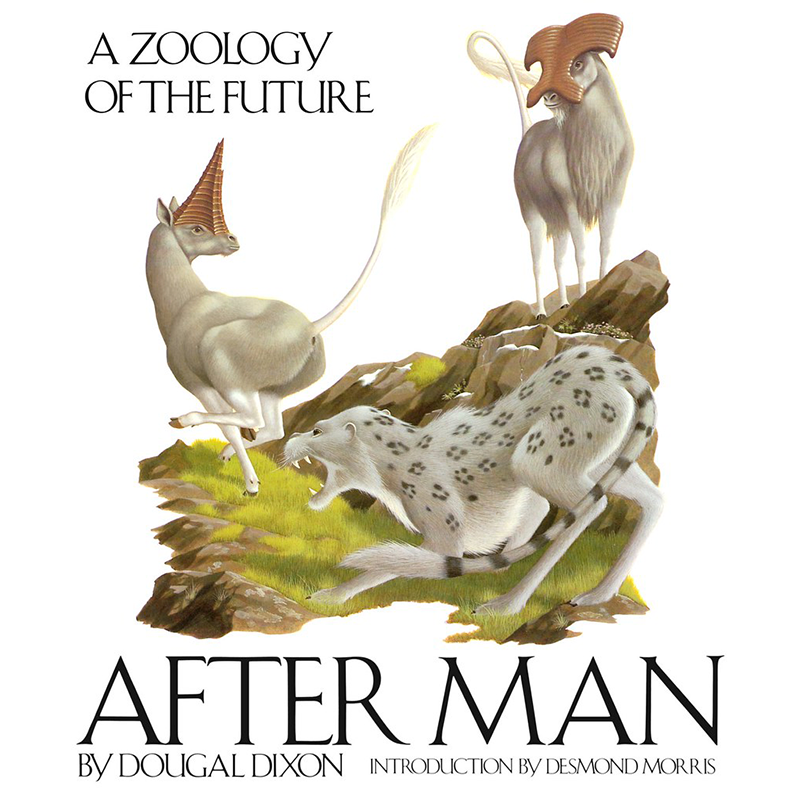

Some 50 million years from now, a long-limbed, long-necked, and long-eared herbivore roams the temperate woods and grasslands of the Northern Continent. The Common Rabbuck (Ungulagus silvicultrix) appears to be a cross between a white tailed deer, a giraffe, and a rabbit. Its natural predator is a wolf-sized muscular rodent with fearsome fangs called the Falanx (Amphimorphodus cynomorphus), which hunts in a pack. In the rainforest canopies in what had once been Africa and Asia, a lean and tall cat called the Striger (Saevitia feliforme) moves through the branches with opposable fingers and prehensile tail.

These are only a few of the dozens of animals that appear in After Man: A Zoology of the Future, Dougal Dixon’s 1981 book that takes readers to the late Cenozoic epoch known as the Posthomic, the era “After Man.” In his introduction to After Man, biologist, author, and TV presenter Desmond Morris would enthuse, “as soon as I saw this book, I wished I had written it.” Nominated for the Hugo Award, and something of a cult classic, After Man would go on to spawn a series of books, a television show, and the discipline of speculative evolution, which combines art, literature, and science to imagine not just how creatures might appear in the future, but how they might have developed in alternate timelines or on other planets.

With the latest report from the International Panel on Climate Change, released in February 2022, it’s time to revisit After Man. According to a New York Times article on the report, the “dangers of climate change are mounting so rapidly that they could soon overwhelm the ability of both nature and humanity to adapt.” In the midst of this apocalyptic state of affairs, it’s worth imagining what a world “after man” might offer. Perhaps After Man can compel us to consider the “long now,” a long-term perspective, and picture what Earth could be like after humans have gone. It’s an exercise in a type of humility that only science can afford.

Dixon, a Scottish paleontologist, didn’t conjure a tale about a time-traveling biologist, or offer an account of humanity’s last days. After Man is mute on the causes of our extinction. Dixon leaves you wondering what did us in as you explore his haunting, imaginary space. With immaculate drawings of imaginary beasts based on Dixon’s notes for a team of illustrators, and the fine calligraphy in the margins, After Man feels as if it were the notebook of a 19th-century naturalist. It makes you grapple with the idea of human extinction in an uncanny manner. The paradoxical or impossible artifact—After Man could only have been written by a human long after humanity’s extinction—offers the “same sense of wonder that we get from contemplating the natural world around us,” said Susannah Lydon, an assistant professor of plant science at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom. “After Man was one of my most treasured books as a small child and it’s fair to say that the ideas are hard-wired into my understanding of the world.”

This sort of storytelling filled a niche that readers didn’t even know was in need of filling.

The book is able to have that impact partly because Dixon based it, he told me in a recent conversation, on the actual “physical and ecological conditions that have driven evolution.” Dixon drew from concepts like convergence and parallel evolution, Cope’s Rule and Bergman’s Rule, mimicry and niche partitioning, island dwarfism and display, parasitism, symbiosis, and commensalism—the “whole gamut of observed biology.” He said, “It was a matter of seeing what works for animals of today, and what we know of what worked for animals in the past. If it worked then, and it works now, it is going to work for animals of the future.”

This sort of storytelling filled a niche that popular science readers didn’t even know was in need of filling, the literary equivalent of Rabbucks evolving and swarming into forests after the extinction of deer. Inspired by After Man, speculative evolution has proliferated in film, literature, and online. In his New York Times-best-selling 2007 book The World Without Us, science journalist Alan Weisman tread the imaginative trail Dixon had blazed. He invites us to envision what would happen if humanity suddenly vanished—what effect our absence would have on both natural and constructed environments. Weisman recounted to me that when his manuscript for The World Without Us was being edited, “someone there who’d worked on After Man sent me a copy because he thought I’d enjoy the illustrations, which of course I did.” Recognizing the pertinence of a kindred project, Weisman included After Man in his book’s bibliography. Both books present science with a creative flourish that’s not necessarily encountered in more staid scholarship.

“The result is speculation built on fact,” Dixon wrote in his introduction to the original edition. “What I offer is not a firm prediction—more an exploration of possibilities.”

And what possibilities! In the jungle, the Striger often stalks a long-armed primate called the Kiffah (Armasenex aedificator). It has red fur and a blueish, weathered face almost pushed into its chest. Its natural defense against the Kiffah is its relative degree of intelligence and sociability. Off the coast of Antarctica, meanwhile, are the aquatic Vortex (Balenornis vivipara), the world’s largest animal at 30 tons and at least 36 meters in length. This whale-like creature—with a massive beak that sieves out the plankton it ingests—is actually a bird, directly descended from the penguins who once swam the frigid waters. Then there are the Night Stalkers (Manambulus perhorridus), their common name true to their status as being among the most terrifying creatures of the Posthomic age. Picture a bipedal, 5-foot-tall bat—compact, with a fur covered body—that appears as if it walks on its arms with its legs swung over its shoulders. Giant sonar where its ears and eyes would be, it gallops and shrieks through the grasslands of the island continent of Batavia.

“I’ve always been a bit of a fantasist,” Dixon told me. “Grew up on the shores of the Solway Firth, between Scotland and England. Beautiful, but many found it bleak and desolate. Despite the beauty of the landscape, when I walked there as a child, I used to imagine myself wandering the shores of a plesiosaur-infested Jurassic lagoon, or the crystalline coastline of a steamy ocean beneath low-hanging ringed moons on an undiscovered planet.”

This is an emotional reaction that many have described when writing about their own experience first reading After Man, not just of wonder, but of wisdom: the awareness that humans have not always been here, and that we won’t always remain. “Speculative biology applies precisely the same principles that researchers use to interpret patterns in the fossil record, and in that sense it’s analytical,” Lydon said. “You’re using evolutionary concepts to move forward from an initial starting point only, rather than attempting to interpret the patterns in a hugely incomplete, hugely biased dataset smeared through deep time.”

An exercise as pedagogical as it is scientific, speculative evolution functions as a type of Gedankenexperiment existing at the nexus of science fiction and fact. “It is a matter of giving fictitious examples of factual processes,” Dixon said. After Man’s operative aesthetic is one of scientific wonder. It reminds us that imagination can be as central as analysis in a scientific endeavor, and that our attraction to the sciences is as poetic and lyrical as they are logical and pragmatic.

In 10 million years, biodiversity will be restored to where it was before the sixth mass extinction.

Dixon’s own career, which had a veritable Cambrian Explosion following the publication of After Man, has engaged a sense of wonder in later books, including The New Dinosaurs, which envisioned a world where non-avian dinosaurs hadn’t gone extinct; Man After Man, which applied the same principles from his most celebrated title to human futures; and Greenworld, a taxonomy of an extraterrestrial planet (so far only released in Japan).

After Man makes the geological concept of “deep time” deeply personal. It takes on what the theologian and philosopher Thomas Berry described as the challenge to “create a new language, even a new sense of what it is to be human … to transcend not only national limitations, but even of species isolation, to enter into the larger community of living species … a completely new sense of reality and value.”

Such deep-time thinking as described in After Man, Berry’s The Dream of the Earth, Stephen Jay Gould’s Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle, and John McPhee’s Basin and Range exists precisely to embody that command of creating a new vocabulary commensurate with the reality of being finite individuals in a nearly infinite cosmos. When wonder is combined with wisdom, tempered perhaps with the anxiety that comes after considering the incomprehensible breadth of deep history far before and beyond the confines of our tiny lives, the resulting emotion is the sublime.

In a critique of After Man, literary scholar Matthew J. Wolf-Meyer castigates what he terms the “nihilism of deep time.” In his book Theory for the World to Come: Speculative Fiction and Apocalyptic Anthropology, he writes that Dixon “supports a damned-if-we-do, damned-if-we-don’t approach to the Anthropocene and catastrophes in general.” This, I think, is a wrongheaded interpretation, for we ask not for whom the bells of deep time toll—they toll for all of us.

Thirteen millennia from now, and the Earth’s axial tilt will shift, altering what seasons occur in which hemisphere; 15,000 years from now and the North African Monsoon shift will convert the Sahara from a desert into a tropical rainforest once again; 50,000 years from now Niagara Falls will have completely eroded away; 2 million years from now and the effects of ocean acidification will be largely reversed, coral reefs having returned. Ten million years into the future and biodiversity will once again be restored to where it was before the sixth mass extinction of the Anthropocene; 80 million years into the future and Hawaii will have completely sunk into the Pacific; in a quarter of a billion years the continents will have coalesced into a new Pangea.

Whether or not we like it, one day there very likely will be a Posthomic age. What After Man inculcates with its readers is the ability to imagine and make peace with this reality, to walk on the proverbial shores of Solway Firth and to appreciate the Plesiosaurs along its banks, and the strange alien moons shining above it. ![]()

Ed Simon is a staff writer at The Millions and contributing writer at Belt Magazine. His most recent books are Pandemonium: A Visual History of Demonology and Binding the Ghost: Theology, Transcendence, and the Mystery of Literature. Follow him on Twitter @WithEdSimon.

Lead photo: BlueLotusArt / Shutterstock