How is he doing?” the clinic nurses would ask me worriedly. “He is a superstar, he will make it,” I would confidently respond. He had convinced me that he would pull through; that he was stronger, tougher, and smarter than his disease—a real life superhero—and, against my better judgment, I believed him.

This was not without good reason. He was an award-winning lawyer who was revered for his ferocious work ethic and brilliance. He tirelessly fought for civil justice, defending equality and, at the same time, earning accolades for his humanitarian efforts. He was a competitive runner and triathlete, logging dozens of miles per week and recording Olympic qualifying times. A true Southern gentleman—he was kind, decent, and polite to a fault. He was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in his late 50s; despite an induction regimen of corticosteroids, dasatinib, and high-dose methotrexate, he did not lose a day of work or a strand of hair.

He was a hero because he would not let cancer interfere with who he was or what he stood for.

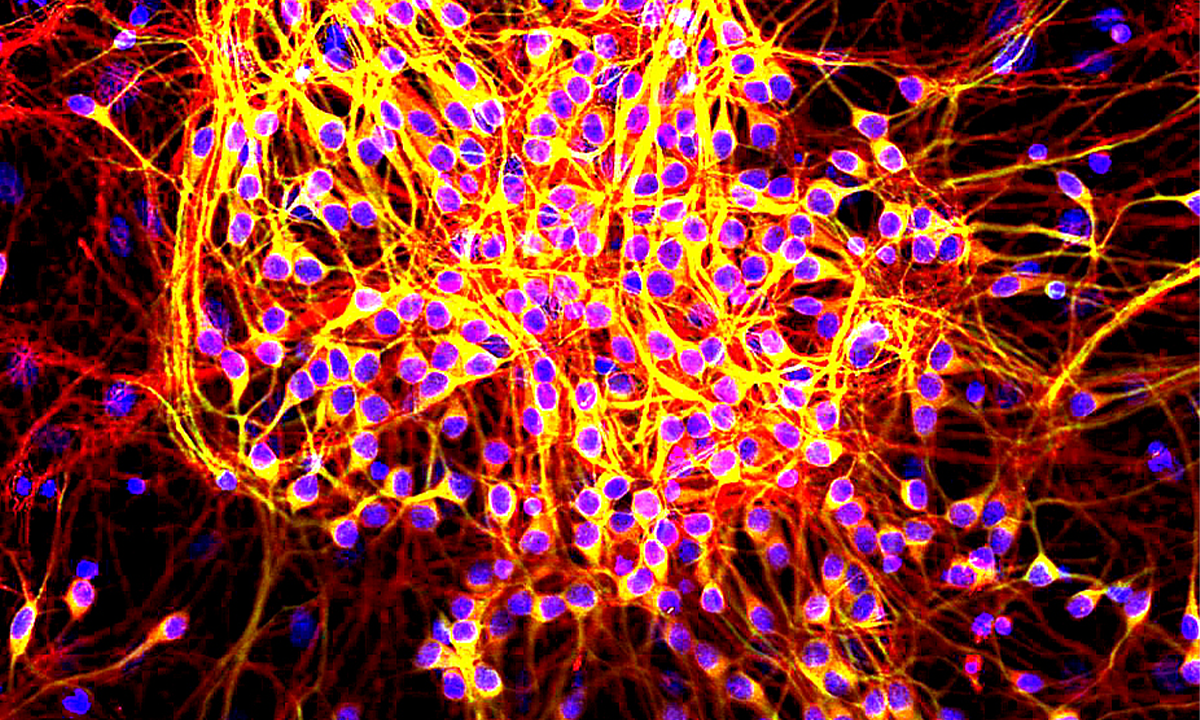

When we first met to discuss his upcoming bone marrow transplant, he assured me that he would be my star transplant patient. We reviewed his diagnosis: not an issue—he had recently read a textbook on acute lymphoblastic leukemia. I explained my concern regarding the persistence of a minimal residual disease population in his recent bone marrow examination; he was confident that the transplant would take care of this, and that he would achieve a complete remission in no time. We reviewed his caregiver plan, as he was single and did not have family in the area. He informed me that he was hiring full-time caregivers and would stay in a rented apartment across the street from the hospital for as long as necessary. I brought up graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Not to worry: He knew all about it and could recite the associated signs and symptoms. He won me over with his knowledge, strength, and utter conviction in himself.

I buried my anxiety and planned his transplant. He had an HLA-identical sibling, and I would use a chemotherapy preparative regimen rather than high-dose total body irradiation, which I hoped would result in fewer adverse effects. Everything was going to be fine. I was a competent physician and he was an incredible patient.

And everything did go unbelievably well—at first. He breezed through the transplant hospitalization, waking at dawn to conduct international meetings in business attire from the conference room of our transplant unit. Despite receiving an ablative preparative regimen, he had no mucositis and did not require a single transfusion. He had no evidence of GVHD, and within weeks of hospital discharge, he was out running several miles a day wearing his HEPA-filtered mask. I began to relax; he was handily winning the battle.

A twinge of anxiety resurfaced when his bone marrow biopsy—three months after undergoing transplantation—revealed a small population of residual leukemia cells. By that time, he had convinced me that he should return to full-time work. I voiced my concerns and told him that we would need to begin tapering his immunosuppression in addition to restarting dasatinib. He reluctantly agreed, but he was already focused on his next mission: preparing for and winning his upcoming court trial. I did not know how to reconcile my doubts with his steadfast belief in his ability to defeat this disease. Rather than harping on what could go wrong, I chose to bury my own voice and believe that, with his strength and my oversight, he could continue to both outsmart his opponents in the courtroom and destroy the leukemia cells in his marrow.

During the next two months, he seemed to be winning on both fronts, with a successful trial and a significant decline in disease burden, when a new enemy emerged. Between his business trips, I received an email that stated, “I think I have GVHD.” He had noticed a progressively worsening rash and mouth sores for a couple of weeks and was congested with a new cough. In the clinic, his skin raged with erythema, he had a mouth full of ulcers, and both sclerae were diffusely injected. “Why did you wait so long to let me know?” I nearly shouted at him. He had been in the thick of a case and had assumed that he would get better without intervention. I felt a sense of dread; I had seen enough aggressive presentations of new onset chronic GVHD in my young career to know what might lie ahead.

We were desperate to save him; I was desperate to save him.

A few days after the start of treatment with prednisone, he emailed me that his rash was resolving and his mouth felt much better. “Can you reduce my steroid dose, please?” he asked. “I am not able to concentrate on my work and the steroids are making me feel terrible.” Once again, I warily complied; the brilliant attorney seemed to be triumphing easily over yet another adversary.

However, within days of reducing his prednisone, the GVHD roared back. His skin began to peel and his hands were cracked and painful. Inflammation exploded in his lungs, which resulted in respiratory failure. Rather than succumbing to intubation, he fought ferociously. He continued on full face mask at 100 percent FiO2 in the intensive care unit for more than a month while conducting daily work on his laptop. He participated in high-level conference calls with the mask pulled down half over his mouth, engaged with physical therapy from his critical care bed, and told me of his life’s work defending companies he believed in, people he cared about, and those who would not otherwise have had a voice or a champion. When noninvasive oxygenation was no longer effective, he made the difficult decision to undergo extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, knowing that the likelihood of success was low and the risks of failure or fatal adverse effects high. He was only the second transplant patient at our institution to be considered for such a high-risk intervention. We were desperate to save him; I was desperate to save him.

Days became weeks under constant assault of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. His liver began to fail. His blood counts steadily worsened. Leukemia cells began to rise in his bloodstream once again. Devastated, I acknowledged that my incredible patient—the superhero—would not win his battle; that he could not win, because he had a terrible leukemia and because he faced the equally terrible complications of undergoing transplantation. Unlike a Marvel comic, this was real life, and in real life there are no invincible superheroes when it comes to cancer.

Or so I thought. But I quickly found that his legacy accompanied me daily, ever after. I use his story to discuss the benefits and risks of returning to work and exercising after undergoing transplantation. I speak of the potential devastation of GVHD and the need to be aggressive with prophylaxis and early management. I share parts of his tale with patients who doubt themselves and who fear their own abilities to undergo transplantation. It struck me that although his body failed him, his battle against cancer only reinforced his superhero status. He was a hero because he would not let cancer interfere with who he was or what he stood for; because he made people around him feel safe and protected and empowered them to be brave, to fight their best fight, and to use every tool at their disposal to ensure positive outcomes as often as humanly—even superhumanly—possible.

Image credit: Jonas de los Reyes / Flickr

Reprinted from the Journal of Clinical Oncology