This article is part of series of Nautilus interviews with artists, you can read the rest here.

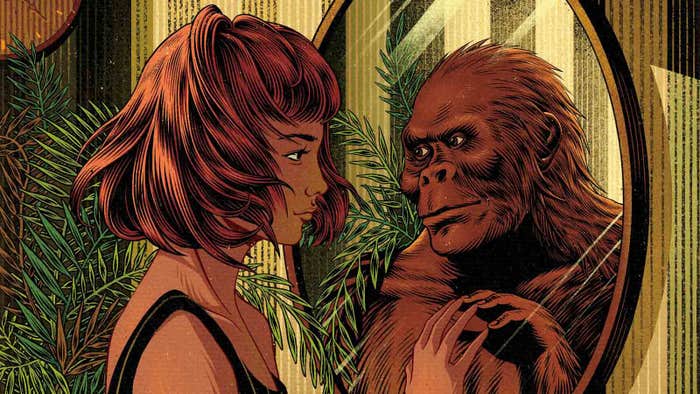

Angie Wang is a Los Angeles-based artist who has thought a lot about AI, and even more about what it means to be a human. Her illustrated essay for The New Yorker titled “Is My Toddler a Stochastic Parrot?” explores the similarities and differences between haphazard human development and the advance of large language models. It was also a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Illustrated Reporting and Commentary.

Wang’s work celebrates the ineffable and often messy aspects of the human condition in bold colors. That’s one reason she was the perfect choice to illustrate the cover of Nautilus’ Rebel Issue. We recently spoke to her about her creative process, artificial intelligence and art, and the future of human expression.

How did you decide pursuing art was the path you wanted to take?

It’s the only thing I’m good at! That’s actually true—I’ve always drawn a lot, but I graduated from college during the 2008 recession with carpal tunnel syndrome and the only job skill I had that didn’t aggravate my wrists was, weirdly enough, drawing.

You created the cover for our Rebel Issue about scientific rebels and rebellion—is there anything in science that particularly inspires you?

I actually studied linguistics in college as my undergraduate major, and I’m still especially interested in language. But it’s been a long time since I’ve been in that world.

Is there anything you think scientists can learn from artists—or vice versa?

I think that the humanities are excellent at allowing us to access the nuances of another individual’s experience. Art and writing allow us to peer into each other’s lives in a very granular way, and with a lot of depth … and are better able to represent the computational irreducibility of an individual life—which we all have to live, so that’s why it’s relevant.

But I also think that many artists might find it exciting to look beyond the world of symbols and feelings to investigate truths about the world that go deeper than our everyday experiences. Science gives us an awareness of a shared reality beyond our own lives.

They’re different levels of understanding the world—understanding another human being’s interior experiences, or understanding math, an amoeba, or a star. Multiple levels of understanding are nice to have. We live in the world and we live lives; both of those things are true.

How do you approach a creative project? Walk us through your process.

For illustration, I read the brief and do a quick brainstorming session where I write down 10-15 words, and then recombine them to see if I can get any ideas. Then I make some sketches based on those ideas, turn them in, and flesh out the sketch that’s chosen. It’s not very romantic, to be honest. It’s a lot of sitting at my computer drawing while I watch a mediocre thriller on Netflix.

You’ve created some illustrated essays that feature animation. How does your creative process change when you’re juggling so much at once?

Oh, it’s about the same. Drawing is a puzzle where you know the image needs something here or there based on what you want to say or what effect you want it to have, and animating is that with in-betweens. It’s meditative, and somewhat tedious. That’s why you need the mediocre thriller on Netflix.

One of your recent illustrated essays was a piece for The New Yorker, “Is My Toddler a Stochastic Parrot?”, which compared your child’s development to ChatGPT. There’s some existential angst in that piece where you write, “Why spend weeks painstakingly coloring all this when a diffusion model could generate the whole thing for me?” Do you see any role for generative AI in your work?

Not in mine, personally! I knew I needed a very specific visual language for the essay, for example, and I needed it to be a representation of my lived reality rather than something a diffusion model would produce by abstracting from a lot of different artwork. Every part of it had to be infused with care and realism for it to sing properly.

Of course there’s something existentially tempting about knowing that if I didn’t care about the exact nature of what I was producing, I could instantly generate a product that … wouldn’t actually look like my art, but who cares, right? The temptation is that it produces things fast, and without effort. Wouldn’t it be cool to imagine something and have it come into being right away?

But spending your effort on something brings you to a certain timeless space to think through what you want to say, and allows you to infuse your perspective and your individual quirks and choices into your art. When you let a machine handle the details for you, you can get tricked into anchoring your vision to whatever’s been prefabricated for you, simply because what it produces is finished—a fully baked image (averaged from the creations of many other skilled artists). A finished image can trick your mind into thinking it’s a good image, but they aren’t the same thing.

And because it’s not truly your creation, whatever generative AI produces can make you feel pleasantly surprised, as if you were perceiving a perfectly lovely drawing from someone else (which you are, from many “someone elses”)—instead of vulnerable and disappointed by how far short you’ve fallen of your original vision. So I understand why it’s tempting. It skips over the excruciating parts of being an artist.

But it’s just not a process I’m really interested in. That being said, I do think diffusion models are probably a better match for other kinds of artists who have a different workflow and a different desired final product. I like the exploration of a blank page better than iteration through many different pieces, and I like style and originality better than speed or realism.

Is there something different about the frustration artists feel when comparing their art to AI art versus when they compare it to the art that other humans make?

Well, to be honest, I think human artists mostly feel violated because their work and their friends’ work has been sucked up into this machine, without their consent, and milled into a fine powder, to be reconstituted in a new shape divorced from the context and labor and perspective that produced it, for consumption by people who don’t really care about art, mostly to produce images of women with giant boobs.

To be fair, I actually find a lot of generative image-making practices to be very sweet—in my research for the piece, I trawled r/StableDiffusion and r/DALLE2 and thought it was charming that so many people there are delighted by their newfound ability to generate images. But there’s a lot of exploitation that had to happen for that, and in practice, there’s also an element of mimicry that feels especially violating. And now there’s also a massive wave of slop drowning our voices out.

In that piece you also write, “Human obsolescence is not here and never can be.” Have any of the advancements in generative AI since you’ve published caused your confidence in that to waver?

Are fish made obsolete by submarines? You might say horses were made obsolete by cars, but only with regard to widespread use as transportation for humans. Horses are not obsolete to other horses, or to the humans who love them, or to the world at large.

I think that when people fear obsolescence they understand it in terms of their ability to be useful in the world, to contribute labor or insight or value. But understanding your value in the world as being mediated by your utility—your usefulness, your impressiveness—is a large part of what I’m arguing against in the piece. The question I ask in the essay boils down to this: If babies aren’t made obsolete by AI, then how could any human be made obsolete by AI?

It is pretty yuck that some people might believe other humans can be replaced by generative AI. There’s a lot wrong with treating other people as easily replaced tools—and it’s not just an ethical or moral issue, but also a misunderstanding of what generative AI is capable of. You can see that in aggregate this kind of thing is rotting the internet from the inside out.

For the record, I do think the technology behind generative AI is very cool. It’s cool that these deep statistical correlations are more powerful at modeling complex systems like language than boiling them down to symbolic models! But we need a better framework for understanding what’s going on than anthropomorphic approaches like “AI is human” or “AI is smart.”

Do you have any upcoming projects you’re excited about?

I’m about to put out another piece with The New Yorker—it’s a light-hearted animated piece about my parents and my toddler. I’m also working on a graphic novel about femininity, dance, and cults.

Interview by Jake Currie.

Lead image courtesy of Angie Wang.