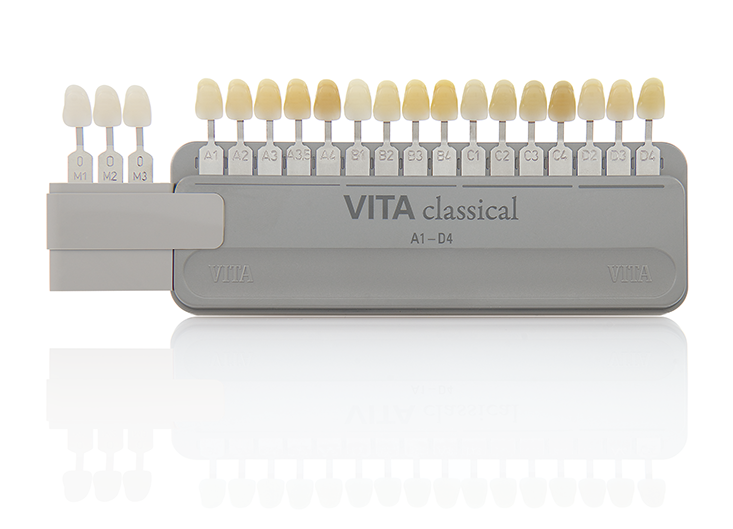

Ronald Perry can’t seem to get his patients’ teeth white enough. The Massachusetts dentist, who directs the Gavel Center for Restorative Research at Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, shows patients who want to whiten their teeth the VITA Classical Shade Guide with Bleached Shades, which presents a total of 19 dark and light shades. They invariably go for the whitest, rather than a creamy ivory, a more natural shade he favors.

As teeth-whitening procedures have become more widespread, our very definition of white has changed. “What was once considered natural white is now yellow to people,” Perry says. The bleached shades were added to the VITA guides several years ago to keep up. “Sometimes there’s really not a shade I can pick that’s white enough,” says Perry of his patients, who sometimes show up with photos of celebrities with gleaming smiles. “They really want a monochromatic white, like Chiclets.” Perry has coined his own term for the shade people want: “TB1: Toilet-bowl white.”

Almost all whitening products contain the same active ingredient, either carbamide peroxide or hydrogen peroxide. It penetrates the microscopic pores in the enamel that coats your teeth, producing oxygen molecules that react with and break apart the grime-causing compounds. Perry shines an LED lamp on the teeth to speed up the chemical reaction (the light also dehydrates your teeth and makes them chalky, so they look temporarily whiter in the mirror afterward). The process is generally safe, but aggressive bleaching can leave teeth sensitive and gums irritated, and some studies suggest it can slightly soften or erode enamel. Bleaching certainly doesn’t make our teeth healthier.

The implications of science often run square against deeply entrenched cultural beliefs and values.

Teeth-bleaching may be the peak of the Western world’s obsession with getting whites whiter. It’s the same impulse we see in our laundry detergents and sparkling consumer products. “In our society, it’s perceived that whiter and brighter is better,” Perry says.

Yet increasingly our obsession with whiteness is clashing with science and medicine, which have begun to question the idea that cleanliness and sterility—the values that give white its symbolic power—are better for our health. Hygiene is critical in certain contexts, like a hospital room, but carrying its power unconsciously into every part of our lives could hurt more than help us.

“Cleaner is better in the presence of a contagion, or an epidemic,” says Michael Zasloff, an immunologist at Georgetown University Medical Center who has studied human-microbe interactions. “But cleaner is not better in respect to your normal health.” There’s growing evidence, often headlined under the “hygiene hypothesis,” that a cleaner, more sanitary lifestyle, and fewer infections, is leading to a rising incidence of allergic and autoimmune disorders.

Maybe this more nuanced understanding of cleanliness and health will start to filter into our daily lives and influence our unconscious choices. Maybe we’ve finally reached peak whiteness.

But history shows us the implications of science often run square against deeply entrenched cultural beliefs and values. And the color white has been woven into our culture as an emblem for everything that’s pure, healthy, and desirable.

White has a physical purity. White light contains roughly equal amounts of every color in the visual spectrum, and activates all three types of cone cells in our eyes related to color. As a result, we perceive materials that don’t absorb color, and reflect light back to us, as achromatic—white.

The union of white and purity in Western culture may have its first roots in religion. That’s how Kathleen Brown, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania, sees it. “Historically, white is one of the ways men of the cloth signified their calling,” Brown says. Later, this association with religious purity evolved into bodily purity. (“Cleanliness is, indeed, next to godliness,” declared John Wesley in an 18th-century sermon.) Brown’s book, Foul Bodies, chronicles cleanliness in Europe beginning with its colonial expansion, and in early America up to the Civil War. Cleanliness, she says, was signified by a growing profusion of white undergarments, worn against the skin beneath the outer clothes, and then spilling forth in ruffled cuffs and collars. The undergarments were seen as having a cleansing power, the stains they collected a sign that they were drawing dirt from the body.

White became an indicator of class and wealth. The richer you were, the finer, whiter, and more intricate were your linens, and wealthy people changed them every day. White underclothes, sheets, towels, and tablecloths were prized for the very fact that they were so hard to keep clean. “It’s the sheer impracticality and difficulty of maintenance that makes it such a genteel object,” Brown says.

One dentist has coined his own term for the shade people want: “TB1: Toilet-bowl white.”

In the 19th and 20th centuries, white was an important color in sanitation movements that swept cities after cholera and influenza outbreaks. Katherine Ashenburg, author of The Dirt on Clean: An Unsanitized History, notes that cleaning products of Westerners changed. “Before that, their soap was really, really disgusting,” she says; it was made of rendered animal fats and came in ugly greens, browns, and grays. Procter & Gamble finally developed an inexpensive white soap that could be sold in bars in 1878. Ashenburg says that Ivory’s white color—which evoked purity and cleanliness—had a lot to do with its success.

“By the 1920s, white was being used as a hygienic aesthetic,” says Virginia Smith, an independent historian and author of Clean: A History of Personal Hygiene and Purity. Doctors donned white coats, and nurses wore starched white hats. Hospitals and clinics were given white walls and white tile floors. There’s a practical reason: White can offer proof of being clean. But this function became intertwined with layers of meaning it acquired over time, Smith says. In the 20th century, white sports clothing became more commonplace, a symbol of health and vigor.

Eventually, whiteness made its way into homes and objects as outward reflections of personal cleanliness. In 1925, the architect Le Corbusier declared in “The Law of Ripolin” (referring to a popular brand of paint) that whitewashed walls had a spiritual and moral cleansing power. Every citizen, he wrote, should “replace his hangings, his damasks, his wall-papers, his stencils, with a plain coat of white ripolin. His home is made clean … Everything is shown as it is. Then comes inner cleanness.”

White’s powerful symbolism, of course, has darker connotations. Brown points out that as European colonists encountered other groups in America and West Africa, there was “a new interest in whiteness both as an indicator that clothes were clean, but also a racial indicator of a kind of refinement and civility.” In portraits of 17th- and 18th-century European settlers, particularly women, faces “start to glow like weird white ghosts,” Brown says, showing their purity as bearers of civilization. In later years, white’s symbolism was appropriated into ideas of racial purity, manifested in Nazi language like “racial hygiene” and Ku Klux Klan garb.

As the 20th century marched on and the cultural meanings of white accumulated, manufacturers made products ever whiter. And science was employed to push the white tide. “Having a really solid white, a really intense white—it’s really an achievement,” explains Paul Messier, a photography conservator in Boston who’s studied the whitening of photographic papers in the 20th century. “It doesn’t just happen; it’s highly engineered.”

The thrust of the engineering, explains Renzo Shamey, a color scientist at North Carolina State University, has been to overcome yellow. Natural materials like wool, cotton, linen, and wood pulp have yellowish tints—so do our teeth. “Psychologically speaking, we associate yellow with dinginess and with dirt, so if a base white is perceived as yellowish white, it is considered dirty,” he says.

There are a few ways to banish yellow. One is by bleaching, which destroys the yellow pigment. Another is by adding a bit of bluish tint. “Bluish white is considered, psychologically speaking, cleaner,” says Shamey. It’s not universal: In some countries, for example, paper is slightly pinkish because whites with red tones are seen as whiter. But in the West, most people see the bluer of two whites as whiter. In dentistry, a product called blue covarine has recently been added to toothpastes to counteract yellow and give the illusion of clean white teeth. “Bluing” clothing with indigo in the wash is a centuries-old strategy to counteract yellow clothing stains in clothing.

Clearly, in the world according to copy paper, social status is marked by ascending levels of whiteness.

But bluing is an imperfect solution; the added color reduces the reflectance of the material, giving it a gray cast. Fluorescent compounds developed in the first half of the 20th century offered a perfect solution. In 1929, a German chemist named Paul Krais soaked fabric in an extract from horse chestnuts, which contained a fluorescent chemical, and noticed that the cloth became whiter and brighter. In the 1930s, chemists began developing similar compounds derived from ultraviolet light-responsive plant chemicals called stilbenes. One of these was introduced to the market by German chemical company IG Farbenindustrie; called Blankophor, it became the first wide-scale commercial optical brightening product. Detergents, soaps, and textiles were one of the earliest markets for optical brighteners. The agents did not last long in clothing, but could be replenished with each wash.

Essentially all optical brighteners use the same trick. They absorb light in the ultraviolet spectrum and emit it back as light in the blue-violet range. The whitening effect is two-fold. The extra bluish light counteracts any yellow present, masking dinginess. It also generates the illusion of new light. Consumer products not only look clean, they become beacons of light. The increasing use of fluorescent brighteners, says Shamey, has “changed our perception.” What was white in the past now looks dingy.

At my local OfficeMax, stacks of copy paper vie to be the whitest, brightest thing in the room. The brighter the paper, promise the companies, the brighter the copied images and colors will be. A scale, from zero to 100, measures the brightness, based on the reflectance of light; the higher the number, the higher the reflectance, aiming for that magic fluorescent sheen. Boise Multi-Use Copy Paper, housed in a drab green package with a rating of 92, seems to exist solely to contrast against the same brand’s Polaris Premium Multipurpose Paper, brightness 97, its cover a blue night sky punctuated by white stars. “The Power of First Impressions,” reads the package of HP Multipurpose Ultra White, with a photo of a young blonde woman holding her slim resume, printed on a gleaming white sheet, brightness 96. They’re all topped by HP’s Laserjet paper, brightness 98. The package features a woman who chats on her cell phone from a private jet. Clearly, in the world according to copy paper, social status is marked by ascending levels of whiteness. I pull a sheet from an opened package and it gleams, crisp and glacial. I bask in its whiter-than-white glow.

What does all this whiteness gain us? Even as our smiles and consumer products have gotten ever-more dazzling, a growing body of scientific research has called the pursuit of purity into question. Our carefully cultivated whites, it implies, could actually be a symbol of wrongheadedness.

At the heart of this shift is a growing awareness about the role of microbes in our health. “Our relationship to microbes has gone through a dramatic, almost revolutionary reorganization over the last 15 or 20 years,” says Zasloff, the Georgetown University immunologist. The discovery of germs as the basis for diseases led to a focus on sanitation. “There was a growing perception that the less you were exposed to microbes, the better,” he says. But increasingly we recognize that every part of our body has evolved to live with microbes, and most of them do us no harm. “We’re a collection of microbes and us,” Zasloff says.

Cleanliness, he adds, is not even possible in the way we like to imagine it is. “To some extent we’re wearing white unconsciously—we think we’re clean. It’s a false message,” Zasloff says. Our bodies can’t be sterilized: microbes are always there. “No matter how white your teeth are, if you were to swab your mouth, there would be large numbers of bacteria,” Zasloff says.

Some studies point to the benefits of being dirty: Children who grow up on farms or are exposed to household pets have lower allergy and asthma rates, for instance, and a recent study found the same effect in infants living in houses with bacteria, pet dander, and roach allergens.

Zasloff is optimistic this science will eventually translate into a cultural shift. “What we’re going to be seeing is the gradual appreciation that we must live in harmony with microbes because they’re part of us,” he says. We may even change our aesthetics: We might see a clean, scrubbed child and worry about her health. White, with its message of pristine sterility, could start to signify an unhealthy disengagement from our environment.

But try issuing that message to Ronald Perry’s patients. “I don’t think there’s an end to it,” says Perry of the pursuit of whiter smiles. The social messages are too strong. “Do you have to have whiter teeth to be functional? No.” But after a bleaching session, he says, his patients “feel better about themselves; they feel more confident.” And that feeling is still worth scrubbing, bleaching, and brightening for.

Courtney Humphries is a writer in Boston who covers science, medicine, architecture, and urban planning.