One question for Luis Ciria, a neuroscientist at the University of Granada, where he studies how the brain works under physical exertion.

Exercise is great for our brains too, right?

Probably not. At the beginning of our experiments about a decade ago, we believed that this idea, this hypothesis, was straightforward: that exercise must improve your brain because you improve the rest of your body—why not the brain? But after several experiments and reading the literature, we started to think maybe there are some big problems. We started to go deeper, and we realized that the literature is not solid enough to conclude these things.

It’s not that there is no effect. In our new paper, we only say that there is no strong or solid evidence to say that physical exercise improves our cognition. My feeling is that there is a small effect, but not big enough to improve our daily life. For example, to remember what I need when I go to a supermarket, I need a list even if I exercise a lot.

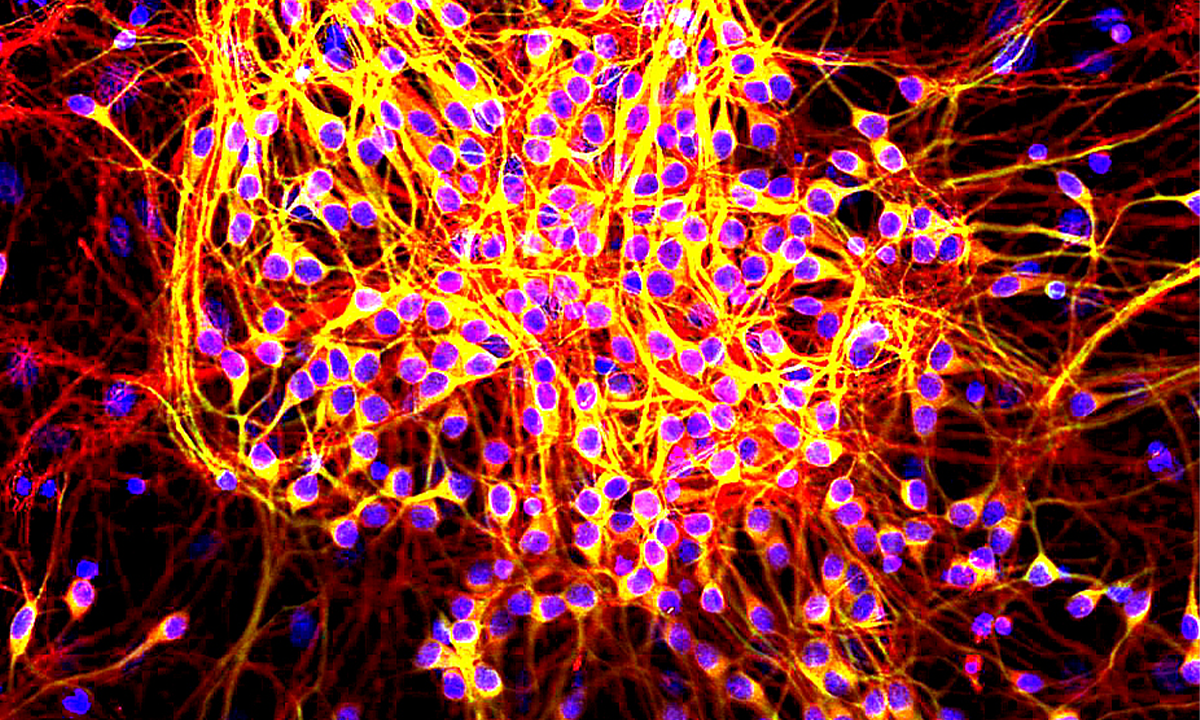

We have no idea what is going on inside our brain.

Before our review, some other reviews indicated that there is a small but positive effect. We went to the primary sources of evidence, all these randomized control trials, and show statistically that most of these randomized control trials are underpowered studies, meaning they have low sample sizes. So we cannot believe their results.

The idea behind these studies is that exercise is so good for many other things—for our cardiorespiratory systems, our muscles—but people tend to think of our brain as a muscle. So they say, “If you train your body and your brain, you will improve your cognitive function. It will show better performance.” But that's not the case. The brain doesn't work as a muscle. Some people point out that exercise increases blood flow in your brain. Or that it leads to higher releases of catecholamines, a neurotransmitter related to the stress response. But it's not clear. The brain is so complex. We have no idea what is going on inside our brain. It's so difficult. This is one of the main weaknesses of this literature.

In our review, we only focus on the physical component of exercise. But for example, there are some sports, like soccer or basketball, that incorporate core cognitive components. When you play basketball, it’s not just running or jumping. You also have to make decisions, pay attention—a lot of cognitive things at the same time. One of the points that we highlight in the paper is that maybe the combination of physical exercise and cognitive training together could improve our cognitive function. Of course, if you train your memory, you are going to improve your performance on a memory task. That's obvious. So in our review, we excluded the studies with yoga, for example, and tai chi, because these are physical activities which incorporate a really important cognitive component, where you’re focusing your mind or attention in one way or another. That's something that we need to investigate further.

If you ask me, if you exercise, are you going to feel better? No doubt. If you run 10 kilometers now, you're going to release stress. You're going to meet people, maybe make friends. You're going to form social bonds. It's going to be much better than if you go to your sofa and drink four beers and watch TV. If you exercise, you usually breathe clean air. You'll get some sun. You will sleep much better.

Sleeping well is so important for our mental and physical health, it’s amazing. It’s probably not the exercise that’s directly benefiting you. It’s sleeping well. Eating well, and being with people, relieves your stress. All these factors around exercise are what probably helps improve your brain, or slow down your cognitive decline, rather than the exercise itself. ![]()

Lead image: SpicyTruffel / Shutterstock