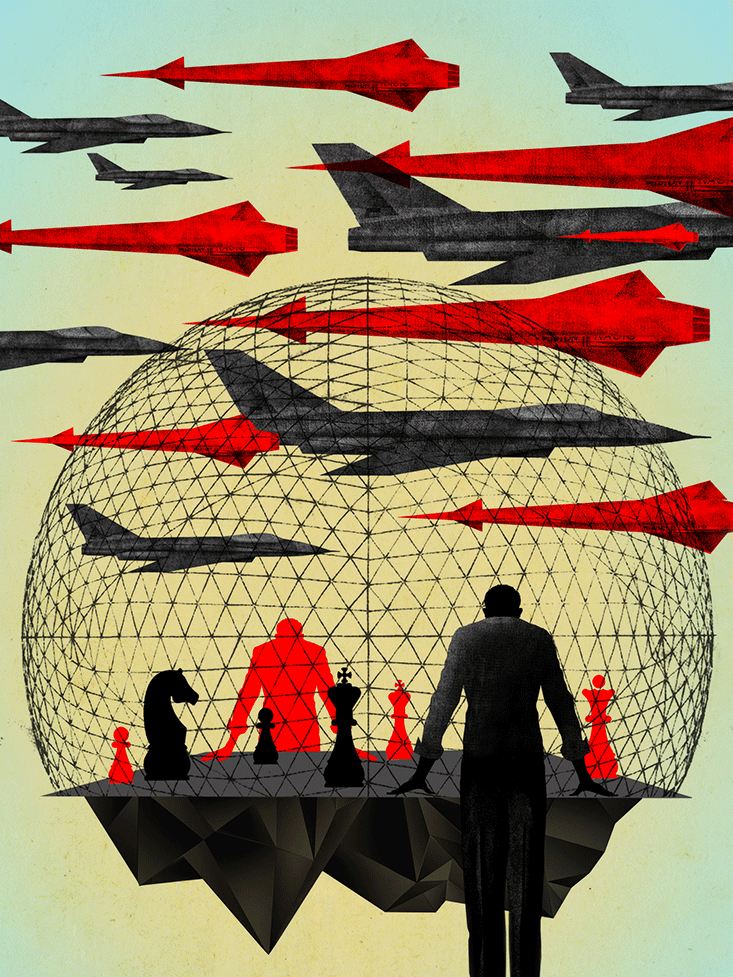

In the spring of 1964, as fighting escalated in Vietnam, several dozen Americans gathered to play a game. They were some of the most powerful men in Washington: the director of Central Intelligence, the Army chief of staff, the national security advisor, and the head of the Strategic Air Command. Senior officials from the State Department and the Navy were also on hand.

Players were divided into two teams, red and blue, representing the Cold War superpowers. The teams operated out of separate rooms in the Pentagon, role-playing confrontation in Southeast Asia, simulated in a neutral command center. Receiving each team’s orders, the command center’s experts modeled the blue and red moves, and issued mock intelligence reports in response. Reports reflected the evolving conflict, but the intelligence was intentionally distorted to replicate the fog of war. After days of playing out different scenarios, the war gamers reached the conclusion that civilians in the United States and the rest of the world would vocally protest an American bombing offensive.

The need to anticipate the dynamics of conflict increased as the U.S. Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in August of 1964, effectively declaring war on North Vietnam. So another war game was played.1 The objective was to play out the situation in Southeast Asia six months in the future. After ruling out an American nuclear attack, the teams role-played their way to a quagmire, in which the North Vietnamese countered every U.S. move in spite of lives lost and ruined infrastructure. The games forecast political crisis in the U.S., with no plausible path to American military victory. For the second time in a year, war games proved prescient, and also futile, as the government insisted on letting tragedy play out for real.

Buckminster Fuller foresaw the consequences of American intervention in Vietnam without the help of a military simulation. A professional visionary, Fuller was a self-made engineer-architect-inventor whose interests spanned from mathematics to philosophy. Born in Massachusetts in 1895, Fuller devoted his life to making “the world work for 100 percent of humanity, in the shortest possible time, through spontaneous cooperation, without ecological offense or the disadvantage of anyone.”

As the Vietnam conflict spiraled out of control, Fuller had a solution. His idea was simple: Instead of playing secret war games deep inside the Pentagon, the United States should host a world peace game out in the open. The concept was an elaboration on his proposal to build a geoscope inside the U.S. Pavilion of the 1964 World’s Fair. An animated Dymaxion world map would show all the resources on the planet, as well as all human and natural activity, from troop deployment to ocean currents.2 On this map, the world’s leaders and citizens of all nations would be invited to publicly wage peace. He cast the world game as a political system, a completely democratic alternative to voting in which people collectively played out potential solutions to shared problems.

“The objective of the game would be to explore for ways to make it possible for anybody and everybody in the human family to enjoy the total earth without any human interfering with any other human and without any human gaining advantage at the expense of another,” Fuller wrote. “To win the World Game everybody must be made physically successful. Everybody must win.”

Fuller’s world game was a means of achieving “desovereignization,” the importance of which he illustrated with a vivid military metaphor. “We have today, in fact, 150 supreme admirals and only one ship—Spaceship Earth,” he wrote. “We have the 150 admirals in their 150 staterooms each trying to run their respective stateroom as if it were a separate ship.” Those supreme admirals embodied geopolitics for Fuller. His world game was presented as an alternative to their warring.

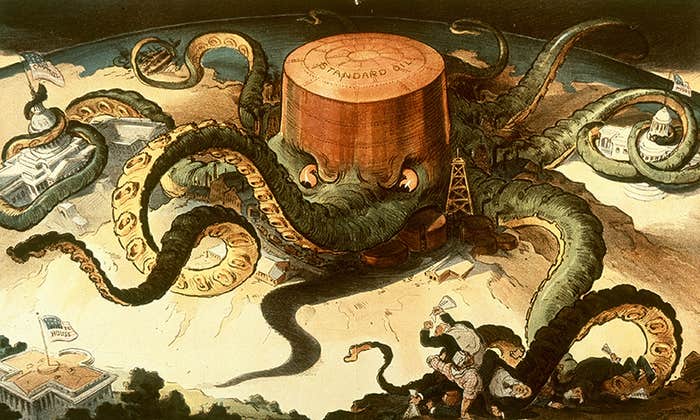

World games, Fuller insisted, were a remedy for war because they were the antithesis of war games, and an antidote to “zero-sum” game theory, a system in which conflicts were modeled mathematically to rationally determine the optimal strategy for winning. Fuller got his idea all the way to Capitol Hill. “Game theory,” he informed the Senate Subcommittee on Intergovernmental Relations in 1969, “is employed by all the powerful nations today in their computerized reconnoitering in scientific anticipation of hypothetical World Wars III, IV, and V.” The theory of war gaming, he said, “which holds that ultimately one side or the other must die, either by war or starvation, is invalid.” The U.S. government rejected Fuller’s plan. The Pentagon-funded RAND Corporation called his writings and Senate testimony “a potpourri of pitchmanship for an ill-conceived computer-based game” that would “retard real progress in the field.”

Yet for all the good reasons that Fuller and RAND had to be wary of each other, their differences were never as zero-sum as they professed. In the years since the Cold War, the relationship between games of war and peace has grown more nuanced, and intertwined in today’s computer game industry. As the maverick inventor envisioned, multi-user war games, networked across the globe, could allow the world to play for peace.

At the same time, the world has arguably grown more unstable. A nuclear-fueled standoff between two superpowers has been replaced by the unpredictable violence of myriad terrorist factions from the Taliban to ISIS. The impotence of the U.S. military as a counterforce—despite trillions of dollars in spending—shows the limits of conventional strategic and tactical thinking. In 2014 and 2015, the Atlantic Council, a think tank devoted to international affairs, conducted ISIS war games that concluded the terrorist organization is essentially impervious to U.S. forces. World peace is more elusive than ever.

Gaming new ways to reduce conflict has never been more urgent. Success will require all of the wisdom that can be drawn from war games over time. It will also take something that the 1964 war games so obviously lacked: the willpower to act on what gaming can teach.

War games are as ancient as gaming, and as primordial as war. Some of the most archaic games from China and Greece, such as weiqi and petteia, modeled the tactical movement of soldiers. And chess, the ultimate game of strategy, is a direct forerunner to the Pentagon’s Cold War simulations.

In its ancient Indian form, chess was called chaturanga. The game was played with markers signifying infantry, chariots, horses, and elephants, all overseen by pieces representing a vizier and monarch. Winning required the destruction of the opposing army or the capture of the king, much the same as in real battle at the time. While the game became less martial in outward appearance as it spread to Persia, China, and Europe, military men seem not to have been distracted by queens and bishops. The game provided mental training for commanders ranging from William the Conqueror to Tamerlane.

However, traditional chess, even when played with chariots and elephants, had obvious differences from battle. The opposing armies of chessmen were completely identical and the terrain was perfectly uniform, making the conflict artificially symmetrical. Both sides also had total knowledge of the entire battlefield, including all enemy positions. Orders were implausibly orderly, carried out instantaneously as each player politely took his turn. And there were no external factors akin to disease or storms. Chess was a closed system. Chaos and chance were eliminated.

This level of abstraction had obvious advantages. The purity of chess allowed players to focus on the grand challenge of anticipating an opponent’s behavior while upsetting the opponent’s expectations. But since strategic choices were never so stark in war, the most a commander could expect from chess was sharpened intellect, and there was always the threat that a young warrior would misunderstand what was being simulated and expect troops to obey as placidly as chess pieces.

Beginning in the 17th century, European military strategists considered ways in which to make chess conform more closely to real fighting so that chess could provide more well-rounded training. At first it was just a matter of enlarging the battlefield and making armies more varied with markers representing cavalry, artillery, and infantry. By the 18th century, the squares of the game board came to represent different kinds of terrain, either by varying their color or by transferring the grid onto a regional map. Rules were written to vary the speed at which troops advanced, based on whether they were on horse or foot, and whether they were crossing meadows or scaling mountains. Players were responsible for rudimentary logistics, ensuring there were supply lines to keep soldiers fed.

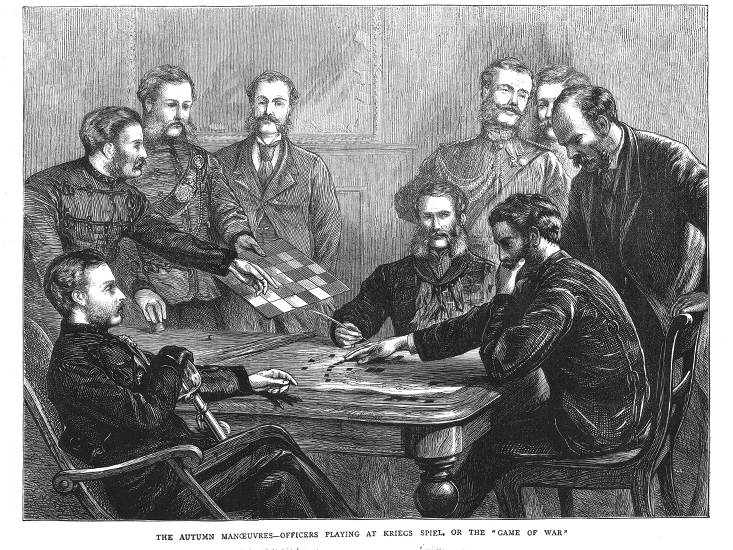

But that was just the beginning. The full transformation from chess to war games occurred in the 19th century, when a Prussian lieutenant named Georg von Reisswitz layered in aspects of a sandbox game invented by his father. The elder Reisswitz’s game was played with ranks of toy soldiers engaged in mock combat, where the outcomes of ambushes and battles were decided by dice. (The results of each dice throw were tallied according to real battlefield statistics, specifying the range of casualties to be expected in any given scenario.) The young lieutenant replaced his father’s sandbox battlefield with a flat topographic map, across which markers representing companies and units could be advanced at the rate permitted by the terrain. As in real warfare, neither side had total knowledge of the conflict. Each played on a separate board, with an umpire making his way back and forth. Rules derived from battlefield experience determined how much the umpire allowed each side to see of the opposition. Those rules also guided the dice-thrown results of combat. The game was known as kriegsspiel.

Germany used war games to invent the blitzkrieg, Japan to occupy Pacific island outposts, and the U.S. to distinguish the Marine Corps.

The verisimilitude of kriegsspiel impressed Karl von Muffling, the Prussian chief of staff, when Reisswitz demonstrated his game in 1824. Muffling placed an article in the Prussian military weekly asserting that kriegsspiel balanced the “frivolous demands of a game” with the “serious business of war,” and had game boards dispatched to every regiment. Thirteen years later, Muffling’s successor, Helmuth von Moltke, promoted kriegsspiel even more, making the game central to officer training by periodically bringing the whole War College out to the Prussian border in order to game hypothetical enemy invasions. The game would be played on a map corresponding to the surrounding landscape. Precise data for each maneuver would be collected by marching the local garrison through the formations on the game board. On this basis, Moltke not only provided training but also supplied tactical plans for the garrison in case of actual invasion.

Yet as the realism of kriegsspiel increased, the rules governing it—and the effort of playing it—threatened to overwhelm war gaming. Partly this was a practical issue: The more time required to set up and play out a scenario, the smaller the number of scenarios that could be explored. But there was also the deeper risk that greater verisimilitude would paradoxically make gameplay less relevant. It was the opposite of the issue with chess, where the lessons learned were universal yet abstract. In kriegsspiel, the lessons were often so concrete as to be sui generis. And even if the perfect occasion arose for applying a war-gamed tactic, the complexity of kriegsspiel made it difficult to determine whether the results were biased by how the rules interacted.

In 1876, one of Moltke’s officers, Colonel Julius von Verdy du Vernois, proposed an alternative: Replace the rules with the judgment of experienced umpires. “Free war games,” as they were known, could be played in two adjoining rooms with nothing more than a pair of topographical maps and two sets of markers. The umpire passed back and forth between teams, collecting orders and providing intelligence. Instead of using charts, players used their instinct to estimate how fast troops could advance, and the outcomes of battles were decided—without dice or casualty tables—at the umpire’s own discretion. This arrangement made the games fast like actual warfare, and the umpire knew the reason for his decisions, which meant he could help players to understand the outcome at any level of abstraction. The game was a prelude to discussion. Though Reisswitz-style games continued to be played, Verdy’s influence was profound. His free kriegsspiel established a continuum from rigidity to openness, just as Reisswitz’s rigid kriegsspiel established a continuum from abstraction to realism.

Games could be configured at any point along these two axes, optimized according to what the commander wished to achieve. And as war-gaming developed, expectations increased. Games could be used for training officers, building camaraderie, identifying leaders, understanding enemies, anticipating conflicts, inventing tactics, testing strategies, predicting outcomes. In the United States, where kriegsspiel was imported in 1887, one of the first questions was logistical. The Naval War College gamed different scenarios to determine whether fuel supplies for battleships should be shifted from coal to oil. The games indicated that a switchover would be advantageous. The Navy did it, fortuitously modernizing their fleet in time for World War I.

In Europe, kriegsspiel was widely used to develop strategies for ground war. Given Prussian tradition—and German delusions of grandeur—Germany was especially active, developing whole file cabinets of battle plans. One of the most promising played out the invasions of Holland and Belgium in order to quash the French army before the British could assist. The game determined that Germany would triumph against France as long as ammunition could be rapidly replenished. For this purpose, Germany built the world’s first motorized supply battalions, deployed in 1914. And the plan might have worked brilliantly, if the only players had been the German and French armies. But the German kriegsspiel failed to factor in the pride of Belgian civilians, who proved ready and able saboteurs—even of their own railroads—upsetting German momentum. Even more catastrophic, the game left out diplomacy which, by way of alliances, brought America into the war—and not on the side of the Reich.

The defeat of Germany in World War I suggested the need for another dimension in war games: a sociopolitical axis. Depending on the circumstances, war games needed to model the non-military implications of military actions, and to do so from the local to the global scale. Only when all three axes were properly accounted for could a game function meaningfully. And the appropriate level of abstraction, openness, and inclusiveness were different for every situation and every purpose.

All the major militaries gamed at multiple levels in the interwar period, with varied results. Germany successfully used war games to invent the blitzkrieg, Japan gamed the maneuvers their navy would later use to occupy Pacific island outposts, and the U.S. gamed the amphibious tactics that distinguished the Marine Corps. But games delving into politics were more treacherous. Free games played by Germany in the early ’30s—in which participants included diplomats, industrialists, and journalists—failed even to protect the Weimar Republic from internal collapse. In Japan, the Total War Research Institute held political-military games in 1941 that simulated the political interests and military power of countries including the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and America. The games correctly predicted a Japanese defeat of England in the Far East, incorrectly anticipated a German victory over the U.S.S.R., and utterly discounted the resolve of the United States. Certainly there was no premonition of how political conditions in Nazi Germany would give America the scientific brainpower behind the Manhattan Project, ultimately leading to the atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The predictive aims of the 1941 games ended in colossal failure. However, the real problem had less to do with game mechanics or faulty data than the belief that any global interplay of cause and effect could be decisively modeled.

Arguably the United States used war games most effectively in World War II because the U.S. military was most attentive to their limitations. A post-war assessment by Admiral Chester Nimitz provides some insight into the American approach. “The war with Japan had been [enacted] in the game room here by so many people in so many different ways that nothing that happened during the war was a surprise—absolutely nothing except the Kamikaze,” he said. In other words, the U.S. wasn’t presuming to predict the future—to simulate geopolitics fraught with unknown unknowns—but rather was creating a vast database of short-term hypotheticals, an industrial-strength version of what Helmuth von Moltke once attempted in Prussia. American gaming explored the problem space of war in the ’40s, and the games produced heuristics, or rules of thumb. The only limitation was the American military imagination, which was simply too American to conceive of Japanese suicide missions.

This exploratory approach was carried forward into the Cold War, reinforced by the circumstances of nuclear armament. The fundamental problem faced by both the U.S. and Soviet militaries in the 1950s and ’60s was aptly summed up by the RAND physicist Herman Kahn.3 When his expertise was questioned by military officials, he’d retort, “How many thermonuclear wars have you fought recently?”

The nuclear era was entirely unprecedented, and one wrong decision could cause the end of civilization. There was an urgent need to explore absolutely every eventuality while acknowledging that many eventualities couldn’t possibly be foreseen. The Pentagon gamely simulated Joseph Stalin’s sudden death and a Soviet first strike on Inauguration Day, role-played by mid-level military and government officials. The purpose of this free gaming was to develop intuitions: Since a good model would need to account for everything in the world—given that nuclear war was inherently global—good models were all but unbuildable. Instead the Pentagon opted for many inadequate simulations and gave low credence to any of them. In the words of one Navy analyst, gaming was a “training device for aiding intuitional development.” RAND referred to it as “anticipatory experience.”

Yet inevitably American government and military leaders wanted to master the Cold War. They sought victory over communism. Advances in computing stoked that ambition, as did progress in game theory as a model for non-zero sum games.

Robert F. Kennedy saw games as an alternative to political debate in which all interests could role-play their way to civil rights.

Around 1954, RAND analysts began to consider how the book, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, by mathematician John von Neumann and economist Oskar Morgenstern, could be applied to warfare. (The book attempted to establish economics as an exact science by modeling economic scenarios as multi-player games.) RAND started by mathematically modeling campaigns from World War II, working out how opposing armies should have acted. If fighting tactics from the past could be optimized, then why not future planning for nuclear engagement?

In 1960, Harvard economist Thomas Schelling explored the possibility in a book called The Strategy of Conflict. His book took up von Neumann and Morgenstern’s non-zero-sum games, showing that in an age of mutually assured destruction, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. could both win, with no risk of loss, if only they exercised mutual restraint.4 This was an excellent solution, except there was no obvious way to apply it: neither a framework for trust nor the political will to see the adversary benefit. The level of abstraction at which game theory was viable made the most compelling conclusions practically irrelevant. In that sense, it was like chess.

At about the same time that Schelling published his book, the U.S. military acquired a computer devoted to war gaming. Installed at the Naval War College at a cost of $10 million, the Naval Electronic War Simulator had no game theory in it. Rather the machine was a sort of electromechanical umpire, managing data and calculating dice-throws for role-playing games. Later versions had a similar function, though one side or both might be played by the computer itself, allowing the gaming process to be greatly accelerated. Countless games could be played, countless options considered, countless outcomes recorded. If game theory was the non plus ultra of chess-like abstraction, these computerized simulations were the ultimate extreme of kriegsspiel: resolutely concrete and vulnerable to programming biases.

For strategic purposes, game theory was too vague and computer simulations were too specific. The most versatile and insightful technique remained the oldest still in use: the 19th-century free war games of Julius von Verdy du Vernois.5

If only they could provide more than heuristics. (Legitimate skepticism about their predictive value may partly explain why gaming had so little sway over American policy in Vietnam.) An early intimation of what free war games could become was suggested by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in 1963. After playing a politico-military game organized by Schelling, Kennedy inquired about gaming a resolution to racial inequality in the South: an alternative to political debate in which all interests could role-play their way to civil rights. The idea was abandoned following President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, but a permutation arose in 1970, when Lincoln Bloomfield, a political scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, traveled to Moscow. As a guest of the Soviet government, Bloomfield orchestrated a simulation where Soviet, American, and Israeli officials unofficially war-gamed a hypothetical Middle East conflict akin to the Six-Day War. Bloomfield intentionally scrambled their positions. The pro-Arab Soviets played Israel, and the anti-Soviet Israelis and Americans played the Soviet Union. In these topsy-turvy circumstances, the Soviet “Israelis” surprised everyone by developing a policy of moderation.

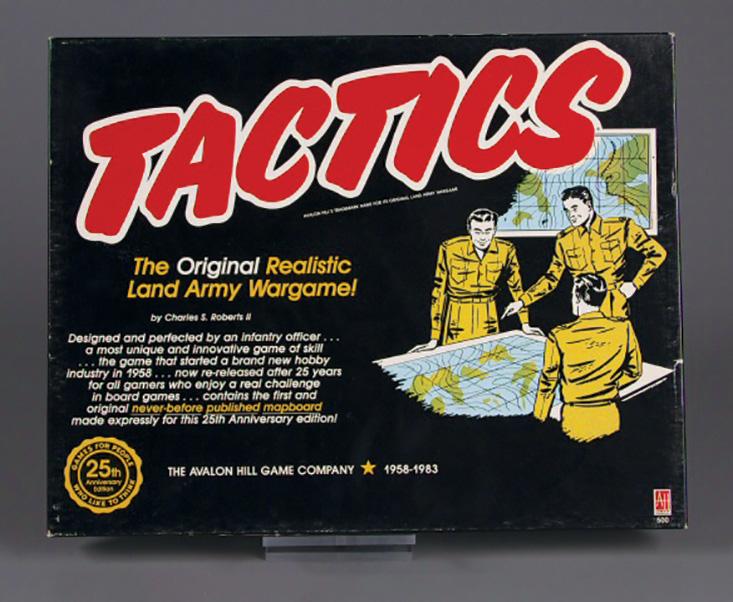

In 1953, a former soldier named Charles Roberts designed a simple war game for civilians. Tactics was played on the map of a fictitious landscape. Akin to Reisswitz’s kriegsspiel, there were tables to calculate casualties and counters to represent battalions. The self-published game sold well enough for Roberts to found a company, Avalon Hill, which launched the recreational war-gaming industry.6

Will Wright started playing Avalon Hill war games as a teenager in the 1970s. A decade later, as personal computers became commonplace, he decided to program a game of his own. Raid on Bungling Bay didn’t appear as cerebral as the Avalon board games he’d played. On the surface, it was a first-person shooter embedded in a flight simulator. But Wright had incorporated a sort of military-industrial realism, where the targets chosen by a player impacted enemy capabilities. The way to win was not to develop better reflexes, but to intuit the dynamics of weapons manufacturing and supply chains.

Wright’s next game dispensed with reflexes entirely. In SimCity, the player was mayor of a make-believe municipality, responsible for managing the urban dynamics of sustenance and growth. Crucially, there was no preordained goal. The player set personal standards of what the city should become and strove to make the sim conform to that vision. As in any real city, it wasn’t easy. (Attract companies by lowering taxes and the decline in social services may raise crime rates, driving away business.) The deep causal loops that made kriegsspiel so compelling were brought into the civilian realm, introduced to a single-player context where the conflict was internal. SimCity’s urban scaffolding could support endless variations: Like kriegsspiel, it was not a specific game but a logical framework for gaming. Wright has described it as a “possibility space,” in which a player becomes the game’s designer, and the design of a game is a design for society.

SimCity and Wright’s later creations—so-called “God games,” including SimEarth and Spore—provide a link between the tensions of war games and the intentions of Fuller’s world game. They were ludic platforms for utopian experimentation, and they foreshadowed one dimension of how Fuller’s vision could be brought into the present.

Another dimension was emerging around the same time that Wright was transitioning from Avalon Hill to Bungling Bay. At the University of Essex in 1978, two students, Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle, programmed a multiplayer adventure game for the campus computer network. The text-based role-playing game was the first of its kind, a sort of Dungeons & Dragons quest open to anybody who logged onto the mainframe. Trubshaw and Bartle called their creation Multi-User Dungeon, or MUD, a name that became the moniker for a whole genre of network-based adventure games, especially once the Internet networked everyone.

As advances in computing passed from the military to the commercial sector, the MUDs that followed Multi-User Dungeon evolved from text-based interaction to graphic exploration. These online environments invited discovery and conquest. Players could collaborate or compete. They could build together or kill each other. Eventually these modes of online engagement drifted apart. The collaborative impulse led to virtual worlds, including Second Life, populated by player-controlled avatars that keep house, socialize, and dabble in virtual sex. The competitive drive resulted in massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) such as EverQuest and World of Warcraft, in which avatars go to battle and collect loot.

The number of people who participate in virtual worlds and MMOs is staggering. At its peak, Second Life hosted 800,000 inhabitants—nearly the number of people living in San Francisco—and World of Warcraft reached a peak population of 12 million. Another massively popular genre—one more pertinent to promoting peace—is the God game genre. (Wright’s titles alone have sold 180 million copies.)7

Fuller wasn’t ambitious enough. The act of gaming must make peace in its own right.

But God games have never fit the massive multiplayer format, since the premise of a God game is omnipotence, which logically cannot be shared. Electronic Arts, the publisher of SimCity, tried to split the difference with an online multiplayer re-release in 2013. (Cities remained autonomous, but could trade and collaborate on “great works.”) The awkward combination of antithetical genres quite naturally provoked a backlash. SimCity cannot become what it was never meant to be. What’s needed instead are games designed from the start to allow a massive multiplicity of players to interact in open-ended possibility spaces.

Crucially, these virtual worlds would not be neutral backdrops in the vein of Second Life. Like SimCity and war games, they’d be logically rigorous and internally consistent. There’d be causality and consequences, and there’d be tension, drawn out by constraints such as limited resources and time pressure. Also like SimCity and war games, these virtual worlds would be simplified, model worlds with deliberate and explicit compromises tailored to the topics being gamed. There could be many permutations, so that none inadvertently becomes authoritative. The only real guideline for setting variables would be to adjust them to breed what Wright has described as “life at the edge of chaos.”

Within these worlds, scenarios could be played out by the massive multiplicity of globally networked gamers. Players wouldn’t need to be designated red or blue, but could simply be themselves, self-organizing into larger factions as happens in many MMOs. Scenarios could be crises and opportunities. Imagine a global financial meltdown that destroys the value of all government-issued currencies, provoking the United Nations to issue a “globo” as an emergency unit of exchange. Would the globo be adopted, or would private currencies quash it? And what would be the consequences as the economy got rebuilt? A single universal currency might be a stabilizing force, binding the economic interests of people and nations, or it could be destabilizing on account of its scale and complexity. It could promote peace or provoke war. Games allowing players to collaborate and compete their way out of crisis would serve as crowdsourced simulations, each different, none decisive, all informative.

As the number of players increased through the evolution of world gaming, the outcomes of these games would inform an increasingly large proportion of the planet. At a certain stage, if the numbers became great enough, gameplay would verge on reality—and even merge into reality—because players would collectively accumulate sufficient anticipatory experience to play their part in the real world more wisely. Whole aspects of game-generated infrastructure—such as in-game non-governmental organizations and businesses—could be readily exported since the essential relationships would have already been built. Games would also serve as richly informative polls, revealing public opinion to politicians.

Or they could play a more direct goal in governance. One of Fuller’s ideas—that gaming could serve as an alternative to voting—could potentially be realized with a plurality of people gaming national and global eventualities. For any given issue, different proposals could be gamed in parallel. As some games collapsed, gamers would be able to join more viable games until the most gameable proposal was played through by all. That game would be a surrogate ballot, the majority position within the game serving as a legislatively or diplomatically binding decision. Provided that citizens consented from the start, it would be fully compatible with democratic principles—and could break the gridlock undermining modern democracies.

When Fuller presented the world game as a method of reckoning how to achieve world peace, he wasn’t ambitious enough. The act of gaming must make peace in its own right. Operating at the scale of reality, the game that everybody wins must build our future world.

Jonathon Keats is a writer, artist, and experimental philosopher based in San Francisco and Northern Italy. He is the author of six books, including The Book of the Unknown, awarded the American Library Association’s Sophie Brody Medal in 2010. His art has been exhibited at institutions ranging from the Berkeley Art Museum to the Wellcome Collection. This essay is adapted from You Belong to the Universe: Buckminster Fuller and the Future, which will be published by Oxford University Press in April, 2016.