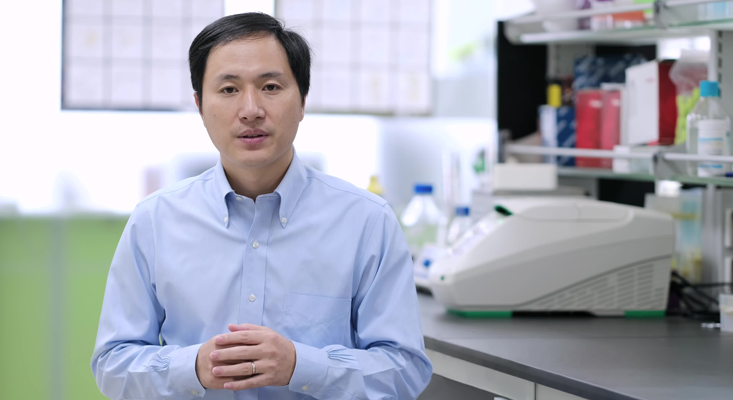

Last November Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced the birth of twin babies whose germline he claimed to have altered to reduce their susceptibility to contracting HIV. The news of embryo editing and gene-edited babies prompted immediate condemnation both within and beyond the scientific community. An ABC News headline asked: “Genetically edited babies—scientific advancement or playing God?”

The answer may be “both.” He’s application of gene-editing technology to human embryos flouted norms of scientific transparency and oversight, but even less controversial scientific developments sometimes provoke the reaction that humans are overstepping their appropriate sphere of influence. The arrival of the first IVF baby in 1978, for example, was denounced as playing God with human reproduction1; more than 8 million “IVF-babies” have been born since.2 As we face a global climate crisis, an article at Religion News Service questions whether proposed climate fixes based on geoengineering are playing God with the climate system.3 For many, the idea that mere humans can or should interfere in lofty natural or human domains, whether it’s the earth’s climate or human reproduction, is morally repugnant.

Where does this aversion to playing God come from? And might it present an obstacle to scientific and technological advance?

A paper published last month in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B is the first to systematically investigate aversion to playing God and link it to negative attitudes toward science and technology.4 Across seven experiments involving over 3,500 participants recruited within the United States, psychologists Adam Waytz, of Northwestern University, and Liane Young, of Boston College, found that judgments of “playing God” predict more restrictive views of technology use and more limited support for science.

In their first study, they found that the more a scientific procedure (such as genetic testing during pregnancy or cloning humans) is taken to involve “playing God,” the more likely it is to be judged morally unacceptable. A second study found a similar relationship for drone warfare, vaccination in childhood, the production of genetically modified organisms, and the use of technologies that contribute to climate change: The more an individual thought the issue involved playing God, the more morally unacceptable they judged it to be.

The researchers also found that individuals tend to vary in their level of “aversion to playing God,” and that this variability relates to more general attitudes toward science. Participants who endorsed one statement of aversion to playing God (for example, “it bothers me when people try to take on the role of God”) were not only more likely to endorse others (like, “there are some matters in the world that are beyond the sphere of human influence”), but were also more likely to support lower levels of funding for the National Science Foundation. Importantly, the pattern of correlations observed in this study (and all others) was not simply a reflection of participants’ political ideology, religiosity, or belief in God.

Most people don’t like to think of themselves as just another mammal among many.

Waytz and Young argue that, at least in some cases, aversion to playing God and negative attitudes toward science and technology are not only correlated, but related causally, where the former drives the latter. They also argue that aversion to playing God could hinder progress in areas such as reproductive technology, medicine, robotics, and artificial intelligence, where rapid technological advances are pushing the boundaries of what humans can achieve. This aversion could result in restrictions to research on gene editing in humans—which could prevent disease—or discourage the widespread adoption of artificially intelligent agents in decision-making roles that could improve the efficient and equitable distribution of resources. This makes it pressing to understand what underlies aversion to playing God. Is it something we can change? Is it something we should change?

It could be that aversion to playing God is simply a matter of people’s beliefs about the existence of God and God’s appropriate sphere of influence. But if not, what’s really behind it?

The data reported by Waytz and Young suggest that judgments about “playing God” and “belief in God” are not the same, at least in this American, and largely Christian, sample. While aversion to playing God was strongly and significantly correlated with belief in God in most of their studies, this association did not fully explain the link between aversion to playing God and negative judgments regarding technology and science. More telling, analyses of additional data from two nationally representative samples, with a total of over 2,800 participants, revealed that, of the 2 to 3 percent of respondents who indicated that they did not believe in God, 35 to 49 percent still expressed some or strong agreement with the claim that “human beings should respect nature because it was created by God.” Playing Devil’s advocate doesn’t have much to do with the devil these days; similarly, playing God—and a sense for what’s considered to fall within God’s sphere—might not have much to do with God.

Rather than reflecting a specific commitment to God, Waytz and Young suggest that aversion to playing God reflects “an aversion to human agency in a domain in which another agent is thought to be responsible.” For some people, that “agent” could be nature. In fact, one of their studies revealed a significant (though modest) relationship between aversion to playing God and belief in a “natural order.”

Yet this still leaves us with the puzzle of what drives aversion to scientific and technological intervention or change, whether it impinges on God’s authority or on some natural order: Why not celebrate human agency, and rejoice in greater control over the natural world? Answering this question takes us well beyond the data, but two hypotheses are worth a look.

First, it could be that aversion to playing God is a “moral heuristic,” as proposed by legal scholar and behavioral economist Cass Sunstein: a moral short-cut or rule of thumb that’s useful in many contexts, but that can also lead us astray. For instance, it could be that intervening in highly consequential but highly complex, nonlinear systems is especially risky, because we can’t generally be trusted to have a good handle on the likely consequences. This heuristic could be a good guiding principle in everyday life, even if it fails to apply to contemporary science.

If this moral heuristic is what underlies aversion to playing God, it could be important for people to appreciate the discontinuities between our everyday experience of bumbling about the world, and the much more sophisticated resources of our best-developed scientific practices and theories. It also makes it important to appreciate when our scientific understanding is—and especially when it isn’t—adequate to the task of evaluating the risks of, say, gene drives, a means of rapidly spreading new traits in a population. On this view, even if gene drives “could help solve some of humanity’s greatest ecological and public health problems,” as a paper published this month put it, some aversion to playing God might be warranted—but only if there’s a good correspondence between our intuitive aversion to playing God and what we really do and don’t know about the natural world.5 For most people, that kind of correspondence is unlikely to obtain.

When it came to romantic love, respondents were less likely to consider a scientific explanation.

A second hypothesis is that playing God could have the ironic consequence of placing us above the natural order in one sense, yet locating us firmly within it in another. To play God when it comes to human reproduction or human cloning, for example, we have to regard the very processes that make us human as susceptible to the same scientific approach that helps us build bridges and grow corn. And most people don’t like to think of themselves as just another mammal among many, let alone another multicellular organism, or another object. This reflects a belief in “human exceptionalism,” and it’s thought to help explain resistance6 to what Charles Darwin called our “lowly origin.”

Research also suggests that it might be unsettling to think of ourselves as falling fully within the scope of science. In a set of psychological studies with my former Ph.D. student Sara Gottlieb, we found that people were happy to embrace the idea that science could one day provide complete explanations for some aspects of the human mind, such as motor control or depth perception.7 But when it came to other psychological phenomena, such as altruistic behavior, romantic love, or belief in God, people were less likely to consider a complete scientific explanation possible, and more likely to find the very idea of such an explanation uncomfortable. One of the largest predictors of which phenomena were judged to fall within, versus beyond, the scope of science was whether the phenomenon was thought to be uniquely human: The more a phenomenon was thought to contribute to making us exceptional, the less possible and comfortable a scientific explanation was deemed.

If human exceptionalism explains our aversion to playing God when it comes to scientific interventions on humans, it might also explain our aversion to intervening in aspects of the natural world that make it special for us.

The trouble is that human exceptionalism is almost certainly false. If we are exceptional, it’s in no small part because of the progress we’ve made in understanding the natural world and developing tools to manipulate it. One of the most important outcomes of this understanding has been recognizing our own place within the natural world—one organism among many, albeit one we care a lot about.

Individual cases of playing God may well be morally reprehensible, just as any act or use of technology can be. Acts of playing God could be driven by morally unacceptable motivations, expose us to morally intolerable risks, or have morally objectionable consequences. Gene-edited babies are a case in point: Proceeding without adequately considering risks and consequences is morally unacceptable. But the mere act of playing God—of trying to improve ourselves and our world—is surely among the most human.

Tania Lombrozo is a professor at Princeton University in the Department of Psychology. Follow her on Twitter @TaniaLombrozo.

References

1. Nugent, C. What it was like to grow up as the world’s first “test-tube baby”. Time.com (2018).

2. Scutti, S. At least 8 million IVF babies born in 40 years. CNN.com (2018).

3. Chan, R. Controversial climate fix poses new question: Is geoengineering playing God? ReligionNews.com (2018).

4. Waytz, A. & Young, L. Aversion to playing God and moral condemnation of technology and science. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374 (2019).

5. Noble, C., et al. Daisy-chain gene drives for the alteration of local populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 8275-8282 (2019).

6. Miller, J.D., Scott, E.C., & Okamoto, S. Public acceptance of evolution. Science 313, 765-766 (2006).

7. Gottlieb, S. & Lombrozo, T. Can science explain the human mind? Intuitive judgments about the limits of science. Psychological Science 29, 121-130 (2017).

Lead image: ra2studio / Shutterstock