When renowned long-distance swimmer Benoît Lecomte set off from Hawaii in the summer of 2019, he didn’t expect to uncover a new ecosystem. He was simply going for a swim. In the year prior he had freestyled his way from Japan to Hawaii; now he would continue from Hawaii to California, but with a twist. He wanted to go through a region of the ocean that almost no one ever visits, let alone swims through, a region synonymous in the public imagination with environmental degradation: the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Created by systems of circular currents that act almost like giant whirlpools, pulling debris inside and trapping it there, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch spans roughly 600,000 square miles. The name is something of a misnomer—it evokes floating islands of junk, whereas miniscule fragments of plastic account for most of the garbage—but the patch is unquestionably polluted. Since its discovery in 1997, it has catalyzed attention to the problem of oceanic trash.

For all its prominence, though, relatively little is known about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Very few people have actually been there. People have sailed through it, and some even took water samples—but unless you’re swimming, or at least much closer to the water than is typically allowed on a trans-oceanic vessel, it’s difficult to truly get a sense of what lives there.

People have been thinking about “garbage patches” all wrong.

There have been hints, however, that there is more than garbage to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Charles Moore, the oceanographer who gave the region its popular name, prefers to call it Neptune’s Desert Nursery. There the air is comparatively warm and dry; the waters are calm; and swimming within them are multitudes of creatures. Yet aside from Moore, mostly people know the region only for its pollution.

So when Lecomte began his swim, we scientists had a simple question: What is actually out there?

Fortunately, Lecomte needed help. Not only did he need his boat crew, who would sail ahead of him and supply him with food, water, and a place to sleep; he needed a guide to and through the garbage patch, which is unevenly distributed and constantly shifting. We—a team including Fiona Chong of the University of Hull, Matthew Spencer of the University of Liverpool, Nikolai Maximenko of the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and myself—could provide him with up-to-date information during his swim. Then he could tell us what he saw.

Stroke by stroke by stroke, from morning until evening, Lecomte swam for weeks. Our team used oceanographic data and models to monitor the patch’s movements, remotely guiding Lecomte to where we predicted high concentrations of debris. While Lecomte swam, a member of his crew sampled the ocean surface: For roughly 30 minutes at a time he dipped a net, hauled up whatever it collected, and photographed the contents before removing any trash and returning the life back into sea. Before Lecomte entered the garbage patch, the net came up largely empty. After he entered, the net was suddenly full of life.

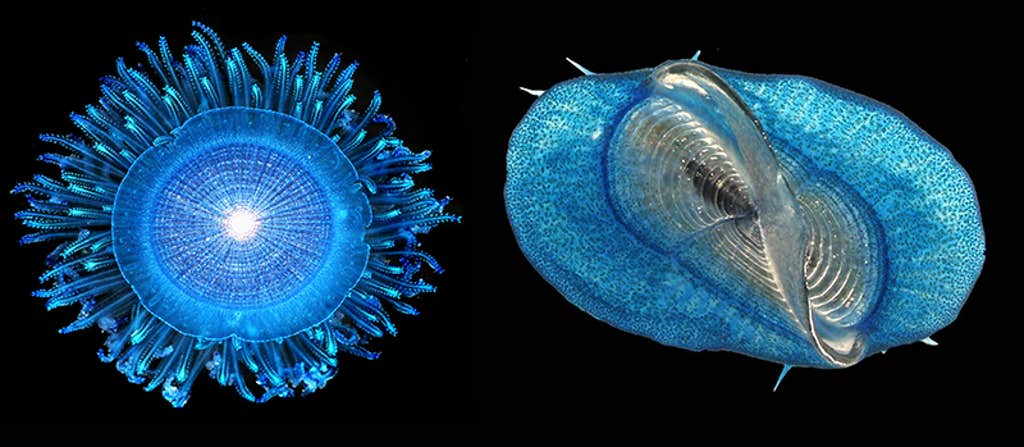

As we described in a study published earlier this year in PLoS Biology, amidst the floating plastic was a sea of floating organisms.1 One of the most immediately striking species were blue button jellies, who have a central disc-shaped float that can range from only a millimeter wide to the width of my palm. Surrounding the float is a ring of stunning cerulean and azure tentacles, pulsing like the shimmer of a star.

The more plastic we found, the more life we found.

Along with the blue buttons were their close relatives, the by-the-wind sailors. Like blue buttons, these jellies float on the ocean surface, but they’re oval rather than round and from their float rises a stiff ridge-like sail they use to harness the wind.

Many species above and below the waves prey on jellies, including sea turtles and albatross, but some of their main predators were in the nets beside them. Violet snails float upside-down at the ocean’s surface; they dip their body into the air to capture bubbles, which they wrap in snail slime and assemble into a raft. Their shells are as thin as a chicken egg but their bodies are heavy, and if they let go of the bubble raft they sink. They can’t swim, but simply wait until they bump into blue buttons and by-the-wind sailors for a meal.

Another oft-observed creature were blue sea dragon nudibranchs, who, like violet snails, also eat jellies and cannot swim. They swallow air to stay afloat and have hand-like appendages that they spread in wait for prey. And just like Charles Moore said when he called the garbage patch a nursery, we also found many very small animals, only a few millimeters wide—suggesting that the region isn’t just a place where floating life collects, but also a place where it reproduces.

Floating life seems to concentrate there, a thousand miles from shore, in the calm and quiet at the center of swirling currents. When we quantified the amount of plastic and the amount of life, they lined up: The more plastic we found, the more life we found. And there are four more such regions worldwide, including the North Atlantic Garbage Patch, located in the Sargasso Sea. There, currents concentrate floating golden algae, and hundreds of species use the resulting floating forest as a shelter.2

In the Sargasso Sea research we were unable to examine how floating creatures interacted with the plastic. Most likely don’t come in contact with it at all; they’re simply carried by the same currents. But back in the North Pacific Garbage Patch, researchers led by Linsey Haram at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center found that many organisms actually live and breed on rafts of floating plastic.3

People have been thinking about “garbage patches” all wrong. These regions of the ocean are not impoverished spaces. They’re ecosystems. Ecosystems that we’ve clumsily named after something we did to them—“garbage patches”—rather than what they may actually be. In both the North Atlantic and the North Pacific, we now know that these regions may be oases of life at the ocean’s surface.

For all its prominence, relatively little is known about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

People rightly want to reduce the amount of plastic in the sea. One organization, The Ocean Cleanup, uses kilometer-wide floating nets, dragged behind fuel-guzzling ships, to “clean” these parts of the ocean where plastic has concentrated—but there is no way to do so without also collecting, and in the process destroying, the amazing life within it. On land this would be obvious: We would never use a bulldozer to collect plastic from a meadow. The ocean’s surface is so little understood, though, that it’s difficult for people to imagine what might be out there.

This is why we must prevent plastic from entering into the ocean in the first place.

As Lecomte left the so-called garbage patch, that meadow of floating life thinned, and by the time he reached California the sampling nets again came up mostly empty. So concluded his journey, remarkable not only as a feat of strength and endurance but for what he helped discover—and what he found is just the beginning.

In 2022 I founded the Neuston Net Research Collective, which works with people sailing through these neglected realms to survey their life. Who knows what will yet be encountered? And this much is already clear: The ocean’s so-called garbage patches are so much more than we thought. These floating oases are strange, mysterious, and almost completely unknown. It’s time to explore them. ![]()

Lead image: Rich Carey / Shutterstock

References

1. Chong, F., et al. High concentrations of floating neustonic life in the plastic-rich North Pacific Garbage Patch. PLOS Biology 21, e3001646 (2023).

2. Helm, R.R. the mysterious ecosystem at the ocean’s surface. PLOS Biology 19, e3001046 (2021).

3. Haram, L.E., et al. Extent and reproduction of coastal species on plastic debris in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Nature Ecology & Evolution 7, 687-697 (2023).