As a pediatric hematology/oncology and palliative care fellow, I face my share of, “How do you do that?” “You must be a special person,” or “That must be so depressing,” comments. Up until this point, I have largely avoided the topic of what I do with my family, especially with my two daughters.

Over the years, the story I tell my children about what I do has changed. My first daughter was born in my fourth year of medical school, my second daughter in my third year of pediatric residency. Medicine, call, and pagers have been part of the fabric of their lives. At first, they would say, “Mommy is a doctor”; as they aged and could understand more, they would say, “Mommy is a pediatrician.”

Somehow, it is easier to explain what Daddy does as a head and neck surgeon. The girls know that he cuts bad things out, that he fixes things. Sometimes he stays late because it takes a long time do an operation. Sometimes he gets called in the middle of the night to take someone back to the operating room. They get it. They eagerly ask to see “guts pictures” when he gets home, and they pore over anatomy books with the vigor of a first-year medical student. We taught them both at about age two how to say “otolaryngologist,” which was more party trick than anatomy lesson. Perhaps unconsciously, we never taught them to say “oncologist.”

“I don’t want him to die, but if he does, then can you tell me his name?”

Most parents worry over how to answer the big questions, from the birds and the bees to why bad things happen, to even curiosity about death. What worried me more was how to tell my children exactly what I do. Death is not a taboo topic in our house. As Catholics, we have a crucifix hanging prominently in our home, and my children have attended funerals. If they ask, we answer. But somehow my job (especially the hospice part of my job) was off-limits.

What is this big part of my life that calls me away, sometimes every fourth night, sometimes every other weekend, on late nights past bedtime, from school events and soccer games? Some days I leave my children home sick to take care of other sick children, children who are not my own but who have been entrusted to me all the same. How do I weigh the importance of my febrile daughter, with a virus caught from day care, and my new patient, with leukemia, in the pediatric intensive care unit with a WBC of 400,000?

As my oldest daughter has grown, so has her understanding of my work. She knows that I work in the hospital and take care of sick children, which is different from the pediatrician she sees, who she calls the checkup doctor. Last year, I had a near miss with this big question after she overheard me answer the phone: “This is Melissa Mark with oncology.” Her question, “What is oncology?” was easily brushed aside and redirected in the hubbub of a busy call night of returning pages in between bedtime stories and tuck-ins.

Then came the day I had to tell her. I was gazing at my precocious six-year-old, fresh out of the bath, independent enough to get ready for bed, pick out PJs, and brush her teeth. I also had one eye on my three-year-old, who was trying to take her turn at the bath. She cautiously stuck one foot in the tub and said, “Too hot, Mama.” Her eyes glowed under blunt, freshly cut bangs. After a snow day and child care issues left me unexpectedly at home, I was reveling in the simple moments of being a mom. I enjoyed pretending to be a stay-at-home mom and even cooked homemade lemon-poppy seed pancakes.

My pager went off, and I was jolted out of my pretend world. It was time to change hats. I turned my attention to one of our hospice nurses who was in the home of a particularly angry and belligerent young man who was fond of the F-word, which I could hear in the background. Absorbed in the conversation, I forgot about those little attentive ears in the next room. I said almost flippantly to the nurse, “Pericardial drain or not, eventually his disease is going to progress, and he will die. We have nothing left to offer. Revoking the DNR doesn’t make sense if he isn’t willing to come back to the hospital.”

I took a moment to soak up the normalcy in my life, knowing all the things that can and do go wrong, wondering when disaster will strike in my own home.

A thoughtful, curious little head popped out of her room, hair still wet and tangled. “Mom, that’s very sad, did you say a little boy is going to die?” I immediately looked for my husband in a moment of parental desperation; he was nowhere to be found, likely wrist deep in someone’s neck.

I always encourage the parents of my patients to be honest, even with challenging news, in a developmentally appropriate way. This is much harder as a mommy than as a doctor. My mind raced as I struggled to find the words. How could I explain that yes, it was sad, but that my work was also very rewarding, and what a privilege to walk in these sacred spaces with families from diagnosis to cure to sometimes death. A pang of guilt sprang up as I struggled to find the right words for my healthy child: What would I say if it was my own daughter who was struck with a fatal disease? I drew a deep breath in and drew her even closer in my lap.

“He’s much older,” I said, stretching the truth about my 20-year-old patient.

“What’s his name, what’s wrong with him?” she asked, drawing out the curious interrogation.

“Cancer,” I said. It was the first time I had ever uttered this word to her.

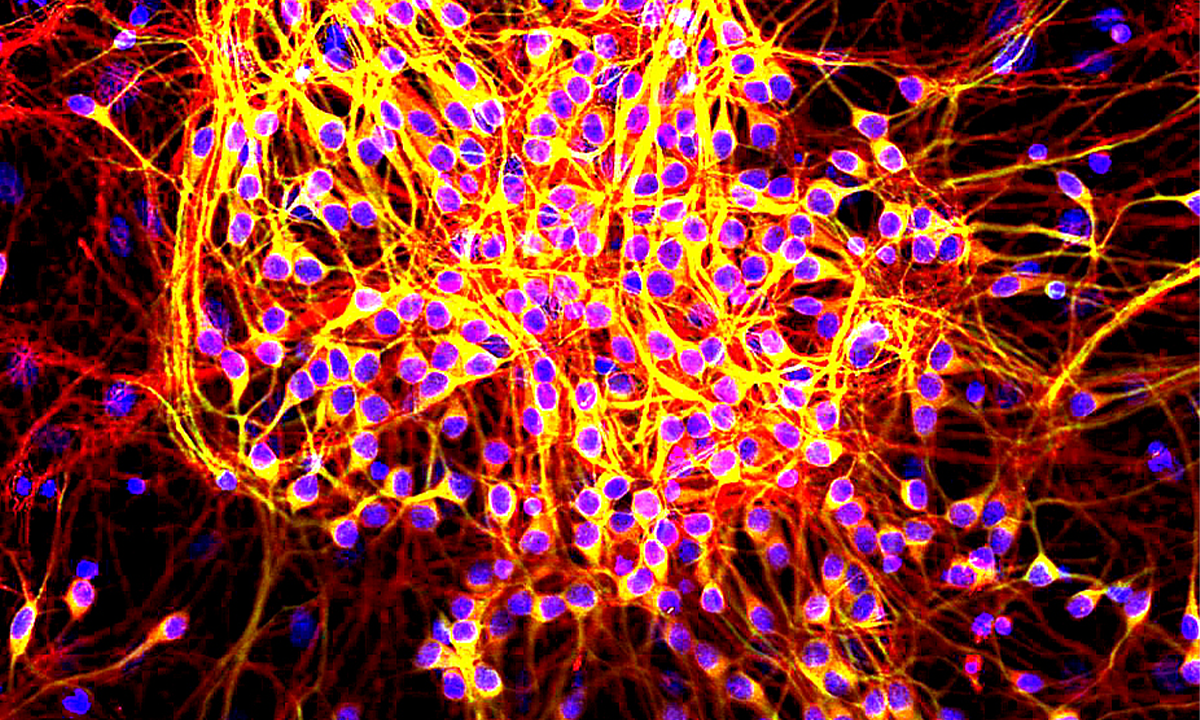

“What’s that?” she asked.

“Cells in your body that grow out of control,” was the best I could come up with.

“But Mom, how do you die from that?” she asked.

My inner monologue spat back, “Let me count the ways.” Before I could get something else out, she pressed on with, “Can you tell me his name?”

“No, sweetie, it’s private,” I said softly.

“You can’t even tell Daddy?”

“Not even Daddy.”

“But what if it is both of your patient’s?”

That occasion had arisen a few times in fact. “Well, in that case, yes.”

“I don’t want him to die, but if he does, then can you tell me his name?” There was a long pause. Before I could find an answer, she said softly, “So I can pray for him?”

My eyes welled up as I thought about my fellow mama across town, grappling with the impending loss of her son.

Surprisingly, my daughter was satisfied with our exchange. She reached her arms up and put them around my neck. I breathed in the faint lavender scent of her soft hair as I tried to cement every last detail of her in my mind. I took a moment to soak up the normalcy in my life, knowing all the things that can and do go wrong, wondering when disaster will strike in my own home.

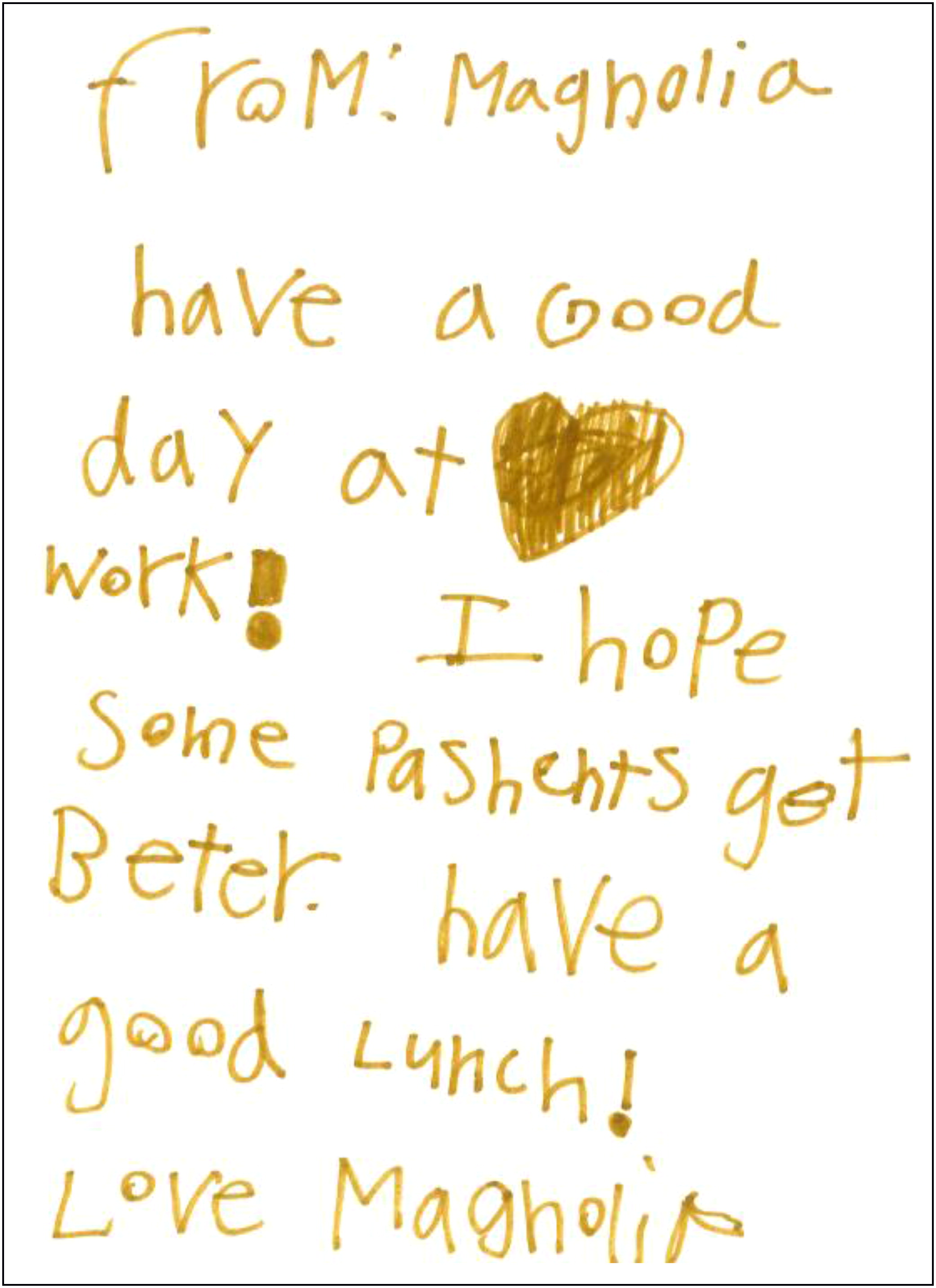

A few weeks later, I sat at my desk reflecting on my chaotic bulletin board that hangs right above it. It is haphazardly littered with the drawings; cards; and an endless stream of creative endeavors that get tucked into my work bag by my healthy, vibrant children. Their awkward smiles in school portraits with cheesy backgrounds stick out from the funeral mass cards I meticulously curate from all my patients who have died. My eye caught on a note that came folded up in my lunch earlier that day. I sat back and realized that on some level, that big talk about some big questions had made a significant impact on my six-year-old:

Reprinted from the Journal of Clinical Oncology