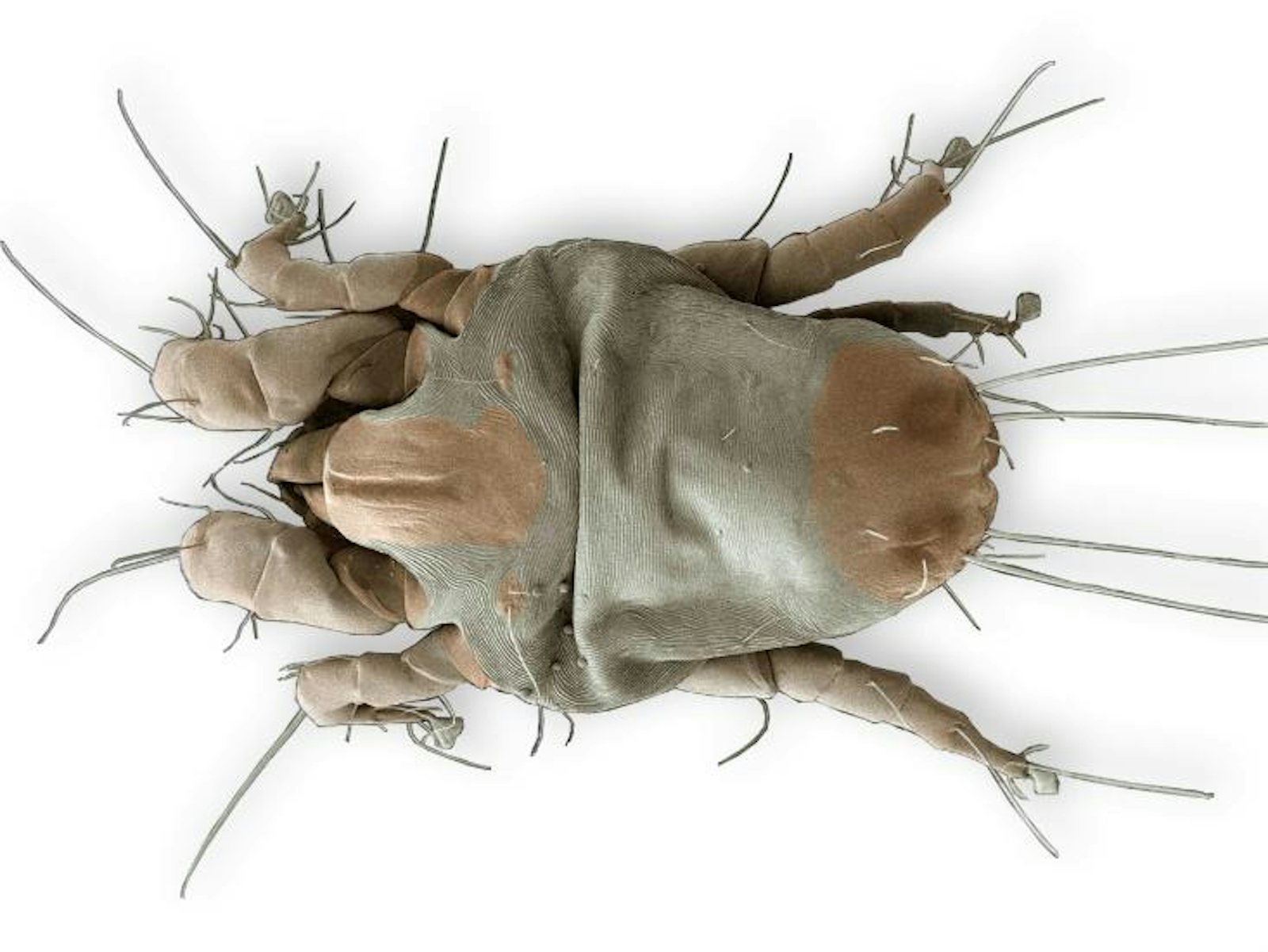

We have long known that we can catch germs while traveling. Recent years have shown that we can also bring home bed bugs. This holiday season, a PLoS One study informs us that by merely plopping into the seat of a car or airplane, we can unknowingly pick up dust mites—microscopic 8-legged arthropods that eat the dead parts of our bodies such as skin scales, dandruff flakes, and hair. Dust mites are eyeless, headless, and heartless, yet they’re expert travelers. They’ve been trekking around the world for 400 million years; in the modern era, they travel fast and in style, stowing away inside our seat cushions, luggage, and clothes. Although dust mites don’t directly harm us, they trigger allergies in about a billion people. But we aren’t allergic to the buggers themselves. We’re allergic to their poop.

The feces of dust mites isn’t just a byproduct of digestion, but a potent, biologically active substance vital to their procreation. There isn’t much to eat in the mites’ austere, dusty habitat, says Pavel Klimov at Michigan University, one of the study authors. So they developed a very strong digestive enzyme—a protein called cysteine protease, which helps them break down tough material that is available to them, like dead cells. After consuming a food particle, a mite envelops it with a special membrane. Into that blob the bug injects cysteine protease, which begins breaks down the food. Then the mite absorbs some of the nutrients and excretes the remaining mixture of partially digested food and enzyme. These fecal pellets serve as nourishment for young mites, who pick them up and eat them after the adults.

But for humans that poop is harmful. When it comes in contact with our skin or lands in our lungs, the enzyme erodes our cells as if they are food. “Those [fecal] particles are very small and they can be easily get airborne,” says Klimov. “They break up our delicate cell membranes and that causes allergies.” The reactions range from rhinitis (drippy nose), to atopic dermatitis (a form of eczema), to asthma. These biological insults are powerful enough that they can cause allergic reactions even in people who are normally not allergic to them. Klimov, who is not allergic, says that after being exposed to several million mites without protective respirators for about 30 minutes in his lab, he could barely breathe. (Dust mites actually carry over 20 different allergens; cysteine protease is the strongest.)

Modern house mites take their origin from parasitic mites that lived and travelled on birds, feeding on feathers. Later some mites migrated into the birds’ nests, switching their diet to dust and debris, says Klimov. And when we began building houses, the mites moved in there, as well. This new, very widespread habitat has been a windfall for a few successful types of mite. Rubaba Hamid, a zoologist at the University of Rawalpindi in Pakistan, initiated the recent PloS study to find out what mites inhabited houses in her home province of Pothwar. “People were being diagnosed with the house-dust-mite allergy but there had not been a single report that there actually were mites here or not,” she says.

Equipped with a vacuum cleaner and a very fine filter, she spent a year gathering dust from over 300 homes. An average gram of dust, she found, contained up to a thousand Dermatophagoides farina and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus individuals, 10 times the amount necessary to produce an allergic reaction in susceptible people. When she brought her mites to Klimov’s lab in Michigan and sequenced their DNA, she found that, with exception of a few insignificant mutations, the Pathwar mites were identical to those found in the USA. “It’s the same population that has spread out around the world,” Hamid says.

This hardy population is successfully dug into our couches, rugs, featherbed, and down pillows. You can’t vacuum them out completely because they burrow too deep. Chemicals such as benzoates shrink their population temporarily, but can have harmful side effects on humans. Some exterminators recommend placing down pillows and comforters into freezers, but mites are so hardy they can withstand temperature down to –4 Fahrenheit (–20 Celsius). Keeping houses dry is the best way to keep them in check—when humidity drops to 50-60 percent mites begin drying out—although they can ride out droughts by clumping together and climbing on top of each other to preserve moisture. Not only do our efforts to evict them fail, but we keep providing them with new habitats. For example, David Clarke, a researcher at the National University of Ireland, studies a relatively novel breeding and dispersal habitat for mites: children’s car seats.

Human travelers can easily pick up a small colony by the seat of their pants or the back of the sweater; even a brief cushion touchdown can leave you with a small colony. But because mite infestation is nearly universal, worrying about spreading them is futile—they probably beat you to your destination already. “They have been found on trains, planes, and even submarines,” says Clarke. So if you brought home a few migrant mites on your sweater, chances are their relatives are already feeding poop to their offspring in your couch.

Lina Zeldovich is Nautilus’ associate editor.