On a brisk autumn afternoon in 1952, 16 wounded soldiers were brought aboard the Canadian destroyer Cayuga patrolling the Yellow Sea off the coast of Inchon, South Korea. Casualties of the Korean War, the men were in bad shape. Several would not survive without surgery. Luckily, the ship’s doctor had told the crew he was a trauma surgeon. Now, the portly, middle-aged man donned scrubs and ordered nurses to prepare the patients. Then he stepped into his cabin, opened a textbook on surgery and gave himself a crash course. Twenty minutes later, high school dropout Ferdinand Demara, aka Jefferson Baird Thorne, Martin Godgart, Dr. Robert Linton French, Anthony Ingolia, Ben W. Jones, and on this afternoon, Dr. Joseph Cyr, strode into the operating room.

“Scalpel!”

With a deep breath, the faux surgeon sliced into bare flesh. He kept one basic principle in mind. “The less cutting you do,” he told himself, “the less patching up you have to do afterward.” Finding a splintered rib, Demara removed it and extracted a bullet near the soldier’s heart. He was afraid the soldier would hemorrhage, so he slipped some Gelfoam, a coagulating agent, into the wound and it clotted almost immediately. Demara put the rib back in place, sewed the man up, and administered a huge dose of penicillin. Onlookers cheered.

Working all afternoon, Demara operated on all 16 wounded men. All 16 survived. Soon, word of Demara’s heroic feat was leaked to the press. The real Dr. Joseph Cyr, whom Demara had briefly known, read about “his” exploits in Korea, where he had never been. A military board grilled and quietly dismissed Demara to avoid embarrassment.

But the word got out. After Demara was profiled in Life magazine, the pretend surgeon got hundreds of fan letters. “My husband and I both feel you are a Godsent man,” one woman wrote him. A lumber camp in British Columbia offered him a job—as a doctor. Soon came a book about him and a movie, The Great Impostor, where the consummate actor was played by a relative amateur named Tony Curtis. Demara himself played the role of a doctor in a movie and considered going to med school. Too difficult, he decided. “I guess I’ve always wanted shortcuts,” he said. “And being an impostor is a tough habit to break.”

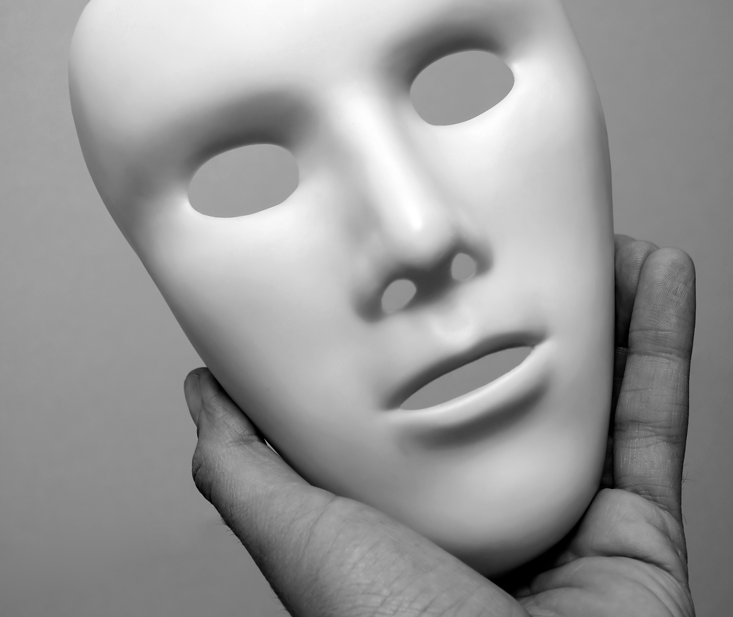

Con artists with a smile and a clipboard, impostors have a long history, a beguiling legacy of deceit that amazes and entices us. While most of us struggle to stay within social boundaries, impostors break through those barriers, striding effortlessly onto any stage they choose. Once in the limelight, they pull back the curtain of professional propriety, mocking its pretensions. Deep down, psychologists suggest, impostors appeal to us because we suspect that we are all, to some degree, faking it. Their stories expose the kaleidoscope of the self itself, and how to keep one step ahead of feeling like nobody ourselves.

Psychology professor Matthew Hornsey began studying impostors after being fooled by a colleague at the University of Queensland in Australia. Helena Demidenko, claiming Ukrainian heritage, wrote a prize-winning novel based on her childhood. But the truth soon emerged: Helena Demidenko was Helen Darville, an Australian woman with no ties to the Ukraine. Her entire history was a fabrication. Tricked and betrayed, Hornsey has since studied impostors and why people admire them. “We live in a world where often there are obstacles,” Hornsey has said. “And you see these people who take these crazy risks to catapult themselves into the social world that would otherwise be denied. That’s a romantic, attractive notion.”

Impostors also toy with our trust, the importance we give to a uniform, a title, a business card embossed with “Ph.D.” Envious of status, we gravitate toward those who take “shortcuts.” We don’t want our own doctor to be a fraud, but we thrill to the exploits of Frank Abagnale, portrayed in the Steven Spielberg film Catch Me If You Can, roaming the world as a consummate con artist, posing, faking, narrowly escaping, all before he turned 21.

But the psychology of fakery suggests a disturbing continuum. On one end stand the serial impostors like Demara and Abagnale. On the other end stand the everyday impostors—us. “Most of us engage in a low-key impostor-ism every day,” says Hornsey. “What if I smile when I’m not feeling happy? What if I pretend to be interested when I’m not? What if I pretend to be confident when I’m really feeling nervous? There’s a thin divide that separates impostor-ism from impression management or even social skill.” Impostors fascinate us, Hornsey adds, “not because we want to be like them, but because deep down we worry that we are like them.”

The common feeling of “faking it” starts with insecurity. Seated in a boardroom, a classroom, a high-level meeting, you are gripped by a nagging fear—you don’t belong here. Never mind your degree or your resume. You aren’t as smart as the others. You are an impostor. Such self-doubt is endemic enough to earn a label—the Impostor Phenomenon. When coining the term in 1978, psychologist Pauline Clance found it common among high-achieving women, yet gender blind studies have since shown that men are just as likely to feel like fakes, and that up to 70 percent of professionals experience the Impostor Phenomenon.

Psychologists blame the Impostor Phenomenon on bipolar styles of child rearing. Relentless criticism in childhood can internalize a parental scorn that no amount of success will silence. By contrast, the “perfect child” praised for the simplest drawing or project, can also grow up to wonder whether any of her success is earned. Regardless of the cause, the self-labeled “impostor” finds that each achievement, each compliment only deepens the fear that someday she will be revealed as a fraud.

Fear of faking it draws us to those who show no shame or concern while pulling off the most outrageous deceptions. “The public loves an impostor,” writes British journalist Sarah Burton in her book Imposters: Six Kinds of Liar. We thrill “overtly or secretly to this kind of taboo-breaking.” Told as children to tell the truth, Burton writes, “when we learn that someone has pulled off a monumental lie our first reaction is excited interest.”

A young man pretends to be the son of actor Sidney Poitier, conning his way into wealthy Manhattan homes. An Austrian woman convinces many that, despite speaking no Russian, she is the lost Princess Anastasia of the Romanov dynasty. A wily Frenchman passes again and again as a long-lost orphan. Perhaps we are beguiled by impostors, Burton suggests, because an imposter “simply goes further down a road that we are all of us already on.”

The faux surgeon sliced into bare flesh. “The less cutting you do,” he told himself, “the less patching up you have to do afterward.”

Psychologists ascribe several motives to serial fakery, each calling to our confused cohort of selves. Some impostors, Hornsey says, are the “rampant adventurers” we wish we could be. Others seek a sense of community denied them by shyness or alienation. Imperiled self-esteem is a third motive. Feeling like a failure, the skilled impostor easily gains prestige by pretending to be someone better, someone revered. Demara needed no psychologist to tell him why he posed as a doctor. “Anyway you looked at it, [Dr. Robert Linton] French was somebody good or bad,” Demara wrote. “Good or bad, Demara—that guy was a bum.”

Impostors, psychologist Helene Deutsch found, have often suffered stark reversals of fortune. Raised in successful homes, their entitlement is suddenly denied by divorce, bankruptcy, or betrayal. Feeling cheated, the impostor has no time to climb a ladder of success. Instead he restores status by grabbing it. Thus Frank Abagnale walked out of the courtroom where his divorcing parents were battling for custody and began living his fantasies. Tall, handsome, and looking 26 rather than his tender age of 16, Abagnale spent several years playing the role of airline pilot, security guard, doctor, lawyer … “A man’s alter ego,” he wrote in his memoir, “is nothing more than his favorite image of himself.”

We may all fake it on a small scale, but few of us have the intelligence or social savvy of the serial impostor. Without taking a single class, Abagnale studied law textbooks and passed the Louisiana bar. Demara could read a psychology text one day and teach psychology the next. Serial impostors are quick to defuse tension with a joke, and they are masters at reading a room. “In any organization there is always a lot of loose, unused power lying about which can be picked up without alienating anyone,” said Demara, who also posed as a prison guard, a professor, a monk, a deputy sheriff. “Make your own rules and interpretations. Nothing like it. Remember it—expand into the power vacuum!”

When it comes to ourselves, the impostor within has long been lurking. The word “person” is derived from the Etruscan phersu, meaning “mask.” Before being Latinized into “persona,” the term described masked characters in Greek dramas. Shakespeare ran with the idea, famously positing that “all the world’s a stage,” and we mere players whose parts shift with time and circumstance.

We know our lines; we know our parts. So why wear a mask? The impostor in us, psychologists say, feeds off an embattled self-image. Each morning we face down the mirror, disappointed by the person staring back. We’re only a shadow of what we thought we’d be. How to make it through another day? Put on a pose, become a “social chameleon.”

The term, says Mark Snyder, a professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota, describes those whose inner self differs from their public persona. “To some extent, we are all social chameleons,” says Snyder, who studies individuals and social interaction. “Just like the chameleon who takes on the colors of its physical surroundings, we take on the social colors of our social surroundings, molding and tailoring our behavior to fit our circumstances.”

Social chameleons, Snyder says, typically have a strong “self-monitor,” assessing each new situation, how to fit in, how to be liked. “High self-monitors” are found in many professions, including law, acting, and politics. But anybody who is a high self-monitor, says Snyder, would agree with the statement, “With different people I act like a very different person.”

Philosopher Daniel C. Dennett likens each of us to fictional characters. “We are all, at times, confabulators, telling and retelling ourselves the story of our own lives, with scant attention to the questions of truth,” he notes. Dennett sees the novelist within us as rooted in the brain’s anatomy, citing neurologist Michael Gazzaniga’s studies of the brain’s component parts, each with different perceptions. The components “have to act in opportunistic but amazingly resourceful ways to produce a modicum of behavioral unity,” Dennett writes. Hence “we are all virtuoso novelists who find ourselves engaged in all sorts of behavior … and we always put the best ‘faces’ on it we can. We try to make all of our material cohere into a single good story.”

Digital impostors slink and stride across the Web. You don’t really trust those gorgeous Facebook photos, do you?

Woody Allen took this idea to comical extremes in Zelig, his 1983 mockumentary about a human chameleon who changed his physical appearance from group to group. Leonard Zelig astonished doctors by morphing into a bespectacled psychiatrist, a dark-skinned jazz musician, a ruddy Native American, even a New York Yankees slugger in uniform. Under hypnosis, Zelig revealed why he presented himself as all selves: “It’s safe to be like the others.”

Why does it feel unsafe to be yourself? Perhaps because the self itself is a fiction. This is the conclusion of German philosopher Thomas Metzinger, director of the Neuroethics Section and the MIND Group at Johannes Gutenberg University. “No such thing as selves exist in the world,” Metzinger writes in Being No One: The Self-Model Theory of Subjectivity. “Nobody ever was or had a self.”

Our minds, Metzinger says, house only a deluded image of self, a “phenomenal self” that sees the world through a window but can’t see the window. Mistaking self-conception for an actual self, we struggle for coherence but must often settle for being one person on Tuesday, a slightly nuanced version of that person the next day, and who knows who come the weekend.

Metzinger says our shaky construction of self rests on a central principle. “There is the theory of terror management, which says that many cultural achievements are actually attempts to manage the terror that comes along with insight into your own mortality,” he says. “The insight that you will die creates an enormous conflict in our self-model. Sometimes I call it a chasm or a rift, a deep existential wound that is given to us by this insight—all my emotional deep structure tells me there is something that must never happen, and my self-model tells me it is going to happen.”

The self, in other words, is defined by our intimations of mortality. It distinguishes us from being nothing. So it’s no surprise we revel in personas. And now we have the perfect medium for it. MIT psychologist Sherry Turkle, author of The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit, calls social media an “identity technology.” “You can be this. You can have these friends. You can have these connections. You can have this love and appreciation, followers, people who want to be with you,” she has said. “People want this connection.” And often become online chameleons to achieve it.

Meanwhile for the pros, the stage lights are brighter than ever. On the Internet, noted the famous New Yorker cartoon of a hound at a computer, “no one knows you’re a dog.” Adopting a phony username, slapping “Ph.D.” on a self-published book, or just blogging with faux expertise, digital impostors slink and stride across the Web. You don’t really trust those gorgeous Facebook photos, do you?

Each of us is a cubist image, with no single self-portrait. Small wonder, then, we are drawn to those who seem so self-assured, so certain of who they are. These conniving artists present self-portraits that seem as masterful as a Rembrandt. Ferdinand Demara. Frank Abagnale. Leonard Zelig. And you? Who are you trying to kid?

Bruce Watson is the author of Light: A Radiant History from Creation to the Quantum Age.