My grandfather wasn’t a big farmer, but his small garden in Kentucky was a miracle. There was rhubarb, corn, and peppers a-plenty, but mostly I remember the tomatoes. He bred his own, saving the seeds of the best specimens every year. By the time he was getting well into life, his tomatoes were outlandishly proportioned, irregular in shape, and incredibly delicious.

I thought about his garden when I saw the latest paintings by Mia Brownell, in her show Delightful, Delicious, Disgusting. It is currently on view at Juniata College Museum of Art in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania.

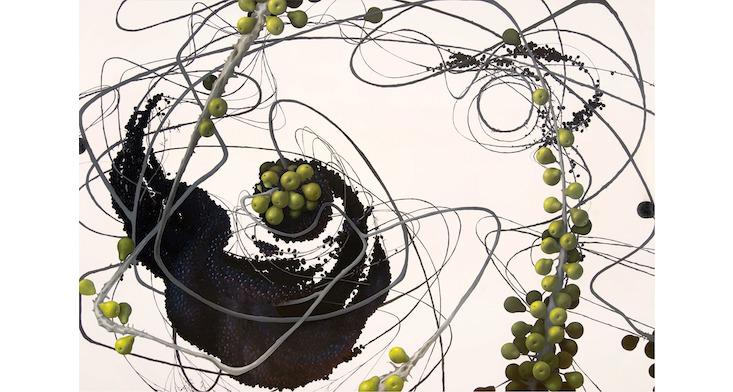

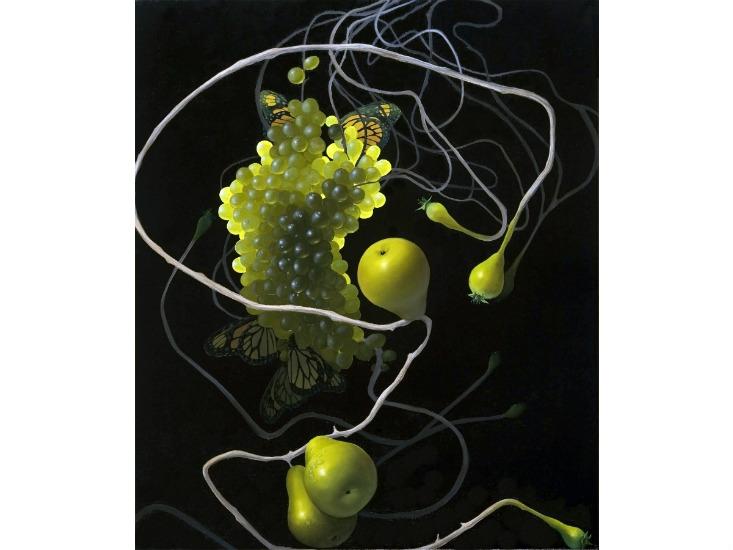

Brownell has been painting what she calls “molecular still lives” for over a decade. She begins most works with a base of abstract, swirling forms inspired by the structures of proteins, and then adds foods typically seen in traditional still lives. Grapes are a favorite of hers, as their orb-like shape lends a cellular look. Brownell strives to raise awareness and evoke primal questions about our food supply, from how it is grown and how it functions in our bodies, to how it impacts society.

“The paintings represent attempts to get entangled and occupy the ideas and images of food,” she says. The works also address emerging agricultural concerns. “Anything that can help raise awareness to what the industrialized food complex and big money is doing is good,” she says. To get there, Brownell often delves into the aesthetics of the digestive process, visualizing what happens inside our bodies when we ingest food from the outside world. If her paintings are not based on scientific data, they are based on realities of the modern food supply and how we are dependent upon and built from the foodstuffs we consume.

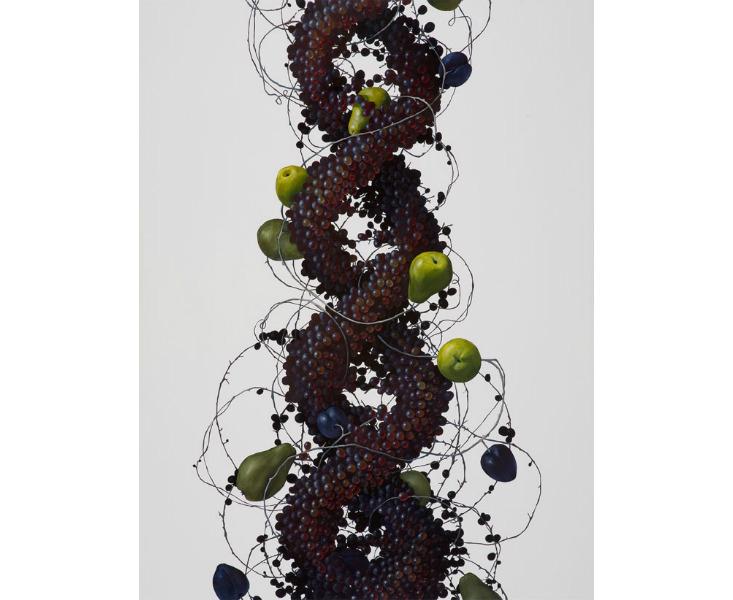

“In Still Life with Double Helix [below], the DNA and proteins symbolically embrace, in a merger of living organisms,” she said. “I don’t want to direct the viewer too much, but ultimately I would love for the art to speak to what it means to be human in the age of biotechnology and how we are merging with other organic life forms from the inside.”

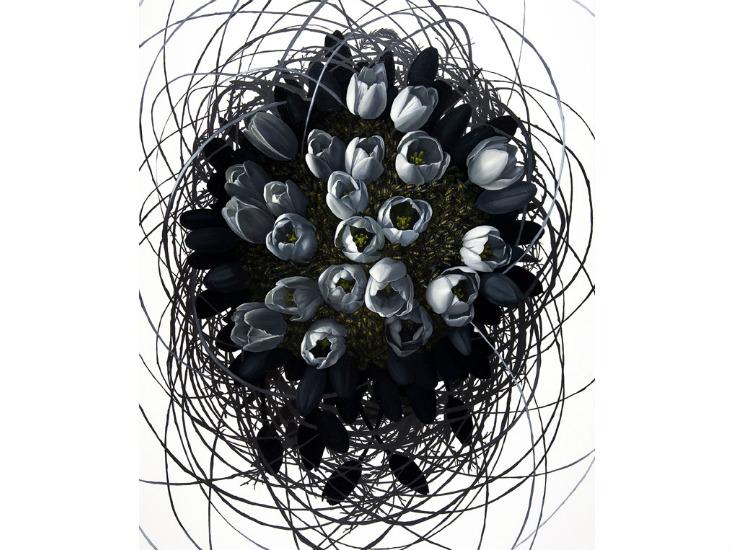

Other works examine the worrying disappearance of insect species. For instance Still Life with Lost Pollinators and Still Life with Lost Pollinators II show honey bees huddling together, no longer seeking pollen from nearby blooms. Both paintings directly address colony collapse disorder.

CCD causes honey bee workers to mysteriously abandon their hives. Current research points to disparate potential causes, including pesticides, nutritional problems, and pathogens. A solution has been hard to find.

According to the USDA, CCD killed off a third of the U.S. honey bee population last winter. (Typically around 20 percent of honey bee hives die each winter. CCD drives that number up to abnormal levels.) Every third bite of food we eat is dependent on the pollinating work of honey bees, and those crops generate $15 billion annually in the U.S. The honey the bees make brings in $150 million each year.

The beginnings of CCD may have been first reported by French beekeepers in the late 1990s. Perhaps this should be no surprise: French farmers remain closely tied to the land. They are legally required to use centuries-old farming practices that reliably produce their famously delicious foods. Certain pesticides and genetically modified organisms are banned. In the case of the bees, French researchers found that a pesticide called Gaucho was disorienting them, and they would stay outside their hives, where they would die from the cold; beekeepers called it “mad bee disease.” Gaucho was banned for use on sunflowers and corn.

One of the biggest recent trends in American agriculture is the boom in genetically modified crops, like Monsanto’s Roundup Ready corn, which is resistant to the company’s Roundup herbicide. By virtue of its very usefulness, Roundup Ready has been a disaster for American monarch butterflies. Farmers have used the pesticide and associated crops to more effectively eliminate weeds from their fields. Unfortunately, those unwanted plants include milkweed, the one plant that monarch butterfly larvae eat. This is part of the reason for a recent huge decrease in the insect’s population, and it’s attributable, indirectly, to the effectiveness and huge popularity of one genetically modified plant.

I wonder what my grandfather would think about the state of moden agriculture. It was over 20 years ago when we sat together on his porch swing. The light had faded out of the summer day and the buzz of insects rose in our ears. The swing moved comfortable and slow, like my grandpa’s voice.

“There just aren’t as many bees as their used to be,” he said, “and that can’t be a good sign.”

For me, now living in New York City, these memories seem to be from another planet, not from a town just 10 hours away. Like so many of us, I’m detached from the land I live on, except perhaps for the locavore meals my friends and I happily pay for. Meals with seasonal pea shoot salads with chervil vinaigrette, goat-milk feta and watermelon, all grown within 100 miles, is one way I still feel attached to nature.

For Brownell, food is nature. Especially these days, when nature is getting pushed further and further out, past the urban landscape, past the suburban sprawl, out past the highways, past the monoculture farms, and finally, to the country.

“Besides the trees next to the sidewalk and maybe watering plants,” she posits, “the food we eat is the most frequent encounter we have with nature.”

Heather Sparks explores art and science at Science Sparks Art. She studied molecular genetics at The Ohio State University, has a graduate degree in science journalism from New York University, and currently lives in Brooklyn.