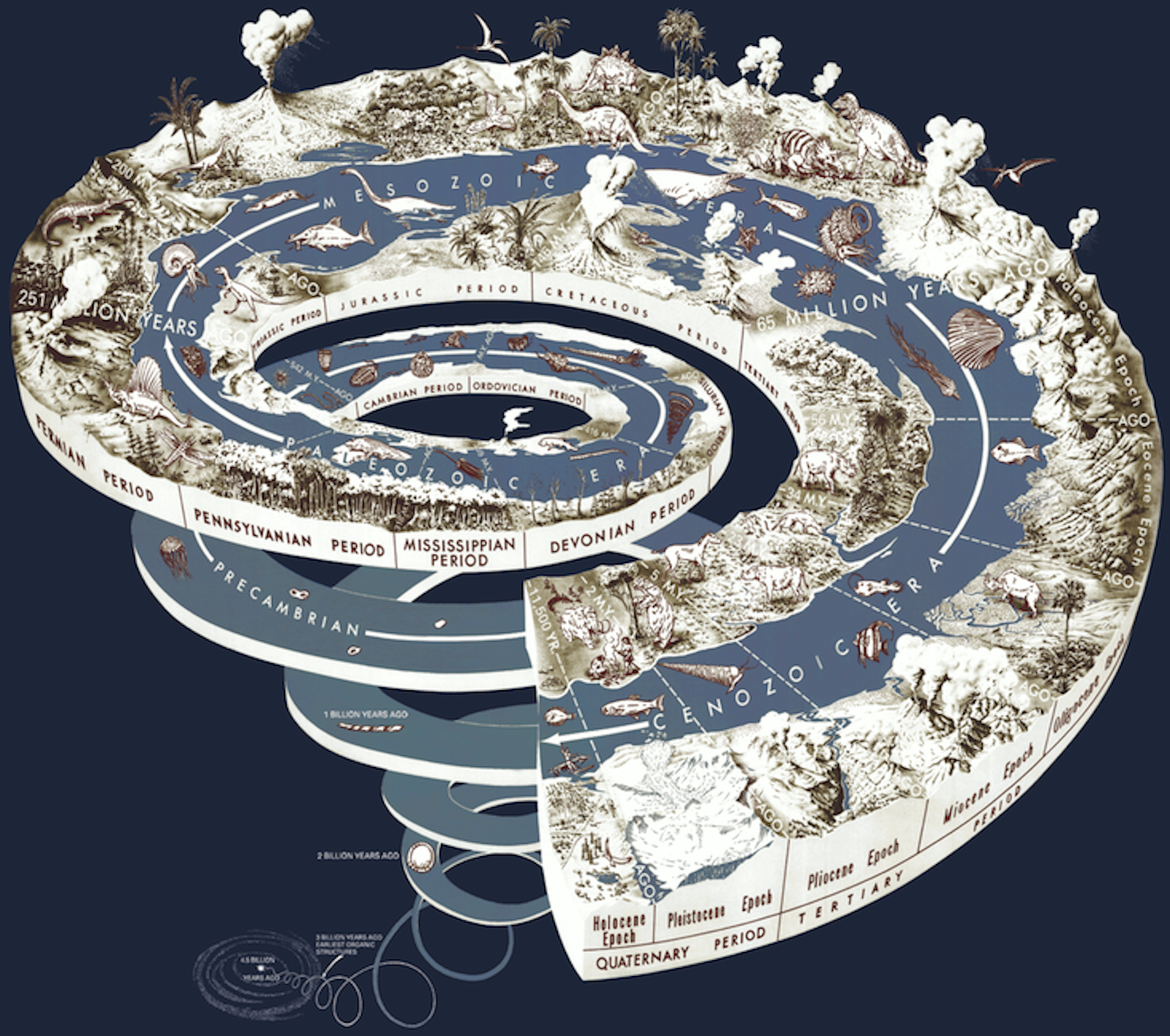

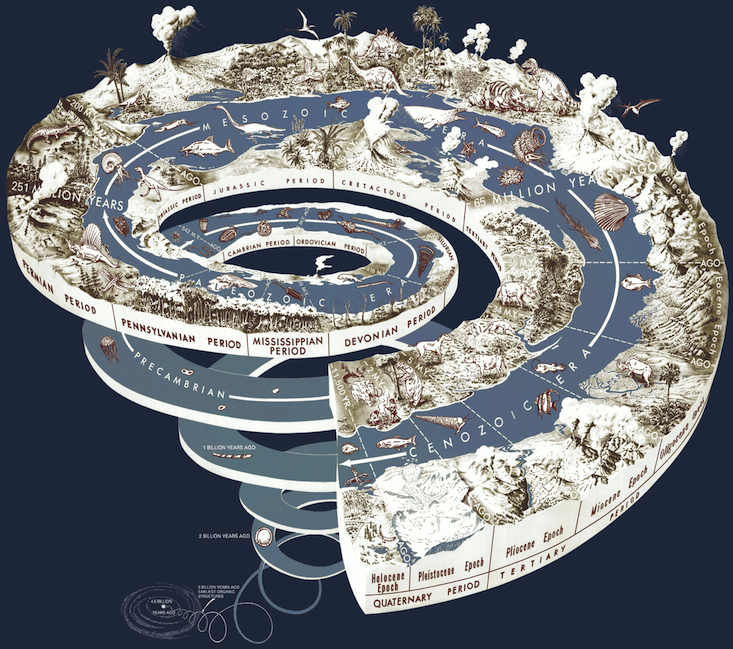

In the early 1990s, a few miles west of El Kef, a town in Tunisia, geologists set a small golden spike in between two layers of clay that remains there to this day. They wanted to mark the tiny yet striking layer of iridium—a hard, dense, silvery-white metal—sandwiched in the middle. It was deposited by debris falling from the atmosphere all over the world, 66 million years ago, after an asteroid hit the planet and wiped out 75 percent of Earth’s plant and animals species, including the dinosaurs. Geologists now recognize the iridium layer, no matter where it’s found, as the boundary between the end of Mesozoic era and the beginning of Cenozoic era that, as you can see below, continues to this day.

But, according to a Science report this year, that illustration of the Geologic Time Scale might need an update. It still says we dwell in the Holocene epoch, the most recent stage of the Cenozoic. Colin Waters, the lead author of the report, is a geologist with the British Geological Survey and secretary of the International Commission on Stratigraphy’s (ICS) Working Group on the Anthropocene, the “Age of Man.” The term is often used as shorthand for humanity’s outsize impact on the natural world. Waters, though, simply argues that since it’s possible to make out the geological boundary, we should name it. There are plenty of useful markers, he says—climatic, biological, and geochemical—to delineate the start of the Anthropocene from the end of the Holocene, just as the iridium layer marks the start of the Cenozoic. This fall, the ICS will meet in Capetown, South Africa, where the working group will present further findings supporting the addition of the Anthropocene to the Geologic Time Scale.

Lucy Edwards, though, isn’t ready to say goodbye to the Holocene. A geologist with the United States Geological Survey, with a background in paleontology and stratigraphy, she recently coauthored a paper with the geologist Stanley Finney in Geological Society of America Today, called “The ‘Anthropocene’ epoch: Scientific decision or political statement?” She thinks it’s too soon to tell whether humankind’s impact on the planet is producing a physical boundary as distinct as previous ones.

Nautilus spoke with both scientists, on separate occasions, to see if they could find common ground on the science of finding boundaries in Earth’s history, and why they matter.

When should we recognize the Anthropocene?

Edwards: I don’t think we’re standing too close to say that, “Yes, humans are altering the environment.” But I think we’re standing too close to say the Holocene is over. I actually feel optimistic, that if I could look back 100 years from now, maybe things would have changed for the good, and I hope not for the bad. And if, 100 years or 1,000 years from now, the human influence has kind of stabilized, then that would be the time to define the Anthropocene.

Waters: For nearly a century, geologists argued about whether it was valid to have a Holocene epoch, or whether it was just one interglacial of many interglacials over the last million years. There’s no criteria that says, “An epoch has to be this long.” If you look at a stratigraphic chart, things become shorter and shorter duration the closer you get to the current day. It’s just saying we have more information that we can subdivide on a finer scale. But if you look out your window, most of what we’re looking at is from the Holocene. We are now going through a significant change to the planet. So with the Anthropocene, we’re saying we have the justification to recognize that change to the sedimentary record that will be permanent. As soon as you can see a change from the state of the planet, irrespective of what’s causing it, that’s the reason for recognizing the boundary.

What is the point of naming layers of rock at all?

Edwards: Humans like to name things. They like to find similarities and differences and aggregate things for communication purposes. Humans have assigned names to different parts of time as best they can approximate them.

Waters: To a geologist, as soon as you say “Cretaceous,” you have a picture in your mind, of the animals and plants present, that it’s a warm planet with no polar ice caps. After the asteroid impact, you have very different characteristics. Victorian geologists recognized that there were packages of rocks that were distinct from each other. They spent their time trying to recognize the boundaries. Over the last 40, 50 years, geologists have tried to pinpoint those boundaries on the planet—“I know I’m seeing this boundary here on my part of the planet, and you’re seeing it on your part of the world, too.”

What’s the process of naming a geological boundary?

Edwards: It’s a committee decision. You get an international group to first figure out what they’re looking for, what defines the boundary. Originally it was what you had in the field—fossils of clams, snails, trilobites. Now it’s whatever you can use. It might be a geochemical signal, a fossil, or just some criterion that you think you can recognize worldwide or almost worldwide. You find the best sections you can that illustrate the boundary, then you pick a point that’s the defining point.

Waters: For the Carboniferous boundary, which ended nearly 300 million years ago, how many places would you find it well defined and exposed? Maybe a few dozen sites. But if you’re defining the Anthropocene, since it’s the present day, it’s the whole planet. So we have to limit where the best places are.

What are some potential ways to identify the beginning of the Anthropocene?

Edwards: One could easily define it in the rocks, or in lake sediments. But the goal of naming anything is to facilitate information, to make it easier to convey concepts to other people. Some people use the Anthropocene as a concept—humankind is now dominating its environment. Then you have to parse that assumption word by word: Is it all of humankind? What do you mean by dominate? Can you control earthquakes and volcanoes yet? What if we define the Anthropocene as starting 6,000 years ago? Would that make it less useful? How about 1850 AD? I can’t predict the future, but maybe 100 years from now we’ll say, “Well, after World War III, that’s when it starts.”

Waters: Radioactive fallout is a good candidate. If I were deciding, we’d use the plutonium section in the ground from around 1953. You could also use aluminum, pesticides, plastics, or carbon dioxide concentration. Generally boundaries tend to happen around major events, like a major continental collision, where you have mass extinctions. It’s an interesting analogy to what’s been happening over the last 300 years—we’re taking animals and plants and moving them across the whole planet because we find them functionally useful, essentially speeding up the process of continental collision, and instigating the sixth mass extinction along the way.

But of course that’s a slow process. If you were a geologist looking back at today, it would look like an instantaneous event, but today it’s happening too slowly to use as a tool. It’s not to say that human evolution didn’t have major milestones in the last 10,000 years, but they all start gradually and spread gradually. They’re not good as a geological signal. A whole host of new technologies come together after the Second World War, and it’s recognizable in the sediments. You could measure it in marine sediments, deep lake sediments, in glacial ice, speleothems—the layers of stalactites and stalagmites in caves—even tree rings. The options we’re looking at are laminated successions that are annual, so in theory you could count back.

Zach St. George is a freelance reporter based in California, writing about science and the environment. Follow him on Twitter @ZachStGeorge.