thoughtfully arranged, adding a new dimension to the artistic process. Additionally, I couldn’t simply float in front of a window and paint whatever caught my eye. Traveling at 17,500 miles per hour, or about five miles per second, meant that the scenery changed rapidly. To address this, I printed out a picture of a chain of islands off the northern coast of Venezuela and painted based on that image. Despite the challenges, it was a transformative experience, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to explore art in a space environment.

The ISS is a hyper-clean environment, but it has space for work with less-sterile experiments, like those with plants. Can you tell us about that and the meaning that plants take on in space?

Gardening is also a passion of mine, much like art, and it led me to want to work with plants during experiments on the space station.

The space station itself is enormous—a vast expanse where six or seven crew members can navigate independently during the day if they choose. It is a sterile environment with its white walls, cables, and unscented products designed to maintain clean air. But there exists a shared desire among us to come together and share experiences.

Whenever there were plant experiments, I always eagerly raised my hand. There’s an innate connection within us to be part of the nature from which we originated. Even working with tiny Arabidopsis (cress) flowers, resembling the tiniest version of baby’s breath, and related to cabbage and mustard plants, was a truly incredible experience. Opening the case, harvesting them, and experiencing the smell—a connection to Earth while on the space station—was profound.

If one of us was working on a plant experiment, we all wanted to be there to witness it. It was fascinating to see everyone’s eagerness to get a little sense of Earth, even though devoid of soil, the smell of the plants and even the nutrient mix had distinctive aromas that deeply resonated with us.

Growing plants in space presents numerous challenges, and, over time, space station plant experiments have evolved. Now we have greenhouse-like structures where crew members grow peppers, tomatoes, lettuce, and more. Although there was once a debate about whether crew members could consume their harvest, they can now open the plastic boxes, savor the scents, taste the plants, and revel in the harvest. It represents a connection back to Earth, and I believe that regardless of our destination, humans will always seek ways to carry Earth with us. The profound importance of the sensory aspects of the plant world adds a beautiful and remarkable dimension to the space story.

Moreover, cultivating plants in space serves as a valuable lesson in growing plants in challenging environments on Earth and advancing sustainability practices. Reflecting on my experiences back in my garden, there was nothing quite like putting my feet in the soil and feeling the profound connection to standing on the planet Earth. ![]()

This article is adapted from Plantings: The Journal of the World Sensorium/Conservancy.

Lead image courtesy of NASA.