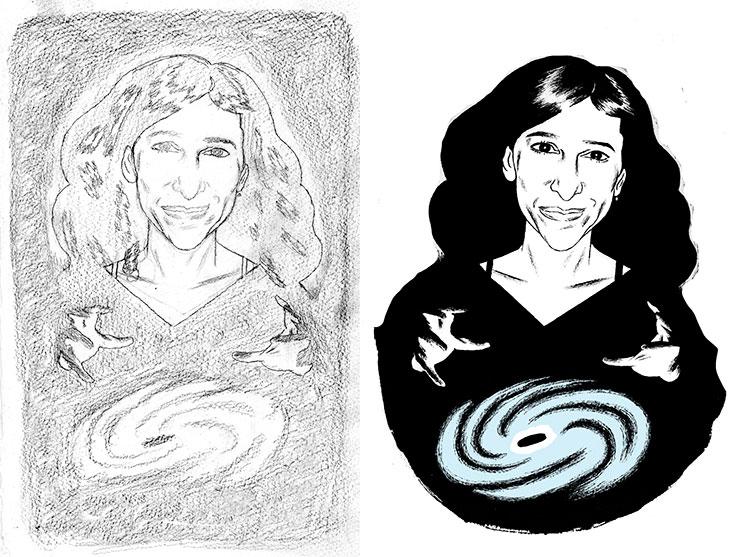

The “Caricature Generator” is a computer program that takes an image of a person’s face, finds its differences as compared to the “average” male face, and then exaggerates them in a novel rendering of the original portrait. Each face is broken up into 37 lines and 169 points—the differences come when the subject’s points don’t match the average. If the subject had a particularly snubbed nose, for example, then it would be caught by the program and then blown up by a factor of at least one. Cognitive psychologist Susan Brennan created it in 1982 while at MIT’s Media Lab, using it to analyze how well people recognized actual faces compared to caricatures, and found that the caricatures were more memorable, perhaps because they conferred individuality.

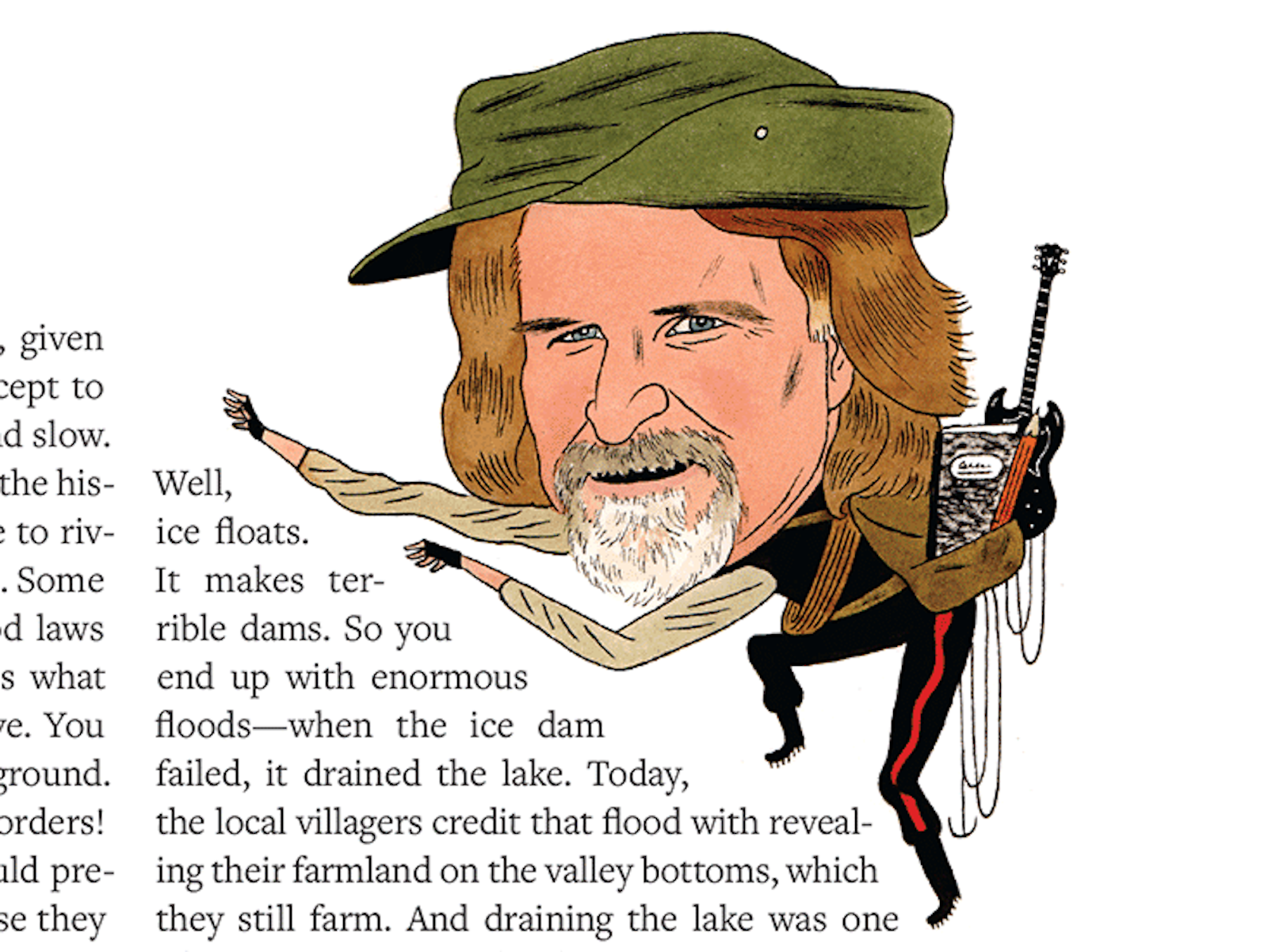

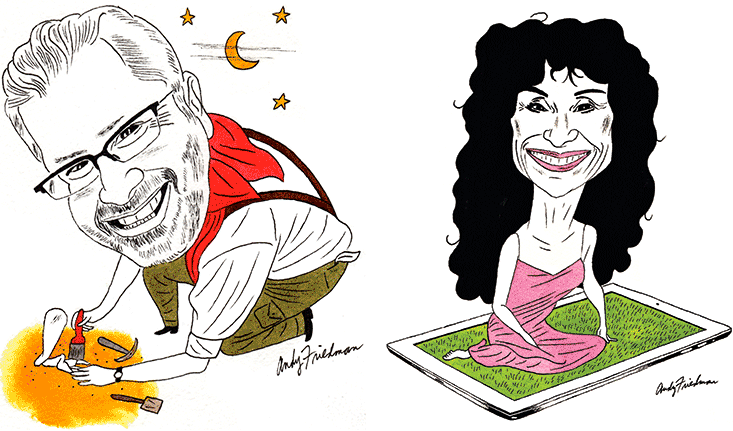

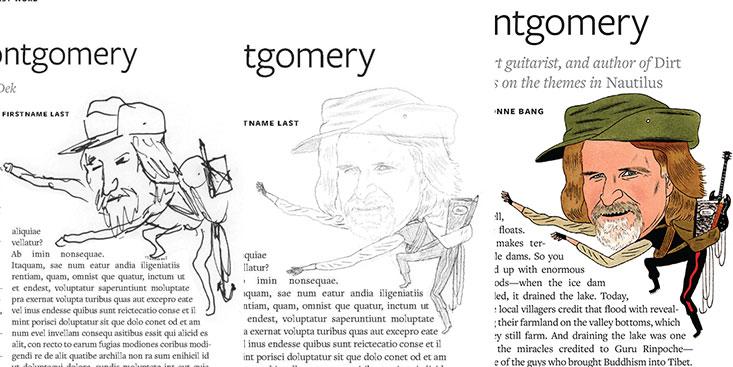

It is this injection of identity into a portrait that Nautilus’ own caricaturist, Andy Friedman, has sought to achieve with each of his illustrations accompanying our regular print column, “The Last Word.” Friedman works from photographs of each scientist to produce fun, stylized portraits that play with the scientist’s work and personality. To celebrate Friedman’s tenth caricature for us (the eleventh is shipping soon), we spoke to him about how he works.

Is caricature hard?

Alexander King, the obscure but legendary Art Director at LIFE during the middle of the 20th Century, proclaimed caricature as the most difficult artistic achievement. I’m not sure that I agree, but that’s what he said. I am a recovered Obsessive-Compulsive and a former “photorealist.” I once spent two years on a single oil painting. With caricatures, the aim is not to reproduce the physical appearance of a person in a literal way, but to interpret with swift strokes. The economy of visual language lends each portrait with an air of whimsy that a photorealistic portrayal might otherwise lack. This is why Alexander King held the ability to create a caricature with such high regard.

What features do you try to highlight in a caricature?

Whichever features stand out to me as the ones that make a particular individual unique. That varies from subject to subject, and day-to-day depending on my mood at the time of creation. The key, for me, is not to think about it too much and just let the pen do what it wants. That’s when the poetry happens.

How do you approach the subject?

I work from photographs or video stills. My process doesn’t change if I meet the subject, but the drawing might. Mostly I try not to think of the faces that I draw as having anything to do with a person, at all. I prefer to think of the face as a series of structural truths. My job is to break someone’s physical appearance down to line, color, and form. The minute I start worrying about what someone might think of my interpretation of their facial structure, it all falls apart. If I meet someone before I draw them, I could be more inclined to consider how they might react upon seeing their portrait. But, part of my job is to keep my ego, as well as theirs, out of the process.

Why is music important to your process?

I listen to a lot of country blues music. It reminds me of the power of simplicity. I probably listen to eight or nine hours of music a day. None of my process happens without making a playlist of albums that I will listen to while I do all of the work.

Of all the caricatures you have done for us, which was your favorite, and why?

The one that stands out in my memory is the drawing of the geologist and geomorphologist David Montgomery. Before then, I don’t believe that I ever incorporated a body of text as an element in a drawing. In this case, it became the mountain that Montgomery was climbing.

What do you think illustrators have to offer science and science journalism?

An illustration can encapsulate a complex idea in a few simple strokes. Science can be complicated. An illustration can make it easier for a reader to understand and absorb a topic. A picture also has the power to lead a reader to the page. So, I guess an illustrator can offer clarity of vision as well as a way to lead a horse to water. Think about how difficult it would be to describe a double helix without an illustration.

Do you think that art can change the aesthetic experience of science?

An illustration has the ability to clarify what text alone sometimes cannot. A double helix is a prime example, and so is a scientific formula. Conversely, sometimes an illustration has no value or meaning without the accompanying text. Scientifically speaking, text and images enjoy a symbiotic relationship.

Is there any dichotomy between art and science?

I don’t think there is much of a dichotomy between art and science. Both deal with making the intangible tangible, providing answers to difficult questions, and investigating new ways of seeing things. To me, art is the result of a passion. A painting, a scientific formula, a meal, a garden, a table, and thousands of other things could be considered art. The artist, scientist, chef, gardener, or woodworker is the person responsible for deciding whether or not what they create is art, not the viewer. In the eyes of nature, we’re all just doing our thing.

Who is your favorite science illustrator and why?

Probably Leonardo Da Vinci, who pretty much invented imagination. My favorite example would be his illustrations of mechanical wing devices. But his drawings of cats, skinned cadavers, and catapults also contain a significant amount of imagination at work. Before Da Vinci, imagination was not something that artists were free to explore. Art was created for religious purposes, or to commemorate the lives of the wealthy.

Claire Cameron is Nautilus’ social media & news editor.