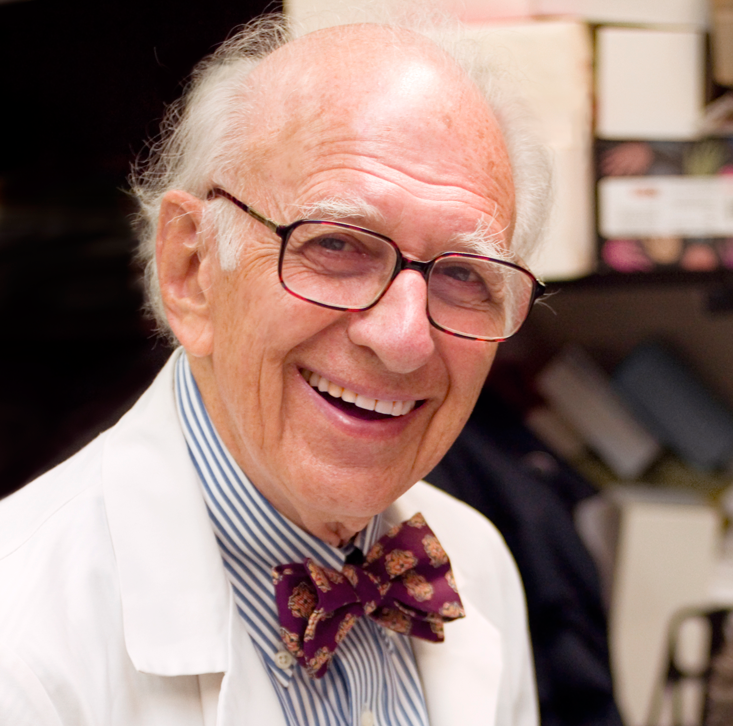

The neuroscientist was in the art gallery and there were many things to learn. So Eric Kandel excitedly guided me through the bright lobby of the Neue Galerie New York, a museum of fin de siècle Austrian and German art, located in a Beaux-Art mansion, across from Central Park. The Nobel laureate was dressed in a dark blue suit with white pinstripes and red bowtie. I was dressed, well, less elegantly.

Since winning a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2000, for uncovering the electrochemical mechanisms of memory, Kandel had been thinking about art. In 2012 and 2016, respectively, he published The Age of Insight and Reductionism in Art and Brain Science, both of which could be called This Is Your Brain on Art. The Age of Insight detailed the rise of neuroscience out of the medical culture that surrounded Sigmund Freud, and focused on Gustav Klimt and his artistic disciples Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele, whose paintings mirrored the age’s brazen ideas about primal desires smoldering beneath conscious control.

I’d invited Kandel to meet me at the Neue Galerie because it was the premier American home of original works by Klimt, Kokoschka, and Schiele. It was 2014 when we met and I had long been reading about neuroaesthetics, a newish school in neuroscience, and a foundation of The Age of Insight, where brain computation was enlisted to explain why and what in art turned us on. I was anxious to hear Kandel expound on how neuroscience could enrich art, as he had written, though I also came with a handful of doubts.

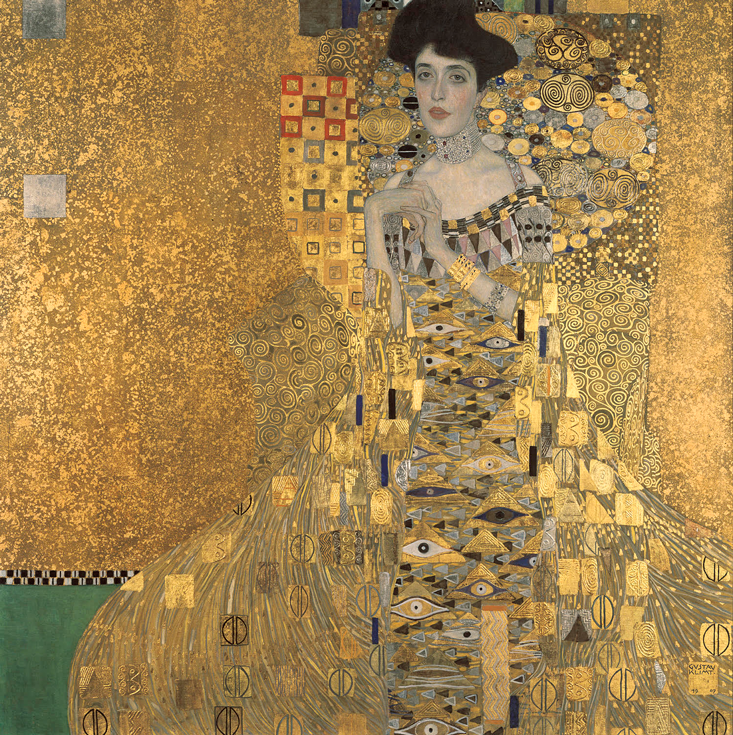

Kandel and I made our way up a spiral marble staircase and into a dark wood and white marble parlor on the second floor. Woman in Gold, Klimt’s portrait of maverick Vienna socialite Adele Bloch-Bauer—its official title is Adele Bloch-Bauer I—commanded the grand room like a film star, a cynosure of odd beauty. We took a seat on a bench and stared.

Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907

Oil, silver, and gold on canvas

Neue Galerie New York. Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund

There she was in her lavish gold gown, filigreed with ovoid shapes—eyes, eggs, fish—blended into a golden background of circles, spirals, and squares.

“The gown is extremely unusual because it’s decorated in all kinds of symbols,” Kandel said. “And do you know what they mean?”

“I think they’re sexual,” I said.

“And where did you get that from?”

“I got it from your book.”

“That’s right,” Kandel said, smiling. “Klimt was fascinated with science. He began to look in a microscope and became fascinated with cells, with sperm and eggs, and incorporated them into his paintings.”

But the painting’s fertility symbols were only foreplay. “We’re attracted to the painting because of the symbols, the gold, but it’s Adele’s face that really draws us into it,” Kandel said.

Indeed, Adele’s cabaret white face, with pink cheeks and big oval eyes, hovered above the golden tapestry with a sly supplication.

“Our visual senses are tremendously specialized for faces,” Kandel said. “This is the point Darwin made: The face is the most important visual image we ever encounter. We recognize other people, we recognize ourselves, by faces.”

Kandel spoke like a 19th-century intellectual who loved to explain, a Freud for the neuroscience age, though with more charm than pedantry.

He continued. The inferior temporal cortex, the brain’s assembly room of perception, has six subsystems specialized for faces, each one with a distinct task. Some processed the geometric shape of a face while others determined its orientation; notably, whether it was upright. Because the entire brain was interconnected, activity in facial neurons put neurons responsible for emotions on alert. As a result, Kandel said, Adele’s face had us asking, “What is her expression? She’s sitting on that golden throne and talking directly to us. What’s she saying? She presents us with the same ambiguity as the Mona Lisa.” An ambiguity that our brains had to resolve.

The purpose of a scientific approach to art is not to take the mystery out of the art. It’s to give you new insight into why you think it’s so wonderful and mysterious.

The neurochemical charge of Adele’s face could be as powerful as love, Kandel said. It could even help explain how the famous painting got to New York. Ronald Lauder, 74, the cosmetic heir and cofounder of the Neue Galerie, fell in love with Woman in Gold when he was a teenager and bought it for $135 million in 2006—at the time, the most ever paid for a painting. When you look at Adele’s face, Lauder has said, “you see a sensuous woman looking at you, feeling, reacting to you, you feel her emotion, you feel her sexuality.”

When Lauder gazed at Adele, Kandel said, his “ventral tegmental area,” where the neurotransmitter dopamine, a key chemical in stimulating pleasure, is manufactured, sprang to action. “The dopamine system gets activated by primary rewards like food and sex, by addiction, by romantic love, and by the love of art,” Kandel said. “If you show somebody a picture of their loved one, it gets the dopamine system going. If you’re rejected in a love relationship, it drives the system even more. So Ronald Lauder falls in love with the painting, goes to see it every year, but can’t get the thing. This is driving him crazy, his dopamine system is going off the charts. It was so active he would have paid $140 million for the painting!”

Kandel smiled. He said he didn’t know exactly what was going on in the tycoon when he looked at Adele. He’s never scanned his brain. But if Lauder can fall prey to the siren call of Woman in Gold, so could we. “Because the painting may have had this effect on Lauder, and we all have the same anatomy, the implication is there must be something special in the art to set off the physiological triggers of attraction and love,” Kandel explained. “And so we say, ‘What a great painting.’”

I told Kandel the painting didn’t trigger such love in me. Surprisingly, he felt the same way. He preferred Klimt’s painting Judith I, which depicts the biblical Jewish heroine, mostly naked, holding the severed head of Holofernes, leader of the enemy Babylon-Assyrian forces, whom she seduced and decapitated. “This is usually depicted as a painful act for Judith, which she did out of altruism,” Kandel said. “With Klimt it’s pure hedonic sexuality.” In fact, Kandel said, because Judith I sparked “a fascinating swirl of emotions,” it was influential in setting him off to explore “what we know biologically about the perception of art, the empathy of art, and the emotional response to it.”

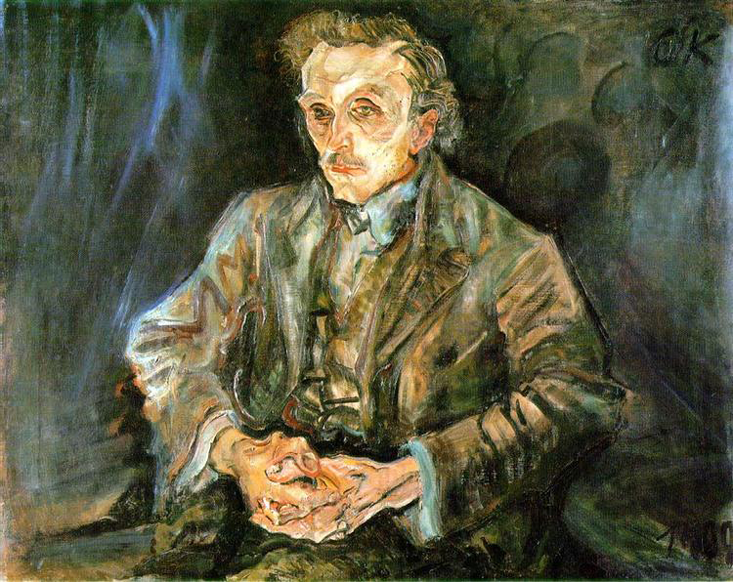

We stood up and walked along the dark wooden walls and came to rest in a corner of gloom. Before us was a painting by the mercurial Kokoschka. Like Klimt, Kokoschka was obsessed with medical renderings of the human body. With slashing brushstrokes of dark green and brown, Kokoschka, in a portrait of Austrian architect Adolf Loos, plumbed viewers into melancholy.

“This is not a pretty portrait,” Kandel said. “The guy doesn’t look particularly handsome. The eyes are not symmetrical. The hand position is extremely awkward.” The distorted features, Kandel explained, captured “a new internal reality—the psychic conflicts of the sitter and the tortured self-inquiry of the artist.”

Adolf Loos, 1909

Oil on canvas

Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin, Germany

At the turn of the 20th century, Kandel said, art that captured people’s internal realities mirrored what scientists were seeing in the lab. Neurologists were learning the brain was a factory of many floors, each with its own function. This one processed language, this one limb movements, this one emotions. While evolution fashioned each neural system to carry out the same function using the same electrochemistry, the interaction of them produced individual thoughts and responses. Myriad environments, after all, presented manifold challenges.

Take the visual system, Kandel said. Everybody’s works the same. The lens of the eye projects a two-dimensional image onto the retina, a sheet of cells on the back of the eye. Retinal cells transmit the image information (essentially lines and contours), converted into neural circuits, along an optic nerve to the thalamus, a region of cells in the mid-brain. The thalamus relays the circuits to the primary visual cortex, which acts like a post office and distributes the circuits to destinations that include the amygdala (center of emotion), the hippocampus (key to memory formation), and the cerebral cortex, which regulates circuits from throughout the brain. This “bottom-up process,” Kandel said, was universal. But it explains only half of what’s going on when we look at art.

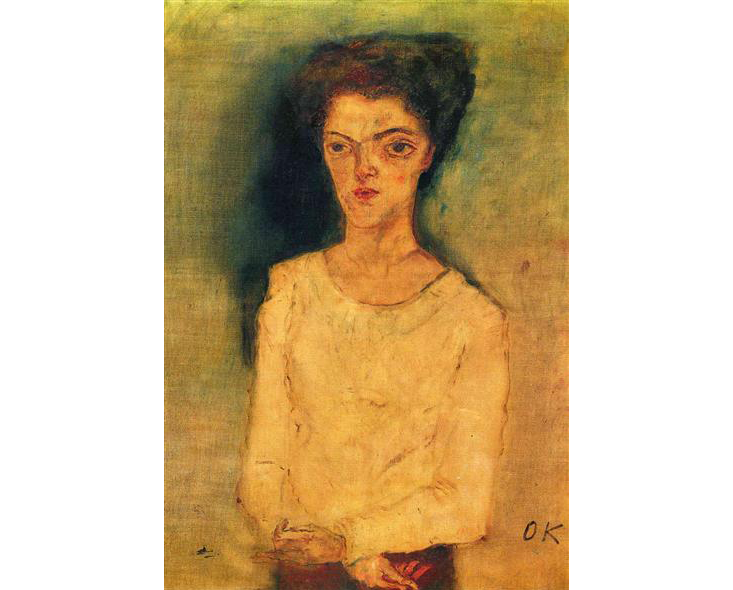

Kandel and I came to a halt in front of another Kokoschka painting, Martha Hirsch (Dreaming Woman), a pale introvert, painted in wan yellows, lounging in a Viennese café or a mental asylum. It wasn’t hard to imagine either.

This is where the other half of brain function, the “top-down process,” was apparent, Kandel said. We filled out the painting with the story that resonated with us individually.

“Go back to the bottom-up process for a moment,” he said. Along every step of the way, neural circuits are being rewired, constructing visual images. Seeing, Kandel stressed, isn’t a matter of our brain working like a camera, freezing images in our head. It’s an act of assembly with numerous brain areas contributing their part. But the bottom-up process alone can’t resolve the anarchy of information that vision sends pouring into our brains. So a top-down process, directed by “executive powers” in the prefrontal cortex, synthesizes neural circuits and restores order. On the brain’s assembly line, memories serve as guides to visual resolution.

Martha Hirsch (Dreaming Woman), 1909

Oil on canvas

Kandel held his eyes on Kokoschka’s dreaming woman. “Top-down processing accounts for the fact that you and I can look at this painting and have a different response,” he said. “That’s because we’re reconstructing the whole thing. We all have different experiences, interact with different people, and have different lifestyles. So we all have a slightly different brain.”

In The Age of Insight, he wrote, “This distinctive modification of brain architecture, along with our distinctive genetic makeup, constitutes the biological basis for the expression of individuality. It also accounts for differences in how we respond to art.”

Kandel and I continued to stroll along the gallery’s dark oak floors. I asked him about his past. Did his own life color his appreciation of art. “Of course,” he said. He got into neuroscience, and later neuroaesthetics, because he wanted to make sense of his past.

Kandel was born in a Jewish family in Vienna in 1929. When he was nine, Nazi Germany, under Hitler’s command, annexed Austria. Amid their murder and exile of Jewish citizens, Nazi soldiers ransacked the homes of Jewish families. They invaded Kandel’s apartment and stole everything of value: jewelry, silverware, and his favorite toy, a battery-powered car. His father, who owned a toy store, was incarcerated by Nazis for months and won his release because he was able to prove he had fought for Germany during World War I. Kandel’s parents sent him and his brother to live in New York with grandparents in 1939, joining them six months later.

“Although my family and I lived under the Nazi regime for only a year, the bewilderment, poverty, humiliation, and fear I experienced that last year in Vienna made it a defining period of my life,” Kandel wrote in his autobiography, In Search of Memory.

The same year Nazis raided Kandel’s home, they stole Woman in Gold from the Vienna mansion of Adele’s widow, Ferdinand, a sugar-industry magnate, who had fled to Switzerland. (Adele died in 1925, at age 43, from meningitis.) In her 2012 book, The Lady in Gold, journalist Anne-Marie O’Connor breathed new life into Adele’s family members and close friends who were imprisoned, raped, or marched to death camps. Under Hitler’s reign, O’Connor revealed, Nazi officers twisted the Woman in Gold into an instrument of Nazi propaganda. When the Nazi governor of Vienna exhibited the portrait in 1943 at a downtown art show, he stripped Adele of her Jewish provenance and renamed the painting Portrait of a Lady with Gold Background. “Adele symbolized one of the most brilliant moments in time, but also one of the world’s greatest thefts: of all that was lost when one woman and an entire people were stripped of their identity, their dignity, and their lives,” O’Connor wrote.

Kandel and I stopped in front of a Kokoschka portrait of Austrian merchant Emil Lowenbach, a sad aristocrat with cavernous eyes. “I got interested in what happened in Vienna in the early 1900s because I wanted to understand how people could listen to Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven one day and beat me up, beat up the Jews, the next,” Kandel said. “Getting kicked out of Vienna was like post-traumatic stress disorder. You want to come to grips with it. And one way to do it is to master it.”

Kandel majored in modern European history and literature at Harvard, determined to understand the contradictory passions of people. His girlfriend at the time, Anna Kris, was another émigré from Vienna. Her father, Ernst Kris, a psychoanalyst in Freud’s circle, convinced Kandel to change course. “He told me, if you think intellectual history is going to lead you this way, you’re completely wrong,” Kandel said. “The only way you can do it is through the mind. So I dropped everything and went to medical school to become an analyst. In addition to getting psychiatric training, I also took neurobiology.”

Kandel said he was greatly influenced by Kris’ writings about art. “He said no painting is complete unless you have somebody paint it and somebody respond to it,” Kandel said. “He pointed out the ‘beholder’ is undergoing a creative experience that recapitulates what the artist is doing. Obviously it’s a much greater creative experience to create it in the first place than to respond to it. But nonetheless looking at a work of art is a creative experience—and the creative experience is pleasurable in itself. And each of us brings our own creative process. Our top-down processes are different.”

Seeing isn’t a matter of our brain working like a camera, freezing images in our head. It’s an act of assembly.

It was fascinating, I said to Kandel, to reflect on how the architecture of our brains, constructed from our individual genes, experiences, and memories, shaped our view of art. Beauty was in the brain of the beholder. But I still wasn’t quite clear on how neuroscience enhanced our appreciation of art itself. If art was an external stimulus, indistinguishable from any other, what was special about it? In fact, by reducing our experience of art solely to brain chemistry, weren’t we creating a new kind of night school in art depreciation?

Kandel laughed. “This is what many humanists are concerned with,” he said. “They think these heathen scientists are going to come along and provide a little bit of visual, biological insight into art, and this is going to replace the aesthetic response. That’s not my feeling at all. The purpose of a scientific approach to art is not to take the mystery out of the art. It’s to give you new insight into why you think it’s so wonderful and mysterious. If we had a detailed understanding of sexual activity, knew exactly which regions of the brain were involved when each of us had an orgasm, would it reduce the pleasure of having sex? No. It would give you additional insights that might give you additional approaches. But it wouldn’t alter the basic experience. This is the same thing. This is an aid to greater understanding.”

Art, too, engaged us in the world and lives of others like nothing else, Kandel said. Semir Zeki, a British neurobiologist and vision expert, the pioneer of neuroaesthetics, had written that the main function of the brain was to acquire knowledge about the world. Art was a special form of knowledge because it engaged the brain’s full orchestra of neural systems. “Since art arouses emotion, and emotion elicits both cognitive and physiological responses in the observer, art is capable of producing a whole-body response,” Kandel explained.

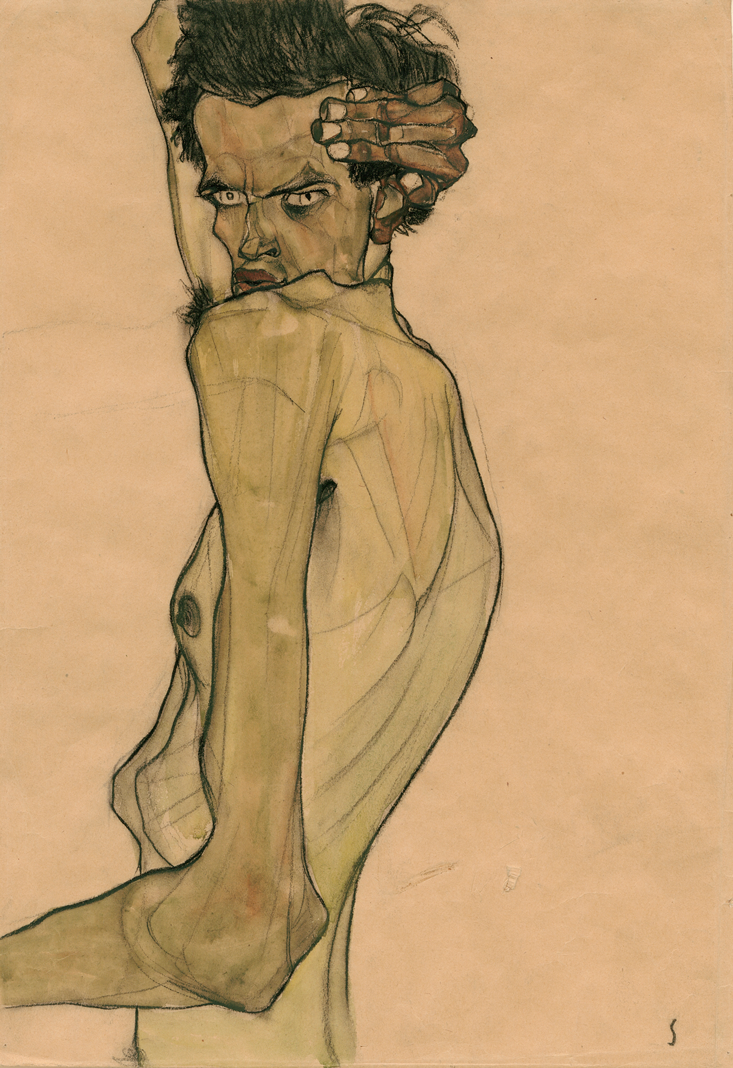

Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted above Head, 1910

Watercolor and charcoal on paper

Private Collection

We stopped in front of a painting by another Austrian in Klimt’s circle, Egon Schiele. It was a self-portrait by the saturnine artist, who died from Spanish flu at age 28. Schiele was standing naked in profile, his right arm twisted around his head. With charcoal lines and elemental watercolors in brown hues, Schiele pictured himself as gaunt and angular, bones stretching his skin, a look of recrimination frozen on his face.

“I think this is a damn interesting painting,” Kandel said. “The guy looks like he’s on the verge of a breakdown. This is the existential anxiety of modern man. Austria is about to go to war. This is a terrible burden. But you see no overt reference to war. It’s in the body and face.”

At base, Kandel said, the Schiele painting was a story, and stories inspired us, as they did our earliest ancestors, to envision another way of life. “Art allows us to see aspects of the world we’ve never seen or experienced, feel emotions we’ve never felt, see beauty we’ve never seen, love women who would never love us. It creates a fantasy life for us,” he said, smiling. “And we all live by fantasy.”

Kandel and I made our way back to Woman in Gold and took a seat. We discussed it with a renewed perspective. “I’ve seen this painting dozens of times, but each time I’m more aware of the decoration in one corner or elements I’ve either ignored or forgotten,” Kandel said. It’s a biological verity of perception, he added, that you can focus on only one thing at a time. “As a result, you’re filling in the painting by looking. This is wonderful. This shows how your imagination, your creativity, works.”

As we recreated the Woman in Gold in our minds, Kandel said, there was another element at work. In the process of seeking visual and emotional resolution, our brains engaged our knowledge of the world and art. During his lifelong research into memory, Kandel had written extensively about the neurochemistry of learning, how learning “can significantly increase the number of synaptic contacts between the nerve cells,” potentially expanding our capacities to think and feel. “Our experience of a painting is not determined simply by the image that we see in front of us, but also by the history of the image and everything we know about it,” he said.

It was now my turn to share what moved me most about Woman in Gold—which indeed stemmed from everything I knew about the painting and Klimt. Adele, unlike her Victorian sister, Therese, fled the parlors of high society for Vienna’s demimonde of artists and intellectuals. At the time, Klimt’s talents were in full bloom, but he was working in a vale of resignation. A swaggering bear of a man, Klimt lived to upend Austria’s ruling class. His works spirited away mythical Greek goddesses to assail conventional morality and expose desire gone wild. In 1894 he was commissioned by Austria’s Ministry of Culture to create three ceiling paintings at the University of Vienna on the theme, “The triumph of light over darkness.” Klimt’s paintings, Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence, were phantasmagorias of naked bodies, a giant octopus, skeletons, and priestesses, floating in a cosmic firmament. Austrian authorities expected the murals to spread the light of human reason over the darkness of chaotic nature. When they saw the opposite, they refused to exhibit them.

Klimt was disgusted. “Enough of censorship,” he sniped to his friend Berta Zuckerkandl, a writer who hosted Vienna’s avant-garde literary salon. “I want to get out.” Klimt’s remarks were noted by Carl Schorske in Fin-De-Siecle Vienna, a definitive history of the period. Schorske, director of European Cultural Studies at Princeton University for many years, who died in 2015, wrote the depth of Klimt’s dejection was expressed in his art. Klimt underwent a “reshuffling of the self,” Schorske wrote. In his previous public works, Klimt raged against repression. “Now he shrank back to the private sphere to become painter and decorator for Vienna’s refined haut monde.”

The narrative of a political artist whose public defeat caused him to withdraw into a private utopia struck a deep emotional chord in me. I don’t know why exactly. The heroic drive of the rebel in search of naked truths has always been an emotional rush for me—in art and science. And so the rebel’s invariable failure fills me with pathos. I didn’t grow up during the horrors of World War II, as Kandel did, but at the end of the postwar baby boom in suburban California, stifling in its own right, at least to me. Still, I shared with Kandel the transcendent power of Klimt’s work, even though we each saw it in the studios of our own minds.

Before I met Kandel at the Neue Galerie, I tended to side with critics, from both the sciences and arts, who had written neuroaesthetics portrayed the experience of art as little more than a “programmed response of brain circuitry,” as one critic said of Kandel’s The Age of Insight, and ignored the social and cultural factors that influenced our appreciation and understanding of art. My afternoon in the gallery with Kandel had shown me quite the opposite.

As much or more than any painting in history, Woman in Gold symbolized how art was affected by social and cultural factors that forever shaped our brains, emotions, and perspectives. Knowledge was such a powerful elixir when looking at Woman in Gold. The 2015 release of Woman in Gold, a film about the restitution of the painting to Adele’s niece, Maria Altmann, of Los Angeles, introduced the painting to a new mainstream audience. Knowledge of the emotional story helped the 2015 exhibition, “Gustav Klimt and Adele Bloch-Bauer: The Woman in Gold,” to be among the Neue Galerie’s most popular ever.

I had felt, too, neuroscience was anesthetizing art like a specimen upon a lab table. But looking at the paintings with Kandel drew me closer to them. The importance of art, he told me, was its power to reflect who we were and what we cared about. It showed us we evolved to learn, connect with others, and change.

As we got up to leave, Kandel made a suggestion. “Walk back and forth in front of Adele. Her eyes follow you. That’s the magic here.” Kandel was referring to our visual systems converting Klimt’s two-dimensional image into a three-dimensional portrait in our minds. But I felt he was talking about much more. Adele was looking into us from Klimt’s private studio, her eyes evoking an endless sorrow. It was a deeply personal experience that felt like a universal one. Art, the scientist showed me, was our portal into the world.

Kevin Berger is Nautilus’ features editor.