The disquieting sci-fi show Black Mirror has been on a bit of a hiatus since 2019—but no longer. The latest season, Black Mirror’s sixth, releases today. If you’re a fan of dystopian depictions of societal decay and social derangement brought on by technology that’s eerily close to being real (or real already) you can rejoice! I’ll be watching the newest episodes with you—and I wouldn’t be surprised if the computer scientist Iyad Rahwan joins us.

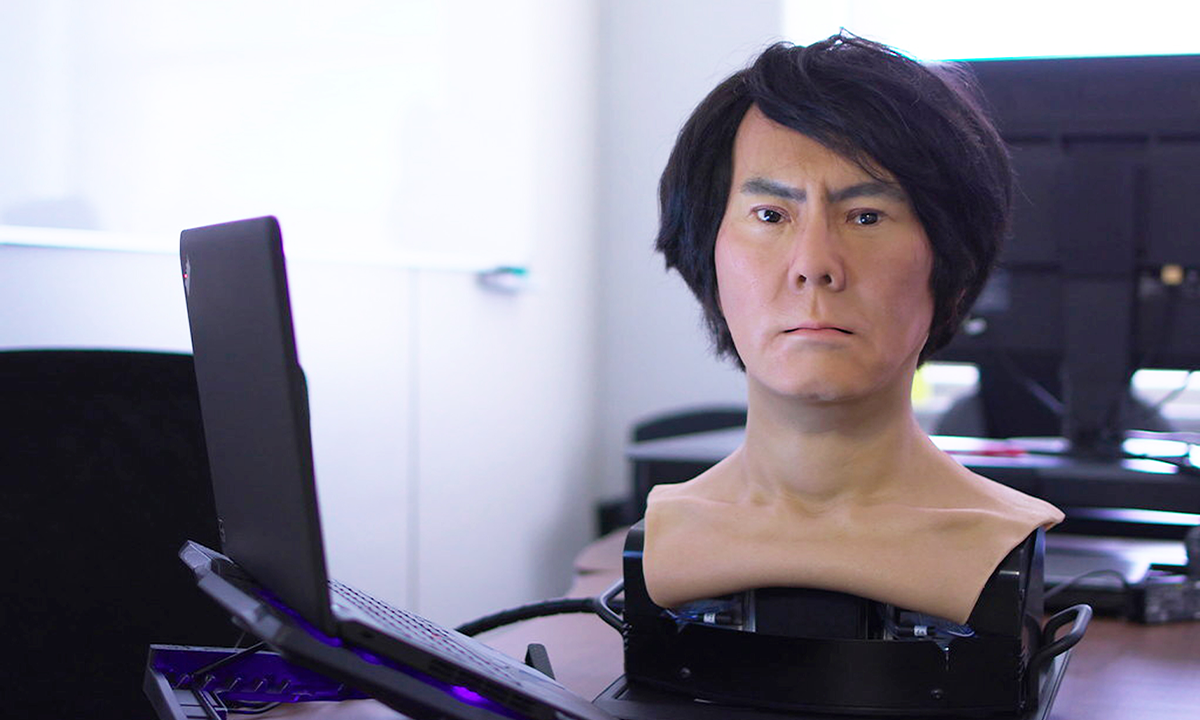

Rahwan directs the Center for Humans and Machines at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, where, according to his website, he’s focused on understanding “how intelligent machines impact humanity.” Given that avenue of curiosity, it seems inevitable that Rahwan would be inspired by the imaginatively bleak scenarios Black Mirror brings to life. And that’s exactly how his new paper, co-authored with social psychologist Nils Köbis and others, came about. The research explores a more benign version of the situation the Black Mirror episode “Men Against Fire” dramatizes. As Rahwan and his colleagues describe the episode, “soldiers perceive the world through a real-time AI filter that turns their adversaries into monstrous mutants to overcome their reluctance to kill.”

The researchers take the episode to be a meditation on the impact face-blurring technology could have on us ethically and psychologically. Many of us, they point out, are already desensitized to the routine use of sophisticated image-altering filters on apps like TikTok, where users can, for example, look like their teenage selves or, more controversially, touch up their appearance. “What we do not fully realize yet is that filters could also change the way others see us. In the future, metaverse interactions and offline interactions mediated by augmented reality devices will offer endless possibilities for people to alter the way they see their environment or the way they see other people,” they write. “In this work, we focused on a simple alteration, which is already easily implementable in real-time: blurring the faces of others.”

In three experiments, Rahwan and his colleagues had about 200 people play 10 rounds of two games online (specifically the Dictator Game and the Charity Game). In each game, you get to choose how much money ($2, in 10-cent increments) to give away to your partner who keeps the money you offer from one of the rounds as a payoff. In the Dictator Game, you keep what you don’t give away; in the Charity Game, the World Food Program keeps what you don’t give away. In two experiments, the researchers randomly assigned participants to have a picture of themselves their partner could see either blurred or unblurred. And in the third experiment, the subjects played the game while in a video call with each other, again with their faces blurred or unblurred.

Rahwan and his colleagues say they came away with a robust effect: People who were playing with a blurred partner in the Dictator Game allocated money more selfishly. “This result aligns with the idea that blur filters enable moral disengagement by depersonalizing the individuals we interact with,” they write. It also supports earlier research on the ways AIs interacting with humans can affect moral decisions. In a 2021 study, Köbis and Rahwan found that AIs could act as “enablers of unethical behavior” that “may let people reap unethical benefits while feeling good about themselves, a potentially perilous interaction.”

The results from the Charity Game, however, were mixed. In the video experiment, people gave their blurry partners more money than the charity; and in the non-video version, subjects did the opposite, giving more to the charity. What’s going on? “The social interaction with the partner is more pronounced in the video format through the interactive and simultaneous character,” they write, “and could potentially explain the flipped effect.”

On Twitter, Rahwan hinted that this is just the beginning of a series of experiments. “This work is part of our ongoing efforts to explore the concept of ‘Science Fiction Science’ (or sci-fi-sci for short):” he said, “to simulate future worlds, then test hypotheses about human behavior in those futures.” Stay tuned. ![]()

Lead image: marco martins / Shutterstock