When Dan Scheffey turned 50, he threw himself a party. About 100 people packed into his Manhattan apartment, which occupies the third floor of a brick townhouse in the island’s vibrant East Village. His parents, siblings, and an in-law were there, and friends from all times and walks of his life. He told them how much they meant to him and how happy he was to see them all in one place. “My most important family,” says Dan, who has been single his entire life, “is the family that I’ve selected and brought together.”

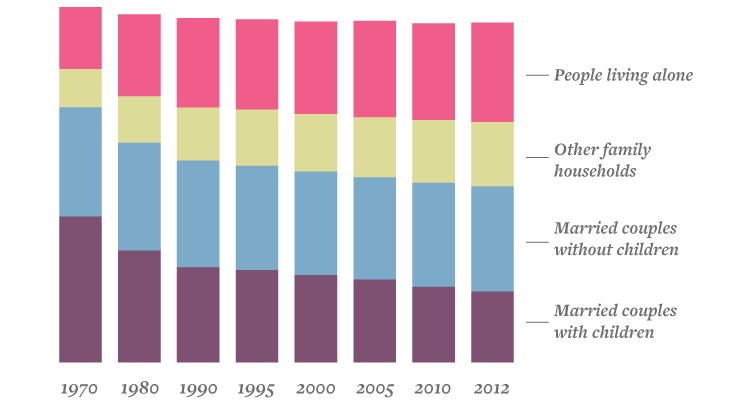

Dan has never been married. He doesn’t have kids. Not long ago, his choice of lifestyle would have been highly unusual, even pitied. In 1950, 78 percent of households in the United States had a married couple at its helm; more than half of those included children. “The accepted wisdom was that the post-World War II nuclear family style was the culmination of a long journey—the end point of changes in families that had been occurring for several hundred years,” sociologist John Scanzoni wrote in 2001.1

But that wisdom was wrong: The meaning of family is morphing once again. Fueled by a convergence of historical currents—including birth control and the rising status of women, increased wealth and social security, LGBTQ activism, and the spread of personal communication technologies and social media—more people are choosing to live alone than ever before.

Pick a random American household today, and it’s more likely to look like Dan’s than like Ozzie and Harriet’s. Nearly half of adults ages 18 and older are single. About 1 in 7 live alone. Americans are marrying later, divorcing in larger numbers, and becoming less interested in remarrying. According to the Pew Research Center, by the time today’s young adults reach age 50, a quarter of them will have never married at all.

The surge of singlehood is not just an American phenomenon. Between 1980 and 2011, the number of one-person households worldwide more than doubled, from about 118 million to 277 million, and will rise to 334 million by 2020, according to Euromonitor International. More than a dozen countries, including Japan and several European nations, now have even larger proportions of solo-dwellers than the U.S. (Sweden ranks highest at almost 50 percent.)2 Individuals, not couples or clans or other social groups, are fast becoming the fundamental units of society.

The rising tide of solo dwellers is creating, sustaining, and perhaps even strengthening, the ties that bind us.

And yet, in the stories we tell each other about the workings of community, it is often the married couples and the traditional families who are holding us together. In the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2015 opinion legalizing same-sex marriage, for instance, Justice Anthony Kennedy discounted the country’s 107 million singletons when he declared marriage “a keystone of the Nation’s social order.” We tend to view single people—especially those who live alone—as isolates, holed up in their apartment, lonely and loveless, more social repellent than social glue.

Research by social scientists paints a very different picture. Most singles, studies show, are more like Dan Scheffey than their miserable or narcissistic caricatures. They host salons, take classes, go to rallies, organize unions, care for aging friends and relatives, help raise kids, and cultivate large, diverse social networks—often with more zeal and commitment than the married demographic they’re displacing.

Rather than tear us apart, the rising tide of solo dwellers is creating, sustaining, and perhaps even strengthening, the ties that bind us.

The belief that nuclear families are essential to the social operating system has long infused our collective psyche. In late 19th-century France, Emile Durkheim, an eminent figure in sociology, proclaimed that marriage integrates people into society while single life alienates them. Because they lack social support and a sense of belonging, Durkheim argued, single people were more likely to kill themselves.

More than a century of statistical scrutiny tells us that any link between singlehood and asocial behavior, including suicide, has been vastly overstated, if one exists at all.3 And yet the stereotype persists. In our own research on the perceptions of single people, my colleagues and I presented study participants with pairs of near-identical biographical profiles, differing only in marital status. Participants routinely judged the married people as kinder, more loyal, and more caring. They tended to view the singles as shyer, lonelier, and more selfish.4

Not only are these biases false—they may be backward.5 In multiple national surveys involving representative samples of thousands of citizens, participants answered questions about their social life. How often did they socialize with friends, neighbors, or coworkers? How often did they give rides, help with errands, or pitch in with housework or repairs? Did they also offer advice, encouragement, or emotional support? Did they receive similar support in return?

There is some evidence that romantic coupling comes at the expense of other core relationships.

In every measure, single people as a group spend more time connecting with and helping others than their married counterparts. Singles are more likely to do the same for their parents and siblings. They also devote more time and resources to caring for aging relatives or friends who are sick, disabled, or elderly. These differences hold for people who have young children and those who don’t. They’re true for men and women, whites and non-whites, the rich and the poor, and the employed and the jobless.

In cities and towns, single people are cultivators of urban culture. Compared to married folk, they participate in more civic groups and public events. They go out to dinner more often and take more music and art classes.6 In studies that surveyed only men, bachelors were more likely than husbands to take part in professional societies, unions, and farm organizations. Single men also tend to be more generous with their money.7

Longitudinal studies, which follow people over many years, show these dynamics unfolding over time. One such study, published in the Journal of Marriage and Family in 2012, enlisted more than 2,700 representative Americans under age 50 who were not married or living with a partner (cohabitation), and then tracked them for six years.8 Those who stayed single kept in touch with friends and relatives. Those who wedded or entered into a cohabiting relationship, meanwhile, became more insular. They had less contact with their parents and siblings, and spent less time with friends than when they were single.

The shrinkage of partnered people’s social networks wasn’t just a honeymoon effect. After more than three years of marriage or cohabitation, with or without kids, couples were still less connected. Other research shows that when married people get divorced, their social networks expand again.

There is some evidence that romantic coupling also comes at the expense of other core relationships. In a recent study, the British anthropologist Robin Dunbar (who famously estimated that 150 is about the number of meaningful relationships a person can have at any one time) surveyed 540 people ranging in age from 18 to 69. He asked them to list all the people they felt they could turn to in times of “severe emotional or financial crisis.” Including their partner, coupled participants named, on average, one fewer than singles. The results, though far from definitive, suggest that when a singleton couples up, his or her lover replaces two former confidants.

Many single people maintain their diverse social ties even as they age, bucking the stereotype that singlehood dooms you to die alone. Consider Lucy Whitworth, a retired teacher and single mother-of-none living amongst gardens and fruit trees in an intentional community in California. When she was diagnosed with cancer at age 68, her friends mobilized. One person helped her make a list of everything she would need to do in the months ahead. Forty-eight others—square dance partners, bridge players, fellow volunteers—divvied up the tasks. They called themselves “Lucy’s Angels.” Because they spread the work over so many hands, no one felt overburdened or resentful.

Lucy’s case may be extreme, but it’s not unusual. In five of six countries for which data were available (Finland, the Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.), researchers found that elderly women (but not men) who never married and have no children are especially likely to have expansive support networks.9 In that study, Australia was the exception. But in another study of 73- to 78-year-old Australians, never-married childless women regularly participated in social groups and were more likely to volunteer than those who were or had previously been married.10

Perhaps because the experience is often anything but isolating, many elderly singles choose to stay single. As sociologist Eric Klinenberg points out in his book Going Solo, in the U.S., only 2 percent of widows and 20 percent of widowers ages 65 and older remarry. Sure, they may have fewer available partners. But many of them aren’t keen to find a new one. Eighteen months after a spouse’s death, only 1 in 6 elderly women say they want to marry again, according to research by Rutgers University sociologist Deborah Carr. For elderly men, the rate is 1 in 4, but if they have a lot of friends, they’re just as unlikely to want to remarry as women. “Their friendships may provide at least some of the desired aspects of a romantic relationship,” Carr writes.

Friends, in other words, can be family too.

In researching my book How We Live Now, I traveled the country talking to people like Dan and Lucy about the people and domestic spaces most important to them. I met single mothers who live together and share the burdens and joys of child rearing. I met elderly friends who share a home as well as meals, chores, and stories—Golden Girls style. I met committed couples who choose to live apart; parents who partnered to raise kids but keep their own relationship platonic; and a single mom whose daughter has 12 Godparents.

Family has become a do-it-yourself kit. Or, as the late German sociologist Ulrich Beck put it: “Marriage can be subtracted from sexuality, and that in turn from parenthood; parenthood can be multiplied by divorce; and the whole thing can be divided by living together or apart, and raised to a higher power by the possibility of multiple residences and the ever-present potentiality of taking back decisions.”

Americans are freer than they’ve ever been to choose the life path that suits them—a change that is reflected in our language. When Patricia Greenfield, a scholar at the University of California Los Angeles, analyzed more than 1 million books published in the past two centuries, she found that over time, use of the word “obliged” fell while use of the word “choose” rose. Similarly, instances of “authority,” “obedience,” and “belonging” decreased while mentions of “individual,” “self,” and “unique” became more commonplace.11

It’s not just singles who are leading the charge. Even traditionally coupled people are living more independently than they once did. A study comparing marriages in 2000 with those in 1980 found that millennial spouses were less likely to eat together, do chores together, go out for fun together, and have as many mutual friends as did spouses 20 years earlier.12 Today’s couples often have separate phones, computers, and online accounts. Although their social networks may overlap, they are unique.

This setup may seem unromantic. But as with singlehood, there may be benefits to pursuing a wider-ranging social life.

In their book Rethinking Friendship, British sociologists Liz Spencer and Ray Pahl describe an especially intense form of traditional family living they call the “partner-based personal community.” A coupled person’s partner, they write, “is the focal point of the person’s social world, acting as confidant, provider of emotional and practical support, and constant companion.” Spencer and Pahl have found that, when compared with those who let more people into their inner circles, partner-based couplers have poorer mental health. Other research suggests that people who rely on multiple friends and family members for emotional support (cheering up, celebrating, commiserating) are more satisfied with their lives than people who lean on just one person.13

Not everyone I met during my travels had as many enduring relationships or was as happy as Dan and Lucy. Just as there were miserable and lonely and self-absorbed people who lived in 20th-century marriages and nuclear families, there will be miserable and lonely and self-absorbed people who live in 21st-century “families of choice.” What’s compelling about this new model, however, is that it is yielding a society that is arguably more fluid, more interconnected, and more adaptable.

As networked individuals, we have the freedom to design the community we want to live in. And if what we choose isn’t working for us, we can always try something else.

Bella DePaulo is a project scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara studying the social psychology of singles. The author of more than 100 scholarly publications, she also writes the Living Single blog at Psychology Today and the Single at Heart blog at Psych Central. Her newest book, How We Live Now: Redefining Home and Family in the 21st Century, was published in August 2015.

References

1. Scanzoni, J. From the normal family to alternate families to the quest for diversity with interdependence. Journal of Family Issues 22, 688-710 (2001).

2. Jamieson, L. & Simpson, R. Living Alone: Globalization, Identity and Belonging Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY (2013).

3. Kposowa, Augustine J. Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 54, 254-261 (2000).

4. DePaulo, B.M. & Morris, W.L. Singles in society and in science. Psychological Inquiry 16, 57–83 (2005).

5. Gerstel, N. & Sarkisian, N. Marriage: The good, the bad, and the greedy. Contexts 5, 16–21 (2006).

6. Klinenberg, E. Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone Penguin Books, New York, NY (2013).

7. DePaulo, B. Singled Out: How Singles Are Stereotyped, Stigmatized, and Ignored, and Still Live Happily Ever After St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY (2006).

8. Musick, K. & Bumpass, L. Reexamining the case for marriage: Union formation and changes in well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family 74, 1–18 (2012).

9. Wenger, G.C., Dykstra, P.A., Melkas, T., & Knipscheer, K.C. P. M. Social embeddedness and late-life parenthood: Community activity, close ties, and support networks. Journal of Family Issues 28, 1419-1456 (2007).

10. Cwikel, J., Gramotnev, H., & Lee, C. Never-married childless women in Australia: Health and social circumstances in older age. Social Science & Medicine 62, 1991-2001 (2006).

11. Greenfield, P.M. The changing psychology of culture from 1800 through 2000. Psychological Science 24, 1722–1731 (2013).

12. Amato, P.R., Booth, A., Johnson, D.R., & Rogers, S.J. Alone Together: How Marriage in America Is Changing Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (2007).

13. Cheung, E.O., Gardner, W.L., & Anderson, J.F. Emotionships: Examining people’s emotion-regulation relationships and their consequences for well-being. Social and Personality Science 6, 407-414 (2015).