Kishan Munroe says the ocean is in his blood. After all, he was born, grew up, and lives on The Bahamas, an archipelago surrounded by the sea. One school was right on the beach. “I’d walk to school and the wind would almost pick you up,” says the amiable and candid Munroe in a recent interview. “I could feel the water, I could taste the salt in it, I could hear it beat against the window of my classroom. I can’t remember any singular interaction with the ocean because that would be like asking, ‘What was the first thing you ever saw?’ The ocean was always there.”

It wasn’t until Munroe began exploring the world on his own, though, determined to meet and interact with people of other cultures, that he realized the depth of his connection with the ocean and his homeland. “When I was traveling, and all these things were happening to me, I felt the sea started coming out of me,” Munroe says. “I felt this need not only to explore but to educate, this yearning for intervention. Historically, Bahamians have always been exploring. We’ve always been traveling beyond, over the horizon.”

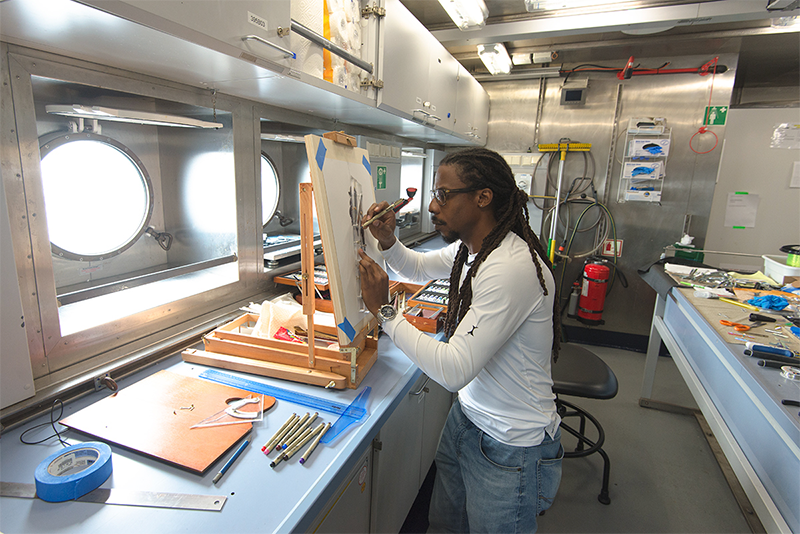

After graduating from Savannah College of Art and Design, Munroe backpacked across the Americas. Later, with a growing resumé of gallery and museum shows for his paintings and mixed-media works, he traveled farther afield, embarked on a lifelong art project he calls “The Universal Human Experience.” In 2019, Munroe traveled up the Pacific Ocean, from Mexico to Oregon, on a 270-foot ship, the Falkor, devoted to ocean research, sponsored by the nonprofit organization, Schmidt Ocean Institute.

The work that Munroe created on the Falkor is on display this month, from March 16 to March 20, at the Explorers Club in New York City. Munroe’s work is featured with paintings and multimedia works by other artists who spent time aboard the Falkor. The artists are fellows in the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Artists at Sea program, the brainchild of institute cofounder Wendy Schmidt. Explains Carlie Wiener, the institute’s director of communications, “We thought artists could make the science more approachable to the public and create new interest in the science and data with imaginative and interactive components.” Nautilus is hosting the show at the Explorers Club. (You can see the works created by the Artists at Sea here.)

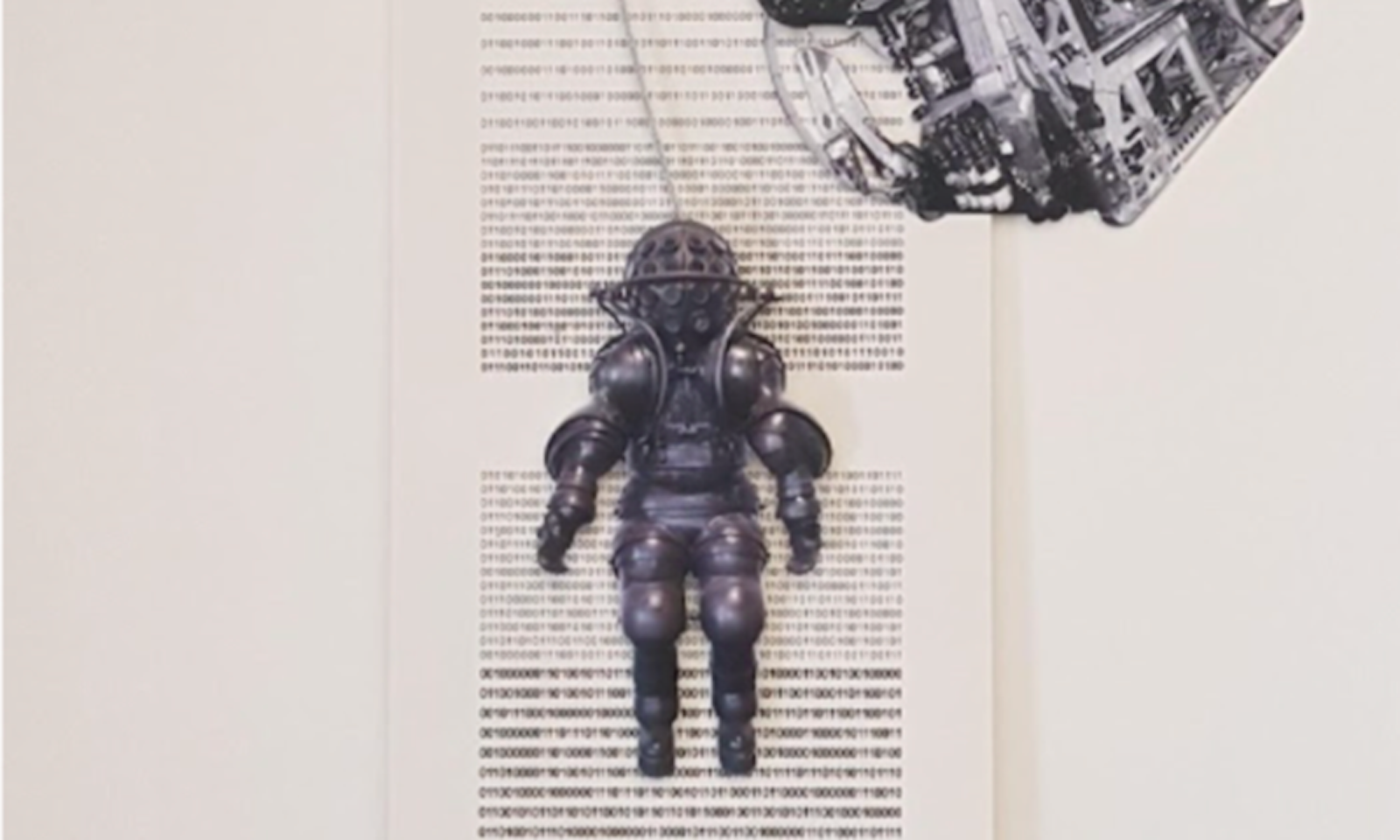

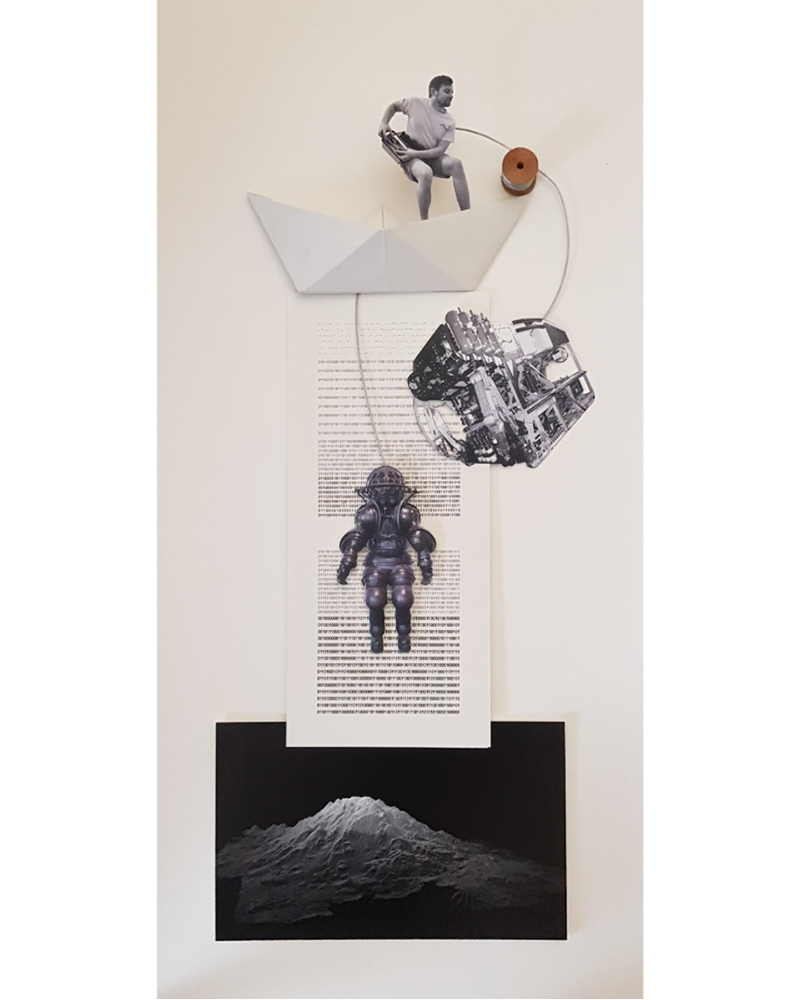

Munroe titled the work he created on the Falkor, made of paper, wire, wood ink, and graphite, “Fathoming Evolutions of Oceanography -1.” On his leg of the journey up the Pacific Ocean, technicians were echo-mapping the sea floor, which Munroe transformed into an image in the work. The ship is named after the dragon, Falkor, in the novel and subsequent movie, The Neverending Story. Falkor helps the story’s boy hero, Bastian Balthazar Bux, save the land of Fantastica from the evil entity The Nothing; his final salvation comes from the Water of Life. The Schmidt institute named its remote undersea vessel, also seen in Munroe’s work, the SuBastian, after the character. Just being on the Falkor, Munroe says, was a revelation. “It gave me a great understanding of the fusion of art and science. Everywhere, on each floor of the ship, you either had text from The Neverending Story or you had artwork from previous artist-residents. It created a wonderful transdisciplinary environment.”

Munroe says his Falkor work is another chapter in his fascination with history, particularly of his homeland. In 2013, Munroe was the youngest artist from The Bahamas to have a show mounted at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas. It centered on a critical incident in modern Caribbean history. In 1980, the year Munroe was born, Cuban jet fighters attacked a Bahamian military ship, the Flamingo, which had arrested two Cuban fishermen who had traversed into Bahamian waters. Four Marine Seaman from The Bahamas were killed. Munroe created a series of richly colored, powerful paintings of the attack. The show, Swan Song of the Flamingo, included his photos and video interviews with military and government officials, from both The Bahamas and Cuba, associated with the incident. Munroe also recruited multidisciplinary artists from The Bahamas and Cuba to fill out the exhibition.

Learning about the Flamingo incident, Munroe says, widened his perspective of the ocean. “I began to understand and respect it in a different way,” he says. “I realized that I wasn’t only documenting the conflict, but the importance of the sea. All of this started over conservation. Whose fish are these? It happened because of a lack of demarcation. ‘You’re in my waters, but where do my waters end? Where do international waters begin? Where does Cuba begin?’ All of that is a part of oceanography now, as we speak about climate change and its adverse effects, especially in The Bahamas, where we are one of the nations most at risk to sea-level rise.”

“Fathoming Evolutions of Oceanography -1” is a collage of Munroe’s global and local perspectives. It’s also a personal work. “I grew up playing with paper boats and planes,” he says. “And those are very temporal. You could always throw them away. It’s the same with art. You can roll it up and move on to another idea, maybe a bad idea, maybe a fresh idea.” The paper boat in “Fathoming Evolutions of Oceanography -1” is “literally my experience,” Munroe says. “The paper boat is my imagination. It represents the thought process, the freedom, the whimsical nature at times of creation. The same for the binary code in it. It represents the layering of data that we face today.”

Ultimately, “Fathoming Evolutions of Oceanography -1” can be seen as a summary of Munroe’s art, his devotion to history, inquiry, conservation, imagination—at least at this port on his journey. Like the best art, it alludes to worlds beneath its surface. “Something is simple until you start peeling away the layers, and then you realize, OK, it’s very complex,” Munroe says. “Art and science are the same way. They have always gone hand-in-hand in exploration.” ![]()