This article is part of series of Nautilus interviews with artists, you can read the rest here.

Artist John Hendrix says he doesn’t remember a time in his life when he wasn’t drawing, and it shows. His illustrations—which have appeared in Esquire, The New Yorker, and Sports Illustrated, to name a few—ripple with the frenetic energy of an avid sketcher, disciplined by decades of experience.

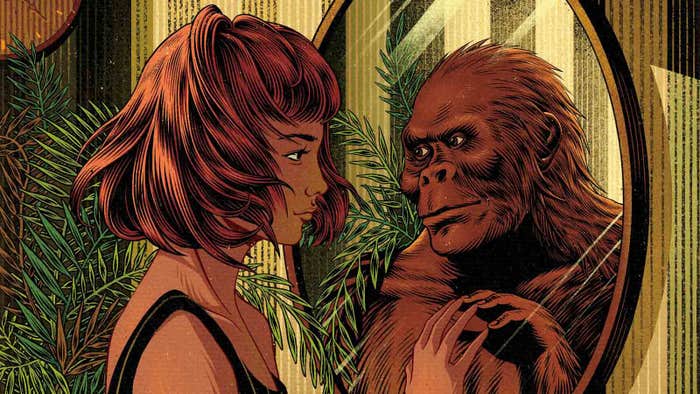

Hendrix is also a New York Times bestselling illustrator and children’s book author whose book covers beckon readers with the promise of adventure. That’s not the only reason he was the perfect artist to illustrate the cover story of Nautilus Issue 53 about the transformative power of the hero’s journey; Hendrix also illustrated several stories in the inaugural online issue of Nautilus, kicking off our journey as well. His Nautilus cover recently received recognition in Communication Arts magazine as a winner of its annual illustration competition. We spoke to him about his creative process, the difference between writing and illustrating, and his thoughts on artificial intelligence and art.

How did you decide pursuing illustration was the path you wanted to take?

I don’t remember a time before drawing in my life, but I was in college when I realized what illustration was as a category of activity that I loved. I met a wonderful illustration professor named Barry Fitzgerald, who introduced me to the true professional landscape and practice of illustration. It was there at the University of Kansas where I realized I had been an illustrator my whole life, and never really knew it. From that time forward it became the path I most wanted to follow.

Does your creative approach change if you’re working on a commissioned piece versus something more personal or recreational? Walk us through your process.

The way that I draw and think never really changes from personal projects to sketchbook drawings to commission work. The main difference between these activities is the process to create ideas and generate the best work. I use a lot of iteration. I make stuff quickly and evaluate it and try to make it better. Oftentimes, my best ideas don’t come from “thinking of a good idea” but from the act of drawing itself. Whether I’m in my sketchbook or being commissioned for a magazine illustration, my first activity is to just begin drawing. From there, the drawings themselves lead to the next idea.

A lot of your work is incredibly elaborate, and your sketchbooks in particular give the impression that you could keep drawing for days. How do you know when a project is finished?

Yes, my drawings often give the impression of a maximalist aesthetic which is true visually but I try to design them so that they are clear and easy to understand. I have found over the years that work improves dramatically in the first, second, or third iteration but beyond that you reach a point where the idea can only improve incrementally and perhaps even get worse.

In addition to illustrating other people’s books, you also write and illustrate your own. How does your process change when you’re not just illustrating someone else’s text, but writing and illustrating your own?

I never thought of myself as a writer growing up, but I am one now. The category may be “accidental writer,” because I use writing as a way of conveying the things I want to talk about in my work. I use it as a tool to generate the kind of drawings and stories I want to tell that, of course, offer their own challenges, but I also love writing for existing manuscripts. The challenge of working with text that you cannot change produces images you might never have created on your own.

You’ve created the art for several different stories for Nautilus over the years: Do you have a favorite?

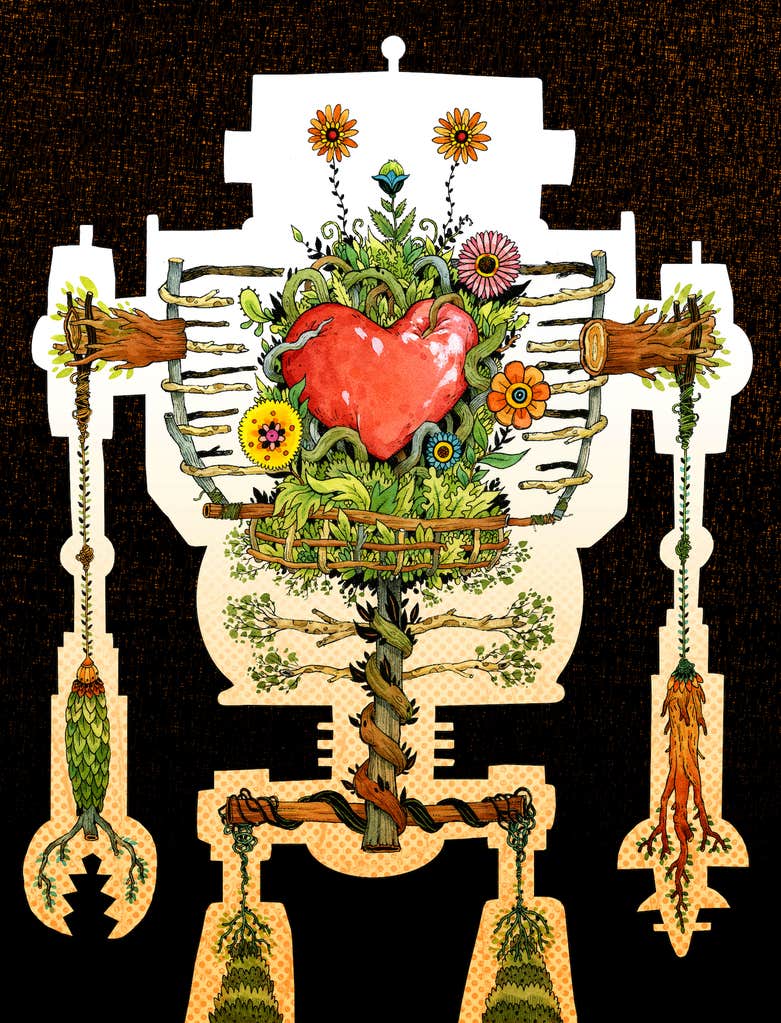

Believe it or not, I was the illustrator for the entire first online issue of Nautilus magazine, and in that issue I did several images that I still love to this day. Like “Love Bot,” a giant robot with interior guts that are all made of organic material, for an article asking if robots will ever have human emotions.

Is there anything you think scientists can learn from artists—or vice versa?

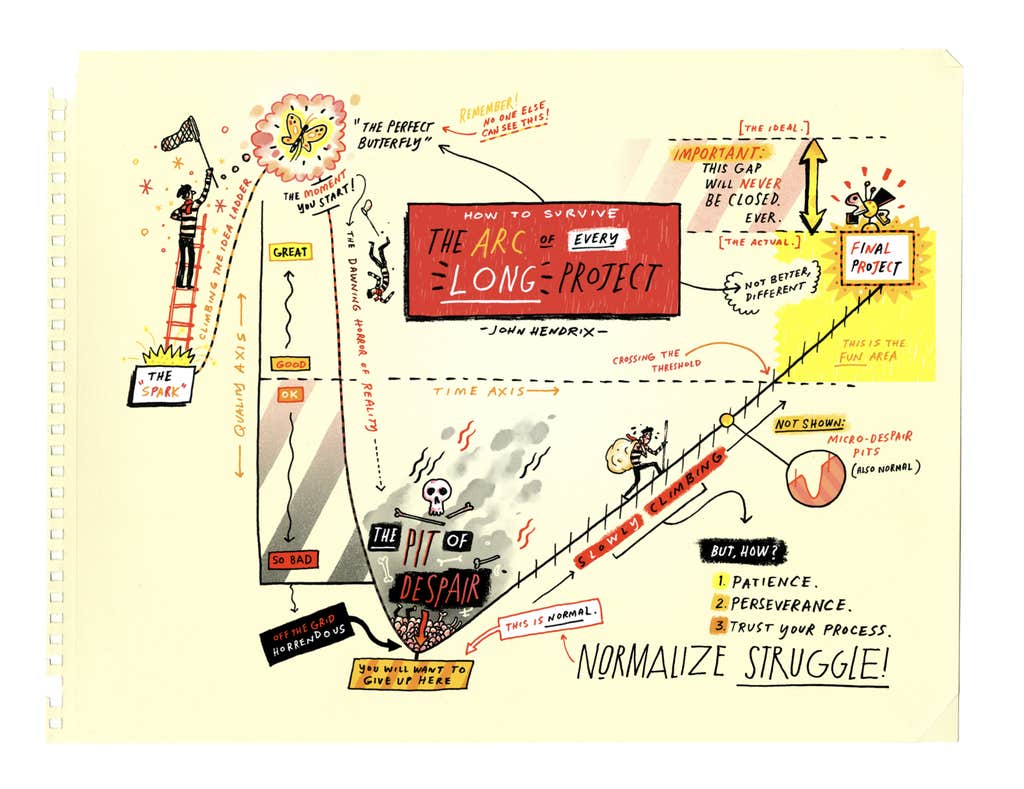

I’m certain the answer is yes. As a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, I often get annoyed at the artificial divide that people make between the humanities and STEM—it seems like a strange distinction to make in a world of infinite learning. I made a chart for the artists and illustrators in my graduate program (MFA Illustration and Visual Culture) about the psychological contours of every long project; I lovingly call it the pit of despair. I made this for artists, and yet the people who respond to it the most are in fact, scientists! Even people working on their Ph.D. and business professionals have seen the same pattern in their own work. So it’s a universal human phenomenon—we just can’t realize our ideas like we first imagined them!

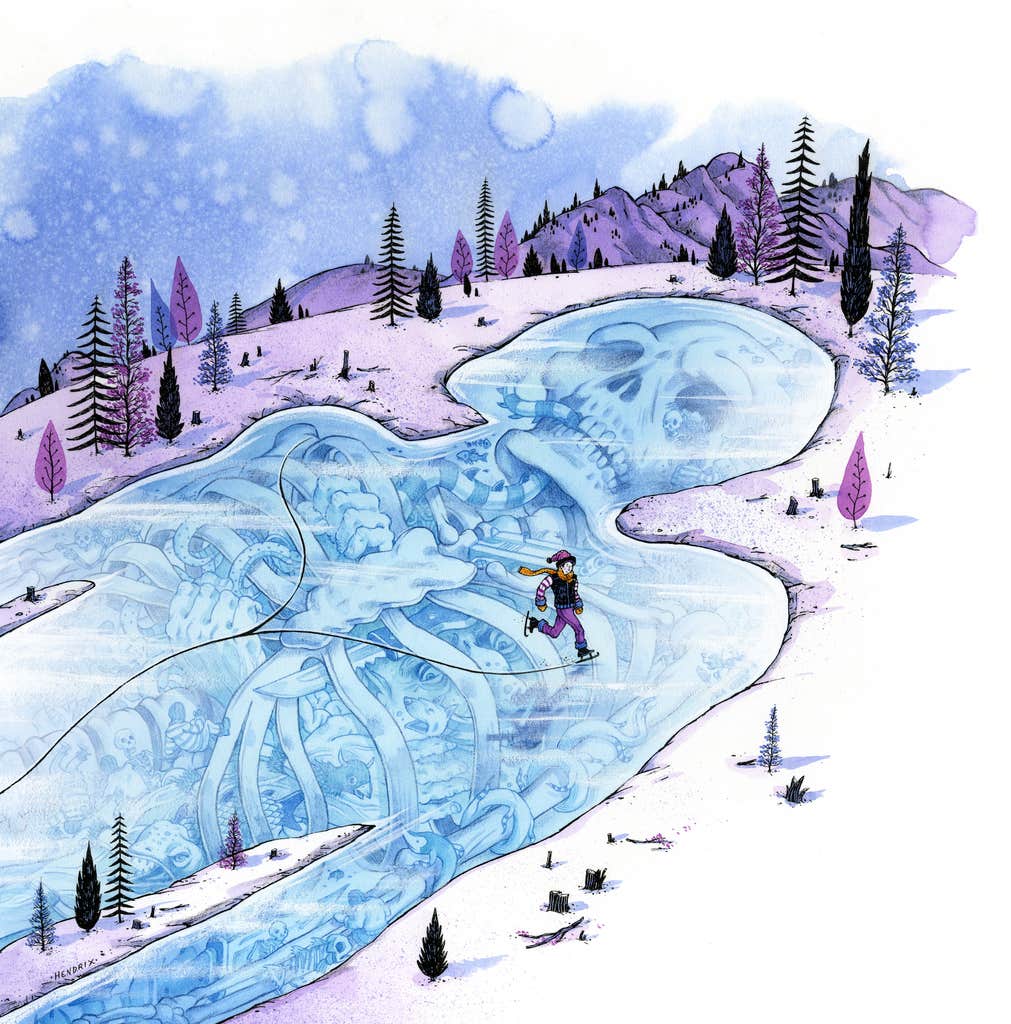

Most recently, you created the cover for Nautilus Issue 53 about the transformative power of the “hero’s journey.” What about that story captured your imagination?

This story was such a great project for me. I have done a lot of thinking and reading about the hero’s journey over the last five years as I’ve been working on an upcoming graphic novel that touches on those themes. The piece was beautifully written, and asked a lot of the questions we all have about our lives. In my work, I love creating images that help translate the complex to the clear, and this was one of those times when an image can help illuminate and translate narrative into image and vice versa.

You also have a graphic novel coming out about two masters of the hero’s journey—J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. What made you decide to write about them?

The project started as a love letter to the works by two writers that impacted my life from a young age. But even though the book is centered around their story, and their fellowship, the heart of the tale is about asking the questions about the origin of mythology itself. Where do stories come from? Why do stories matter at all? The book helps young readers trace the history of the fairytale to the concept of the hero’s journey. Lewis and Tolkien’s lives serve as interpreters for the deepest questions of why humanity longs to build secondary worlds of their own.

The rise of generative AI services like Midjourney is causing some controversy in the art world. What are your thoughts on the use of AI to create art?

I just gave a paper on this subject at a recent conference. In short, many people seem to believe that AI image generators are either a trend, a tool, or a tragedy. But, in the long run, it will be all three. I’m not actually worried about it, believe it or not. For instance, no AI could have created the image I made for this story. AI is more of (what they call in Silicon Valley) a “Demo Baby”—something that looks great and amazing on a big stage demonstration, but with less proven practical application to real world briefs and client demands.

Have you experimented with any of these programs or do you see a role for them in your work?

I haven’t used it much in my own practice, but I do know some that use it for comps and for generating different compositional ideas. No one uses its output for the actual final art. I think the end use of this stuff will be mostly for ad agencies and production studios to create comps, that they will show to actual artists they hire to create the final art. They will say, “Can you make ‘This Kind of Thing’?” and the artist will look at it and then ignore 90 percent of it and make their art.

Do you have any upcoming projects you’re excited about?

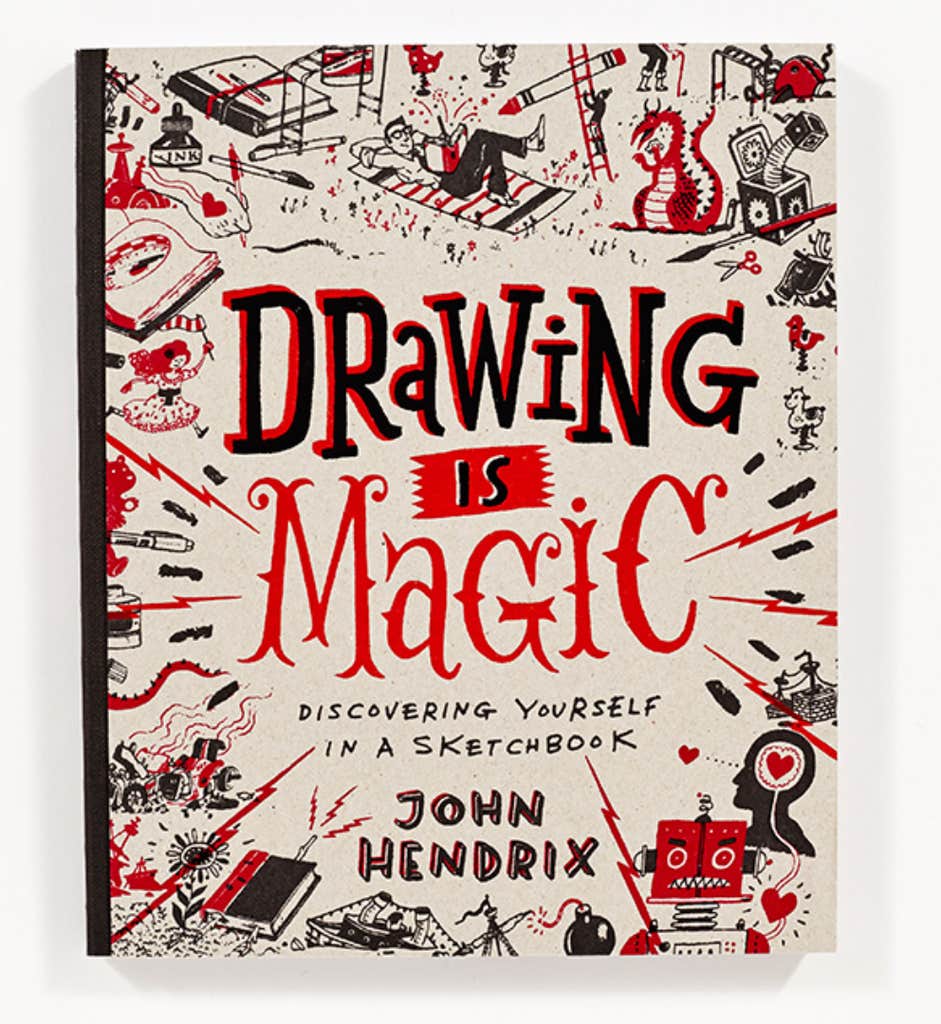

Mythmakers comes out in the fall of 2024, and the current project on my desk is a book called 100 Things: The List that Unlocks your Best Ideas, a sequel to my workbook Drawing is Magic. I’m very excited to return to the cinematic universe of Drawing is Magic, which will have been out for 10 years when 100 Things is released.

Interview by Jake Currie.

Lead image courtesy of John Hendrix.