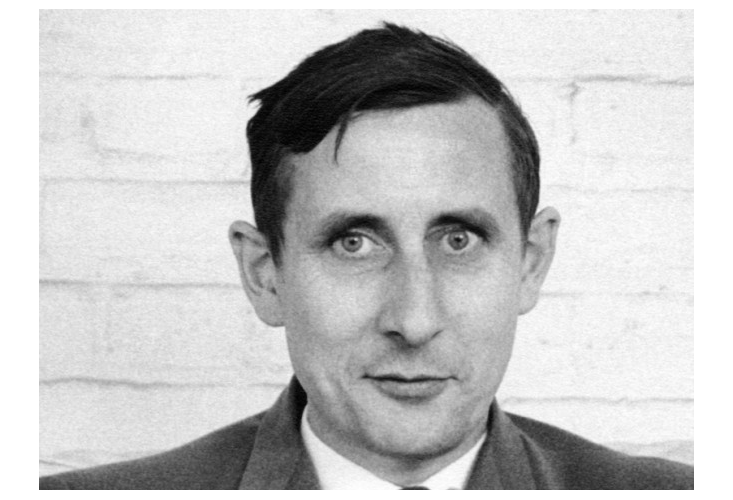

All through a long life I had three main concerns, with a clear order of priority. Family came first, friends second, and work third.”

So writes the pioneering theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson in the introduction to his newly published collection of letters, Maker of Patterns. Spanning about four decades, the collection presents a first-person glimpse into a life that witnessed epochal changes both in world history and in physics.

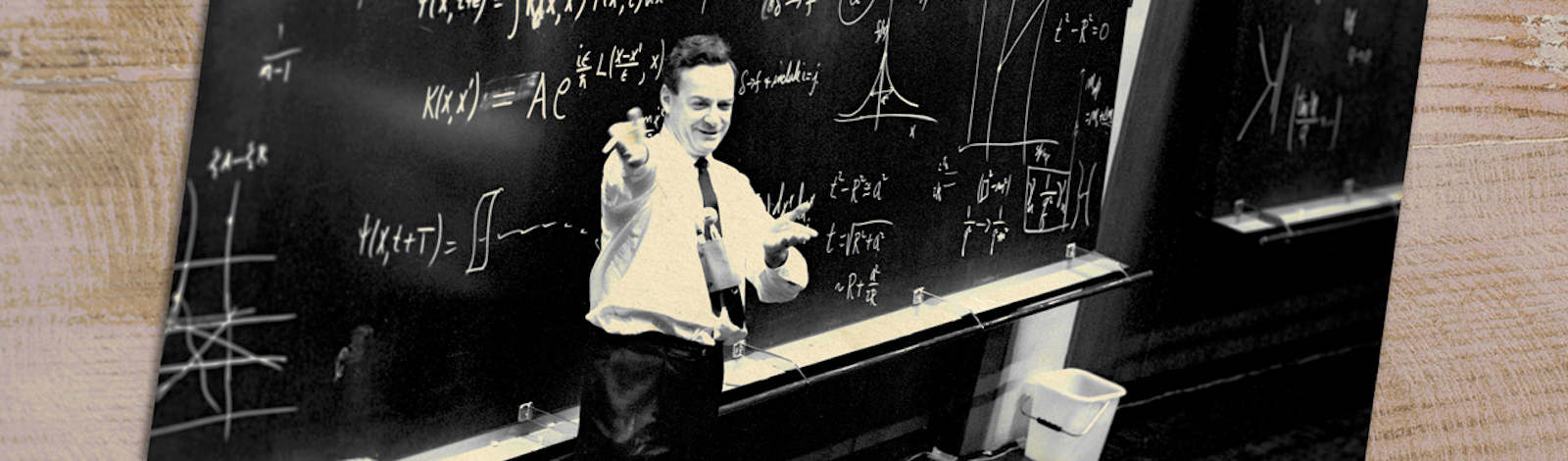

Here, we present short excerpts from nine of Dyson’s letters, with a focus on his relationship with the physicist Richard Feynman. Dyson and Feynman had both professional and personal bonds: Dyson helped interpret and draw attention to Feynman’s work—which went on to earn a Nobel Prize—and the two men traveled together and worked side by side.

Taken together, these letters present a unique perspective of each man. Feynman’s effervescent energy comes through, as does Dyson’s modesty and deep admiration for his colleague. So too does the excitement each scientist felt for his role in uncovering some of the foundations of modern-day theoretical physics.

November 19, 1947

Just a brief letter before we go off to Rochester. We have every Wednesday a seminar at which somebody talks about some item of research, and from time to time this is made a joint seminar with Rochester University. I am being taken in Feynman’s car, which will be great fun if we survive. Feynman is a man for whom I am developing a considerable admiration; he is the brightest of the young theoreticians here and is the first example I have met of that rare species, the native American scientist. He has developed a private version of the quantum theory, which is generally agreed to be a good piece of work and may be more helpful than the orthodox version for some problems. He is always sizzling with new ideas, most of which are more spectacular than helpful and hardly any of which get very far before some newer inspiration eclipses them. His most valuable contribution to physics is as a sustainer of morale; when he bursts into the room with his latest brain wave and proceeds to expound it with lavish sound effects and waving about of the arms, life at least is not dull.

…

The event of the last week has been a visit from Peierls, who has been over here on government business and stayed two nights with the Bethes before flying home. He gave a formal lecture on Monday about his own work, and has been spending the rest of the time in long discussions with Bethe and the rest of us, at which I learnt a great deal. On Monday night the Bethes gave a party in his honour, to which most of the young theoreticians were invited. When we arrived we were introduced to Henry Bethe, who is now five years old, but he was not at all impressed. The only thing he would say was “I want Dick. You told me Dick was coming,” and finally he had to be sent off to bed, since Dick (alias Feynman) did not materialise. About half an hour later, Feynman burst into the room, just had time to say “so sorry I’m late. Had a brilliant idea just as I was coming over,” and then dashed upstairs to console Henry. Conversation then ceased while the company listened to the joyful sounds above, sometimes taking the form of a duet and sometimes of a one-man percussion band. …

March 8, 1948

…

Yesterday I went for a long walk in the spring sunshine with Trudy Eyges and Richard Feynman. Feynman is the young American professor, half genius and half buffoon, who keeps all physicists and their children amused with his effervescent vitality. He has, however, as I have recently learned, a great deal more to him than that, and you may be interested in his story. The part of it with which I am concerned began when he arrived at Los Alamos; there he found and fell in love with a brilliant and beautiful girl, who was tubercular and had been exiled to New Mexico in the hope of stopping the disease. When Feynman arrived, things had got so bad that the doctors gave her only a year to live, but he determined to marry her, and marry her he did; and for a year and a half, while working at full pressure on the project, he nursed her and made her days cheerful. She died just before the end of the war.

I was wrong when I wrote that Feynman found his wife Arlene in New Mexico. He married her first in a city hall on Staten Island and then took her with him to New Mexico. The story is movingly told by Feynman in the book What Do You Care What Other People Think? (1988), the title being a quote from Arlene.

As Feynman says, anyone who has been happily married once cannot long remain single, and so yesterday we were discussing his new problem, this time again a girl in New Mexico with whom he is desperately in love. This time the problem is not tuberculosis, but the girl is a Catholic. You can imagine all the troubles this raises, and if there is one thing Feynman could not do to save his soul, it is to become a Catholic himself. So we talked and talked and sent the sun down the sky and went on talking in the darkness. At the end of it, Feynman was no nearer to the solution of his problems, but it must have done him good to get them off his chest. I think that he will marry the girl and that it will be a success, but far be it from me to give advice to anybody on such a subject.

March 15, 1948

…

My own work has taken a fresh turn as a result of the visit of Weisskopf last week. He brought with him an account of the new Schwinger quantum theory which Schwinger had not finished when he spoke at New York. This new theory is a magnificent piece of work, so at the moment I am working through it and trying to understand it thoroughly. After this I shall be in a very good position, able to attack various important problems in physics with a correct theory while most other people are still groping. One other very interesting thing has happened recently; our Richard Feynman, who always works on his own and has his own private version of quantum theory, has been attacking the same problem as Schwinger from a different direction and has now come out with a roughly equivalent theory, reaching many of the same ideas independently. Feynman is a man whose ideas are as difficult to make contact with as Bethe’s are easy; for this reason I have so far learnt much more from Bethe, but I think if I stayed here much longer, I should begin to find that it was Feynman with whom I was working more.

June 25, 1948, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Feynman originally planned to take me out west in a leisurely style, stopping and sightseeing en route and not driving too fast. However, I was never particularly hopeful that he would stick to this plan, with his sweetheart waiting for him in Albuquerque. As it turned out, we did the eighteen hundred miles from Cleveland to Albuquerque in three and a half days, and this in spite of some troubles; Feynman drove all the way, and he drives well, never taking risks but still keeping up an average of sixty-five miles per hour outside towns. It was a most enjoyable drive, and one could see most of what was to be seen of the scenery without stopping to explore; the only regret I have is that in this way I saw less of Feynman than I might have done. …

Sailing into Albuquerque at the end of this odyssey, we had the misfortune to be picked up for speeding; Feynman was so excited that he did not notice the speed limit signs. So our first appointment in this romantic city of homecoming was an interview with the justice of the peace; he was a pleasant enough fellow, completely informal, and ended up by fining us ten dollars with $4.50 costs, while chatting amiably about the way the Southwest was developing. After this Feynman went off to meet his lady, and I came up by bus to Santa Fe.

Going into a sort of semistupor as one does after forty-eight hours of bus riding, I began to think very hard about physics.

All the way Feynman talked a great deal about his sweetheart, his wife Arlene who died at Albuquerque in 1945, and marriage in general. Also about Los Alamos. I came to the conclusion that he is an exceptionally well-balanced person, whose opinions are always his own and not other people’s. He is very good at getting on with people, and as we came West, he altered his voice and expressions unconsciously to fit his surroundings, until he was saying “I don’t know noth’n” like the rest of them.

Feynman’s young lady turned him down when he arrived in Albuquerque, having attached herself in his absence to somebody else. He stayed there for only five days to make sure, then left her for good and spent the rest of the summer enjoying himself with horses in New Mexico and Nevada.

September 14, 1948, 17 Edwards Place, Princeton

…

On the third day of the journey a remarkable thing happened; going into a sort of semistupor as one does after forty-eight hours of bus riding, I began to think very hard about physics, and particularly about the rival radiation theories of Schwinger and Feynman. Gradually my thoughts grew more coherent, and before I knew where I was, I had solved the problem that had been in the back of my mind all this year, which was to prove the equivalence of the two theories. Moreover, since each of the two theories is superior in certain features, the proof of equivalence furnished a new form of the Schwinger theory which combines the advantages of both. This piece of work is neither difficult nor particularly clever, but it is undeniably important if nobody else has done it in the meantime. I became quite excited over it when I reached Chicago and sent off a letter to Bethe announcing the triumph. I have not had time yet to write it down properly, but I am intending as soon as possible to write a formal paper and get it published. This is a tremendous piece of luck for me, coming at the time it does. I shall now encounter Oppenheimer with something to say which will interest him, and so I shall hope to gain at once some share of his attention. It is strange the way ideas come when they are needed. I remember it was the same with the idea for my Trinity Fellowship thesis.

My tremendous luck was to be the only person who had spent six months listening to Feynman expounding his new ideas at Cornell and then spent six weeks listening to Schwinger expounding his new ideas in Ann Arbor. They were both explaining the same experiments, which measure radiation interacting with atoms and electrons. But the two ways of explaining the experiments looked totally different, Feynman drawing little pictures and Schwinger writing down complicated equations. The flash of illumination on the Greyhound bus gave me the connection between the two explanations, allowing me to translate one into the other.

As a result, I had a simpler description of the explanations, combining the advantages of Schwinger and Feynman. …

September 30, 1948

…

One thing which I must always keep in mind to prevent me from getting too conceited is that I was extraordinarily lucky over the piece of work I have just finished. The work consisted of a unification of radiation theory, combining the advantageous features of the two theories put forward by Schwinger and Feynman. It happened that I was the only young person in the world who had worked with the Schwinger theory from the beginning and had also had long personal contact with Feynman at Cornell, so I had a unique opportunity to put the two together. I should have had to be rather stupid not to have put the two together. It is for the sake of opportunities like this that I want to spend five more years poor and free rather than as a well-paid civil servant.

November 1, 1948, Hotel Avery, Boston

…

After my last letter to you I decided that I needed a long weekend away from Princeton. I persuaded Cécile Morette to come with me to see Feynman at Ithaca. This was a bold step on my part, but it could not have been more successful, and the weekend was just deliriously happy. Feynman himself came to meet us at the station, after our ten-hour train journey, and was in tremendous form, bubbling over with ideas and stories and entertaining us with performances on Indian drums from New Mexico until one a.m.

Feynman was obviously anxious to talk and would have gone on quite indefinitely if he had been allowed.

Cécile Morette was the brightest of the young physicists who arrived at the institute at the same time as I did. She was the only one who quickly grasped the new ideas of Feynman. We immediately became friends. The fact that she happened to be female was irrelevant to our friendship. She was a natural leader, she understood modern mathematics better than I did, and she had a great sense of humor.

The next day, Saturday, we spent in conclave discussing physics. Feynman gave a masterly account of his theory, which kept Cécile in fits of laughter and made my talk at Princeton a pale shadow by comparison. He said he had given his copy of my paper to a graduate student to read, then asked the student if he himself ought to read it. The student said no, and Feynman accordingly wasted no time on it and continued chasing his own ideas. Feynman and I really understand each other; I know that he is the one person in the world who has nothing to learn from what I have written, and he doesn’t mind telling me so. That afternoon Feynman produced more brilliant ideas per square minute than I have ever seen anywhere before or since. In the evening I mentioned that there were just two problems for which the finiteness of the theory remained to be established; both problems are well-known and feared by physicists, since many long and difficult papers running to fifty pages and more have been written about them, trying unsuccessfully to make the older theories give sensible answers to them. When I mentioned this fact, Feynman said, “We’ll see about this,” and proceeded to sit down and in two hours, before our eyes, obtain finite and sensible answers to both problems. It was the most amazing piece of lightning calculation I have ever witnessed, and the results prove, apart from some unforeseen complication, the consistency of the whole theory. The two problems were the scattering of light by an electric field, and the scattering of light by light.

After supper Feynman was working until three a.m. He has had a complete summer of vacation and has returned with unbelievable stores of suppressed energy. On the Sunday Feynman was up at his usual hour (nine a.m.), and we went down to the physics building, where he gave me another two-hour lecture of miscellaneous discoveries of his. One of these was a deduction of Maxwell’s equations of the electromagnetic field from the basic principles of quantum theory, a thing which baffles everybody including Feynman, because it ought not to be possible. Meanwhile Cécile was at mass, being a strict Catholic. At twelve on the Sunday we started our journey home, arriving finally at two a.m. and thoroughly refreshed. Cécile assured me she had enjoyed it as much as I had. I found a surprising intensity of feeling for Ithaca, its breezy open spaces and hills and its informal society. It seemed like a place which I belonged to, full of nostalgic memories. I suppose it really is my spiritual home. …

February 28, 1949, Chicago

On Thursday we had Feynman down to Princeton, and he stayed till I left on Sunday. He gave in three days about eight hours of seminars, besides long private discussions. This was a magnificent effort, and I believe all the people at the institute began to understand what he is doing. I at least learnt a great deal. He was as usual in an enthusiastic mood, waving his arms about a lot and making everybody laugh. Even Oppenheimer began to get the spirit of the thing and said some things less sceptical than is his habit. Feynman was obviously anxious to talk and would have gone on quite indefinitely if he had been allowed; he must have been suffering from the same bottled-up feeling that I had when I was full of ideas last autumn. The trouble with him is that he never will publish what he does; I sometimes feel guilty for having cut in front of him with his own ideas. However, he is now at last writing up two big papers, which will display his genius to the world; and it is possible that I have helped to make him do this by making him conscious of being cut in on, which if it be true is a valuable service on my part. …

October 23, 1965

We are all excited because my three friends Tomonaga, Schwinger, and Feynman won the Nobel Prize. You may remember that it was just after their great work in 1947 that I started my career by carrying further what they had begun. I am happy that the prize is given to the three of them equally. To some extent I can take credit for this, since Schwinger originally had all the limelight and Tomonaga and Feynman were struggling in obscurity. It was my big paper “The Radiation Theories of Tomonaga, Schwinger and Feynman” that first did justice to all three of them. I am now writing the historical account of their work which will appear next week.

Freeman Dyson is a theoretical physicist and mathematician, a professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study, and the author of Disturbing the Universe.

Adapted from Maker of Patterns: An Autobiography Through Letters by Freeman Dyson. Copyright © 2018 by Freeman Dyson. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Lead Photo Collage Credits: Cern; Pixabay