At first, it was hard to attract women to China Lake. Maybe it was the slot machines at the officers’ club; or the taxi to the brothels at the nearby mining town of Red Mountain; or the bikini-clad “pinup” girl in every issue of the Rocketeer, with captions like “Eyes are upon shapely Philippine actress Sonja.” The nearby defunct mining town of Red Mountain advertised itself as a “living ghost town”—complete with women dressed like Old West barmaids and rooms above the bar where you could take them for a little living history. According to the base’s first commander, the men who came to work at China Lake were “war-weary veterans, with nervous disorders and physical problems,” just back from the battlefields of World War II. It was not a place that attracted missile wives.

The navy claimed the Indian Wells Valley in 1943. At the time, it was home to the Desert Kawaiisu and Panamint Shoshone, though Sherman Burroughs, who discovered the land, told the navy there was “no one there.” The valley was full of mining tunnels but not many miners, the Gold Rush having ended decades before. The few miners who remained had turned into what we call “desert rats.” One was living in three sedans—one for a kitchen, another a parlor, and the third for his bedroom—on the lake bed. Another was known locally as the “Mad Doctor” in the struggling town of Crumville, later renamed Ridgecrest. People thought he was mad because he gave up his job as an LA physician to strike it rich in the desert, though there was little gold to be had in the Indian Wells Valley. Crumville was a frontier town full of missionaries, saloons, brothels, homesteaders, and gunplay, with about 100 people.

In its early years, the base was half war town and half Wild West.

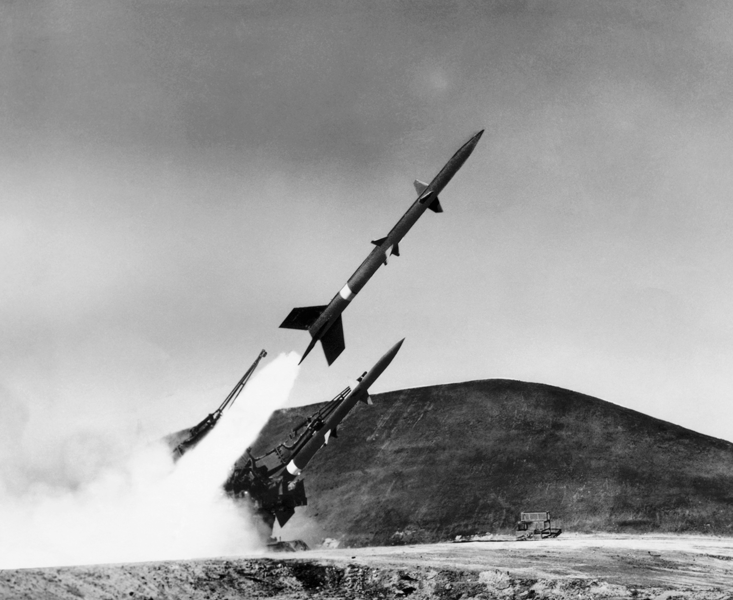

But base commander Sherman Burroughs had bigger plans. He wanted a permanent research facility to rival Hitler’s military base on the Baltic Sea, where engineers developed the V-1 and V-2 missiles that rained down on London in the Blitz. China Lake, Burroughs declared, should be “an American Peenemünde … a place where nobody knew what the hell was going on.” There would be, Burroughs said, “a huge laboratory wherein men and arms would be perfected for winning this war and for safe-guarding our national integrity in the future.” He wanted perfect men and perfect missiles. Today, a giant white “B” still hovers on a hill overlooking the town, commemorating Burroughs as our founder.

Burroughs’s only problem was women. Unlike sailors, who had no choice where they were sent, scientists would not permanently move to the desert without their wives. So China Lake was forced to clean up its image and look “safe” enough for women. First, the navy shut down the base casinos and the shuttle to Red Mountain. A short promotional film was made of the slot machines being run over by bulldozers, guaranteeing they would not miraculously reappear. Prospective employee families could watch this video, which lauded the “family friendly” environment of China Lake.

Next, they went after the brothels. In a 1952 memo sent to all base personnel, Captain Walter Vieweg, China Lake’s commander at the time, wrote, “All service personnel are prohibited from patronizing, entering, or frequenting the Owl Café and Hotel, Helen’s Place (also known as ‘Goat Ranch’), Mamie’s Place (also known as ‘Hog Ranch’), and J and J rooms.” All houses of prostitution. Unfortunately, the memo had the opposite of its intended effect since it provided directions to each of these secret establishments. It was even posted on their doors, serving as an inadvertent advertisement. The first thing I noticed about this memo when I found it in the National Archives was the name Captain Vieweg, the namesake of my elementary school after Groves. I weirdly thought of second grade, prostitutes, and farm animals all at once. It didn’t sit well in my stomach.

They built the brains that made the missiles run.

China Lake became a family-friendly environment by aggressively promoting activities such as church ice cream socials, Disney movie screenings, and the base’s endless “hobby clubs.” There was “Pebble Pups” (I joined), “Rock Hounds” (my sister joined), “Toast-masters ” (my mom joined), and “The Wildflower Club” (we all joined). There were also clubs for fencing, four-wheel driving, scuba diving, Ping-Pong, square dancing, watercolor painting, junior rifle, and many more. Christine and I chose the rock clubs because they met in the Quonset huts across the street from our duplex on Rowe Street. There, we learned to polish and grind desert rocks and slice geodes, making them perfect for our wall shelves.

But it turned out the best idea for keeping women in town was simply to hire them. The navy began to advertise a class called “Housewife to Draftsman in Only Twelve Weeks” in the local Rocketeer in 1951. Over time, this turned into a quota system for hiring women on the base. So when my mom suddenly said, “I need to get out of the house, Earl. I’m going crazy at home,” we all knew what that meant.

My mom wasn’t happy if she wasn’t working; she had always meant to return to work at some point.

“Hm …” My dad thought aloud for a moment. “Okay, you could give it a try. You might have a shot.”

“But I would hate to leave the kids alone after school,” she said. “Do you really think that’s okay?”

“We’ll be all right,” I quickly replied. “Christine can watch me.” She raised an eyebrow.

“We can get a babysitter, Mary,” my dad offered instead.

So, just like that, my mom disappeared. She had outstrategized us, getting a job in a section of the base called “Area E,” short for “Experimental Air Center,” where my sister and I were not allowed to go. Her division was Electronics Warfare. She told us only that rattlesnakes liked to sun themselves on the long airstrip there, which had been built for the B-29 bomber to carry the atom bomb. Overnight, we were a triangle that had imploded. The weapons were her new babies, not us, and one big family probably stood over and looked down at the weapons, smiling and holding hands.

I wanted her back waiting at home to see if we lived or died in the desert.

My mom was assigned to Code 35203 as a “math aid,” but all I knew was that she worked with the Gerber photoplotter, a machine that etches computer-drawn circuit board designs onto negatives. I only knew this because, when I called her at work, the secretary would often say, “She’s with the Gerber now.” Not me. The Gerber was in a darkroom where she could not be disturbed.

What I did not know was what she did in there. Only later did I find out that through a side door she would feed the Gerber negative paper. Then its innards would slowly digest it, spitting out drawings etched with a xenon lamp. It took around 10 hours. After the negative was done, it was passed to the photo lab for processing, then glued to a sheet of copper and placed in a chemical vat that would eat away everything but the etched design. The final product was installed in the missile’s nose, then taken to the desert for tests. My mom’s boss designed the circuit boards. My mom programmed the Gerber with Xs and Ys.

Together, they built the brains that made the missiles run.

The Gerber photoplotter, named after its designer, Joseph Gerber, who has nothing to do with baby food, was my mom’s new baby. My mom said the Gerber had to be kept in the dark and cleaned often. It also emitted a moaning howl that was loud enough to require headphones and could blind my mom with its xenon lamp unless she wore her dark safety goggles. It turned out that the Gerber’s sensitivities made people sensitive, too.

Her boss, Mr. Bukowski, designed missile circuitry and was a world-renowned expert on “spirals,” which I imagined was a Slinky so hard to design that it required a PhD. Their office, which was miles from anywhere, was a magnet for desert creatures seeking shade or water. Once, she said, a rattlesnake was found under a desk at work. Even so, it seemed to me, she was far more worried about the Gerber than that snake.

Her problems all started when she tried to change the filter in the Gerber. Technically, she was supposed to call the Gerber people for that, but she was a Depression-era kid and believed in fixing things herself. She tried to explain the problem with the Gerber people in a memo to Mr. Bukowski: “Their willingness to declare our lamps unusable may be motivated by their desire to sell a modification to the Gerber.” She thought a new filter would fix everything instead, that it would be a simple change.

But a co-worker of hers, Harris in Operations, disagreed. He was a middle-aged man with a loud voice and saggy face who thought those Equal Rights Amendment “Freedom Train” feminists were going too far. He supported Phyllis Schlafly, who said women should stay at home. So when he happened to catch my mom changing the filter, disobeying protocol, he knew he had found an easy target. He stormed in, towering over her, and shouted, “That’s an Operations job. Our filter changer handles that.”

My mom was taken aback by his bulk and apparent confusion. There was no “filter changer,” as far as she knew. She had assumed he would tell her to call Gerber. Nevertheless, she was driven back by his size and the way he leaned in over her. “Get out of here!” he yelled.

“Is there a filter changer?” she wrote to Mr. Bukowski from the safety of her office. He had not heard of one either. They decided to wait and see what would happen next.

He thought my mom was a false prophet. He thought this machine was good the way it was and did not need anything but him.

After a few days with work at a standstill and no filter changer in sight, my mom wrote to her division head—above even Mr. Bukowski—to explain that she was not allowed to change the filter and thus was unable to work. A simple filter change, she explained, would force the machine to recalibrate and fix the problem. Until then, any plots she printed would be bad. The spirals would not have their perfect arc. The missiles would not fly.

For Harris, that memo to Mr. Bukowski’s boss may as well have been an official declaration of war. When he got wind of it, he began his own memo-writing campaign. First, he sent one to my mom, even though her office was only down the hallway from his, stating that all further requests for plotting had to go through him. He accused my mom of secretly “tampering” with the Gerber and attached a “request form” for her to mail to him when she wanted to use the plotter again.

“More copies are available in my office,” he wrote.

The number of memos written, encoded, and passed between people who were working in the same hall might seem surprising to those who are not in Defense. There, everything has to be documented, double-entry-style, and preferably in acronyms. Otherwise, it does not exist.

Today, I picture my mom’s days unfolding at work like a twisted ballet, with the Gerber in the middle of the stage. Dancers come and go, sometimes blocking access to the machine, sometimes hiding behind it. Mom and Harris are locked in a ballet battle until one of them dies in the end, falling in a curtain of red ballet blood. Had the Gerber been a shrine and whoever approached it a prophet, the problem would have been that Harris did not believe in female prophets. He thought my mom was a false prophet. He thought this machine was good the way it was and did not need anything but him.

In contrast, for my mom the Gerber was a finicky child who had to be coaxed and preened so it would perform well. She knew that if the needs of the Gerber were ignored, it would create bad plots, little temper tantrums that would lead to bad missiles. Bad missiles made my dad leave town to fix them. And if a missile left a navy carrier chute with a bad circuit, there would be just one big plunk and then a long journey to the bottom of the ocean with all that money trailing behind. My mom believed the troops depended upon her and did not want a plunk. She did not want to waste that money. To her, sabotaging the Gerber meant sabotaging U.S. Defense. My mom must have thought she was facing an eternal enemy of the United States: treason. And all because Harris was withholding access to the plotter.

Finally, according to my mom’s notes, which told me the story of this drama, a new photoplotter operator appeared, Martha, who was petite with feathered red hair, diamond stud earrings, and bright red nails. She was a “downtime” person, which meant her “JO” (Job Order) had run out, leaving her without an assignment or funding from a particular missile program. In China Lake, to be on downtime was humiliating. It meant you were wasting “overhead,” or taxpayer money. You would be shunned as if you were contagious. Downtime people had nothing to do because they were not popular or smart enough to be picked for work on a particular missile. For instance, my dad put “AIM-9L” on his work stubs for years because he was being paid with money allotted for the Sidewinder. He was a Sidewinder person, whereas a downtime person is nothing. It meant you did not stay in one place for long but were more like a “temp” worker, sent to fill in holes everywhere, and the hole at my mom’s office was suddenly, mysteriously, for a “filter changer.”

So Martha was sent to Harris, who put her in charge of the Gerber. One had to wonder how she got to be in charge, to the point that in the end she could stop production on the Sidearm. Apparently, she had only a high school degree. Was Harris having an affair with her and treating the Gerber like a present for her? Was she just that pretty? Whatever the reason, my mom’s access to the Gerber did not improve after Martha arrived. Once, after getting two hours with the plotter, my mom had to beg Harris for two more.

Then he yelled at her, “Can’t you do anything right?” She started to cry. And the filter was never changed, not for four long months. If my mom believed in “working as good as any man,” Martha clearly had a different strategy. She believed in the power of rumors. First, Martha wrote a memo claiming my mom had been imagining problems with the Gerber and was compulsively tampering with it. Next, she started printing plots and showing them to everyone to prove the Gerber worked fine. In response, my mom printed her own plots, pointing out the problem to Martha. My mom wrote to Harris, “Only a non-trivial design, such as a modulated spiral, would likely repeat the problem.”

In response, Harris accused her of calling him “trivial.”

Who knows how long this “print off” might have lasted if Mr. Bukowski had not finally intervened. “The plots are bad,” he wrote to Harris. “I should not have to tell you this.”

I would not be surprised if Harris blew it up.

Next, Martha tried a different strategy. She claimed my mom’s software instructions were the problem, not the Gerber. She refused to communicate any further with my mom, who she said was being irrational. Because of this, Mr. Bukowski had to be constantly on the phone, even while on vacation, as a mediator between Martha and my mom. He even wrote to his boss to complain.

Finally, Martha hit on a winning rumor. “Why do you think Mr. Bukowski treats her better than everyone else?” she whispered, lifting an eye in insinuation. My mom overheard this and knew there was no evidence to prove Martha wrong this time. There was nothing to print, nothing mathematical to prove, which was her specialty. And rumors will always find allies. Soon my mom heard people whispering in the hallways that she was Mr. Bukowski’s “pet.” They questioned her credentials, wondering how she got the job without a degree in computer science, only medical technology.

One day, she heard something rattling in her desk drawer and opened it to find bullets. “They were about this size—” She held her fingers an inch apart when she told me.

“What did you do?” I asked, my eyes twice as big.

“I told some people about it, but they just shrugged. Then the janitor said he could use them, so I gave them to him. He said they were for a rifle.”

“What were they doing out there?” I said.

My mom shrugged. “I assumed they were for rattlesnakes,” she said. “But maybe they were for spies.” Then she laughed.

At the time, she was not laughing. Instead, she retreated to the couch and called in sick. That was when Mr. Bukowski finally stepped in. To me, Mr. Bukowski sounded like the kind of guy who could take a lot but had his breaking point. His parents had escaped from the Soviet Union, after all, so he must have known plenty about cat-and-mouse games, government bullies, and espionage. He decided he could play.

“I want you to keep an eye on the Gerber room and report to me who is using it every day,” he first wrote to the micro-miniature lab. They were in the room next to the Gerber lab.

“She is a perfectionist who holds the team together and could easily do any of our jobs. She needs a substantial raise.”

Soon the spy was writing on U.S. Navy letterhead every day, “No one today.” Next, Mr. Bukowski passed this information up to his boss: “No one today.” Evidence against Harris began to mount. Cases were being prepared. The plan was to prove that Harris was deliberately withholding the Gerber from my mother, claiming it was in use when it was not. They needed the double-entry ledger for that.

One day, Mr. Bukowski urgently needed plots for a trip to Dallas, but when my mom went to the Gerber room, she found it locked. The secretary then told her that both Martha and Harris had gone out of town for a few days and had taken the key. In a panic, my mom burst into Mr. Bukowski’s high-level meeting to explain. A sea of desert- grizzled engineering faces looked up at her.

“They’ve … they’ve gone,” my mom sputtered, humiliated. “They took the Gerber key!”

Mr. Bukowski had to cancel his trip to Dallas, the contractors had to postpone the missile production schedule, and ultimately the missiles may not have made it to the field in time. This was when Mr. Bukowski, a mild-mannered Polish man whose parents had told him to be grateful every day for what he had, finally lost it and was no longer grateful. He wrote to his boss, “The generating of high quality Gerber artwork has always been a challenge and undoubtedly will continue to be so; but the events of the last four weeks were almost enough to make me look for some other kind of work.”

And because Mr. Bukowski never lost it, a decision from above finally came down. A memo arrived from Code 35, above them all, copied to everyone involved. It read simply, “Any problems with the Gerber will be solved by Mary.” The verdict was in.

My mom lost many battles but finally won the war. But war leaves scars, and living next to the enemy, even after a détente, is never easy. After that, my mom suffered from a lack of confidence. Since my parents were from different branches and could talk only on a “need to know” basis, she could not tell my dad what was going on. He started to draw the blinds when she was on the couch, afraid she would die as his mother had done. He worried about having to travel so much with all of us left in his wake, bouncing and about to upturn like a boat. My sister would stare at him with her serious glasses face, perched and waiting for him to fall over, too.

The Gerber never fully recovered either. After being fussed and fought over so much, it decided it had had enough even after my mother got full custody. The fight had been too long, the adjustments too few. Its lamp exploded, destroying the mirror and the lens. After that, my mom explained, “It never got back into perfect adjustment.”

I would not be surprised if Harris blew it up.

If I asked my mom what she did at work, she would always say, “Oh, I was at the bottom of the totem pole—nothing important,” followed by, “People always said I was too slow.” Of course, partly this was my mom’s personality. Like my dad, she could be shy, humble, and stoical. She once said, “I’ve always been a nobody all my life. Your dad was always more popular at church.” I found this hard to believe, since my dad was the quietest person I have ever known. Nevertheless, after a lifetime of hearing my mother say such things, I truly came to believe them. At least, I assumed my father had the more important job at China Lake. Imagine my surprise when I discovered her work file, which held the Gerber memos.

They also held so much more.

My mom started as a GS-3 math aid, which involved using a miniature calculator and “keypunching data and programs” into the mainframe computer, a machine that took up the whole basement and had to be fed wallet-sized cards full of punch holes. But within a decade, she wrote of her credentials, “I have a system level knowledge of Tomahawk’s navigation,” including its “Inertial Navigation System (INS), Global Positioning System (GPS), barometric and radar altimeters, pre-stored terrain altitude profiles (TERCOM maps), and terrain imagery.” She could change a torpedo heading or launch point with the stroke of a DOS (disk operating system) programming line and, out of sheer boredom, once designed a laser bar-coding program years before anyone had heard of such a thing. She wanted to keep track of government property because she thought too much of it was disappearing. While my dad evaluated pitch and roll, my mom prepared the simulation programs and test plans for him to follow. She plotted his results. She analyzed his data. In one yearly review, her division boss wrote, “She is a perfectionist who holds the team together and could easily do any of our jobs. She needs a substantial raise.” Imagine that. She not only wrote computer programs, but also converted them to other languages as computers were evolving. She could even build a computer.

After some research, I discovered that my mom’s job was not that unusual for women at the time. Called “computresses,” women were once hired to operate 40-pound calculators that did nothing more than add, subtract, and divide. They did the math for the engineers. Back then, this was considered “clerical,” or women’s work, like typing. But slowly, computers evolved from these motor-driven calculators, and women were the only ones who knew how to use them.

By the time my mom arrived on the scene, calculators were already “miniature,” but computers were enormous. She was at the forefront of the shift to computers that was a room-sized IBM mainframe set up in the basement. She told stories about “punch cards” and how the IBM had to constantly be fed with them. That was “programming” then. Ironically, as computers became central to the process of building a missile, and then guiding missiles, women became central, too. The men did not know how to use them. My mom once said to me, “I was shocked that these guys did not know how to do basic things like plotting. I had to do everything for them. Except for Mr. Bukowski, of course. He knew it was important to learn.” Nevertheless, the men still got the big salaries.

Imagine that.

Karen Piper is the award-winning author of The Price of Thirst, Left in the Dust, and Cartographic Fictions. She’s won the Sierra Nature Writing Award, the Next Generation Indie Book Award, and fellowships from the Huntington, Carnegie Mellon, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. She is a professor of literature and geography at the University of Missouri.

From A Girl’s Guide to Missiles by Karen Piper, published on Aug. 18, 2018 by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2018 by Karen Piper.