I remember the day when, at the age of 7, I realized that I wanted to figure out how reality worked. My mother and father had just taken us shopping at a market in Calcutta. On the way back home, we passed through a dimly lit arcade where a sidewalk bookseller was displaying his collection of slim volumes. I spotted an enigmatic cover with a man looking through a microscope; the words “Famous Scientists” were emblazoned on it, and when I asked my parents to get it for me, they agreed. As I read the chapters, I learned about discoveries by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek of the world of microscopic life, by Marie Curie about radioactivity, by Albert Einstein about relativity, and I thought, “My God, I could do this, too!” By the time I was 8, I was convinced that everything could be explained, and that I, personally, was going to do it.

Nautilus premium members can listen to this story, ad-free.

Subscribe now to unlock Nautilus Narrations >

Nautilus members can listen to this story.

Subscribe now to unlock Nautilus Narrations >

Decades have passed, and I am now a theoretical physicist. My job is to work out how all of reality works, and I take that mission seriously, working on subjects ranging from the quantum theory of gravity to theoretical neuroscience. But I must confess to an increasing sense of uncertainty, even bafflement. I am no longer sure that working out what is “real” is possible, or that the reality that my 7-year-old self conceived of even exists, rather than being simply unknown. Perhaps reality is genuinely unknowable: Things exist and there is a truth about them, but we have no way of finding it out. Or perhaps the things we call “real” are called into being by their descriptions but do not independently exist.

The theories and concepts we build are like ladders we use to reach the truth.

I am steeped in the cultural traditions of physics, a field that is my calling and trade, and in the philosophies of India with which I was raised. As a physicist, I remain committed to a system of thought which posits that: (1) things we observe are definitely real, (2) the details may be unknown, (3) bounded resources may slow progress, but (4) physical inquiry can lead us to the real truth, as long as we have time and proceed with patience. On the other hand, I am also acutely aware of philosophical traditions to the effect that: (1) there may be a reality, but (2) measurements from the world are inherently misleading and partial, so that (3) the real may be formally indescribable, and that (4) we may not have a systematic way to reach the fundamentally real and true.

The idea that the real may be unknowable is very old. Consider the creation hymn in the Rig Veda, composed around 1500 to 1000 B.C., called the “Nasadiya Sukta.” This verse addresses fundamental questions of cosmology and the origin of the universe. In a beautiful translation by Juan Mascaró, it asks:

Who knows the truth? Who can tell whence and how arose this universe? The gods are later than its beginning: Who therefore knows whence comes this creation? Only he who sees in the highest heaven: He only knows whence came this universe and whether it was made or un-created. He only knows, or perhaps he knows not.

The poet who wrote this verse points out the fundamental problem of epistemology: We don’t know some things and may not even have any way of determining what we don’t know. Some questions may be intrinsically unanswerable. Or the answers may be contradictory. The “Isha Upanishad,” a Sanskrit text from the first millennium B.C., attempts to describe a reality that escapes common sense: “It moves and it moves not, it is far and it is near, it is inside and it is outside.”

A second problem is that perception fundamentally limits our ability to apprehend reality. A prosaic example is the perception of color. Eagles, turtles, bees, and shrimp sense more and different colors than we humans do; in effect, they see different worlds. Different perceptual realities can create different cognitive or conceptual realities.

Jorge Luis Borges pushed this idea to the limit in his story “Funes the Memorious,” about a man who acquires a sort of infinite perceptual capacity. Borges writes: “A circle drawn on a blackboard, a right triangle … are forms that we can fully grasp; … [Funes] could do the same with the stormy mane of a pony … with the changing fire and its innumerable ashes.” Funes’ superpower sounds wondrous, but there is a catch. Borges writes that Funes was “almost incapable of ideas of a general, Platonic sort. Not only was it difficult for him to comprehend that the generic symbol dog embraces so many unlike individuals of diverse size and form; it bothered him that the dog … (seen from the side) should have the same name as the dog … (seen from the front).” The precision of Funes’ perception of reality prevents him from thinking in the coarse-grained categories that we associate with thought and cognition—categories which, necessarily rough, texture our imagined reality.

The arbitrariness of categories was the subject of another Borges story, “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins,” in which Wilkins imagined dividing animals into those belonging to the Emperor, those that are crazy-acting, those painted with the finest brush made of camel hair, those which have just broken a vase, those that from a long way off look like flies, and other oddly specific groupings.

The philosopher Michel Foucault, in his book The Order of Things, drew inspiration from Borges’ stories to reflect on the nature of categorization. He suggested that the categories and concepts that we define control our bounded cognition and, in their intrinsic arbitrariness, structure the realities that reside in our minds.

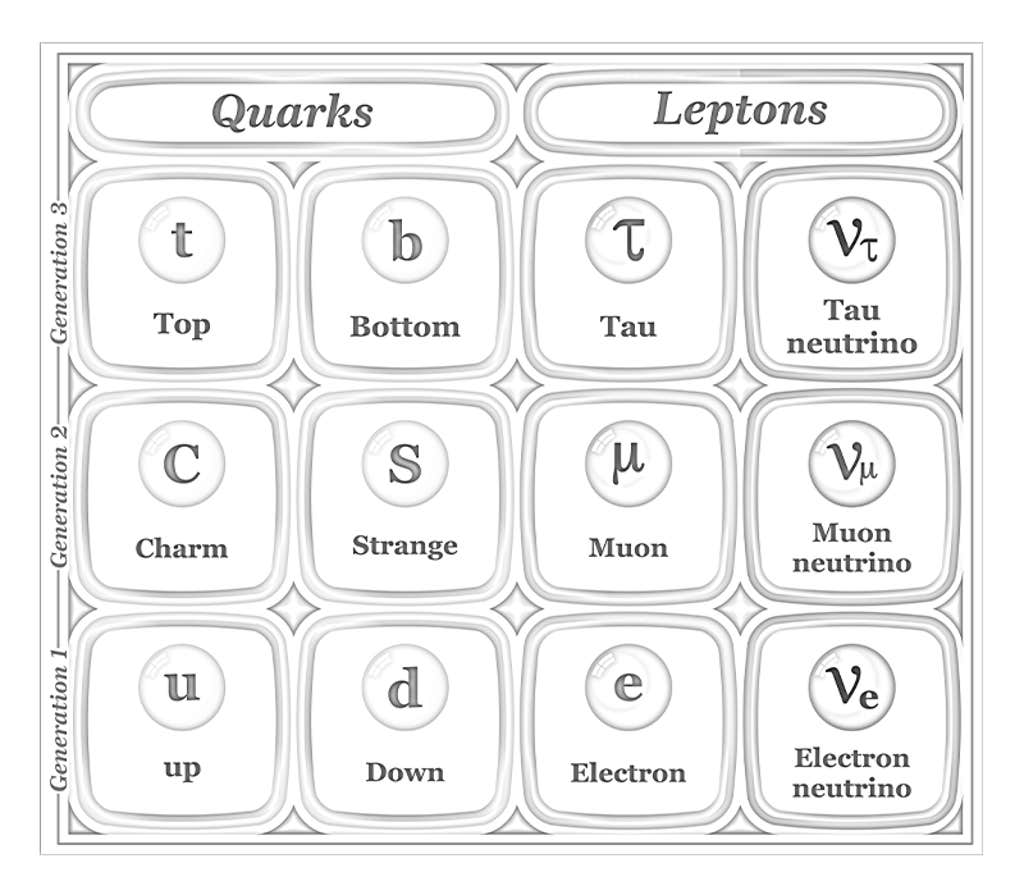

Foucault’s analysis resonates with me because it reminds me of categories in physics. For example, we routinely tell our students and the public that the world consists of particles called quarks and leptons, along with subatomic force fields. Yet these are concepts that reify a certain approximate sketch of the structure of the world. Physicists once thought that these categories were fundamental and real, but we now understand them as necessarily inexact because they ignore the finer details that our instruments have just not been able to measure.

If our categories determine the reality we perceive, can having an idea call a reality into being? This question is a version of the “simulation hypothesis,” whereby all of reality as we know it is simply a simulation in some computational engine, or perhaps a version of the idealism of Plato, where things that we can conceive in the world echo imperfectly an ideal that is the true reality.

Consider, for example, Mymosh the Self-begotten, the tragic hero of a story by Polish writer, Stanislaw Lem, in his volume The Cyberiad. Mymosh, a sentient machine self-organized by accident from a cosmic garbage heap, conjures up entire worlds and peoples just by imagining them. Are those people real, or are they all in his head? In fact, is there a difference? After all, Mymosh’s imagination is a physical process—electrical impulses in his brain. So perhaps the people he imagines are real in some sense.

Things exist and there is a truth about them, but we have no way of finding it out.

Some of these philosophical conundrums have concrete avatars in theoretical physics. Consider the notion of “duality” between physical theories. In this context, a “theory” means a mathematical description of a hypothetical universe, which we develop as a stepping-stone to understanding the actual universe in which we live. Two theories are said to be “dual,” or equivalent, if every observable in one matches some observable in the other. In other words, the two theories are different representations of the same physical system. Often in these dualities the elementary variables, or particles, of one theory become the collective variables, or lumps of particles, of the other, and vice versa. Dual theories scramble some of the most basic categories in physics, such as the difference between “bosonic” particles (any number of which can be in the same place at the same time) and “fermionic” particles (no two of which can be in the same place at the same time). These two kinds of particles have entirely different physical properties, so you would think that they could not be equivalent. But through dualities, it turns out that lumps of bosons can act like fermions, and vice versa. So, what’s the reality here?

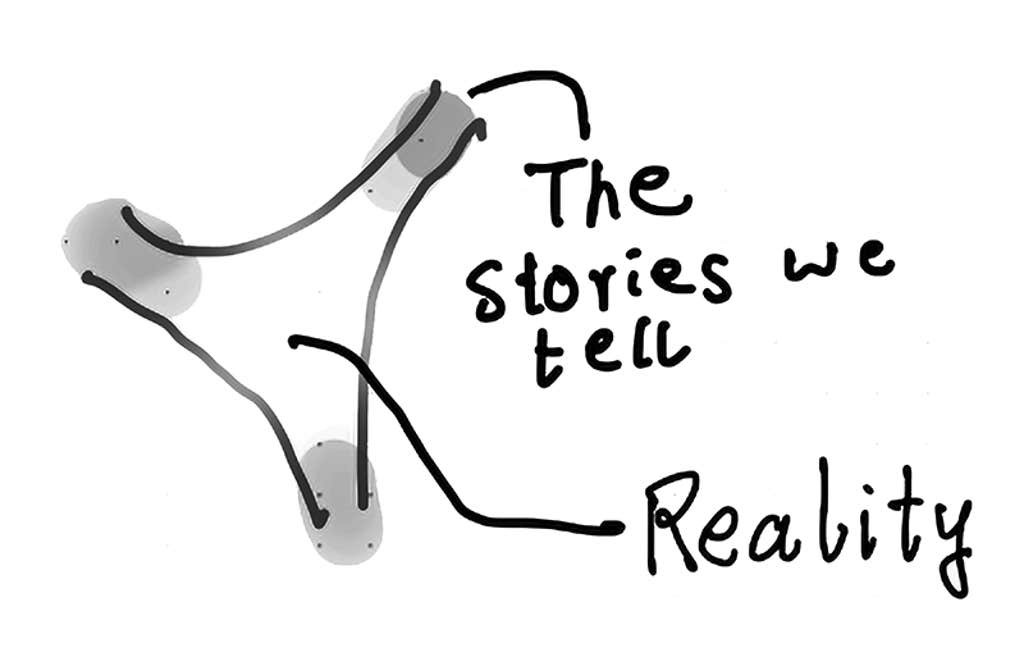

Even more dramatic are dualities involving the force of gravity. On one side, we have theories of matter and all the forces except gravity; on the other, we have theories of matter and forces including gravity. These theories look very different. They are couched in terms of different forms of matter, different types of forces, and even different numbers of spacetime dimensions. Yet they describe precisely the same fundamental physics. So, what is “real” here? If one theory says the force of gravity operates and the other says it doesn’t, what do we conclude about the reality of gravity? Perhaps we can use my sketch to visualize the situation—we are able to tell stories about the corners of this diagram of possible worlds, where simplifications and approximations suffice, but the categories and concepts that we have been capable of, at least to date, fail to describe the interior where reality is actually located.

Quantum mechanics makes things even more confusing. Quantum-mechanical states of a system can be combined, or superposed, in seemingly contradictory ways. So, the spin of an electron can be in a superposition of pointing up and down—an idea that might seem akin to suggesting that, say, a cat can be in a superposition of alive and dead. Does that mean these objects are in both states or neither state? Some theories suggest that measuring a cat (to continue with this metaphor) could cause it to collapse into a state of aliveness or deadness; others, evoking something like the many-worlds theory, suggest that the combined superposition continues through time. This is a casse-tête, a head breaker.

Where does this leave me? Perhaps we can reconcile all these ideas by following Ludwig Wittgenstein, who proposed in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, possibly referencing previous ideas of Søren Kierkegaard, that the theories and concepts we build are like ladders or nets we use to reach the truth, but we must throw them away upon getting there. I myself am trying to find my way by working in multiple fields, both physics and neuroscience, studying both the world and the mind that perceives it, because I believe that the quest to understand the reality of the universe must contend with the truncations imposed by the perceptual and cognitive limitations of the mind.

Should we bother seeking truths about the world in light of the doubts I have set out? I am hardly the first to ask. Socrates, according to Plato, remarked to Meno: “I would contend … that we will be better [people], braver and less idle, if we believe that one must search for the things one does not know, rather than if we believe that it is not possible to find out what we do not know and that we must not look for it.”

I am with Socrates on this one—his attitude is wise and pragmatic. If there is a reality and a truth about it, we will be better off and more likely to find it by searching, rather than assuming that it is not there. And even if the search, and the ladders we use to climb obstacles, do not lead us to the truth, we will enjoy the journey. ![]()

Lead image by Tasnuva Elahi; with photos by Vijay Balasubramanian