For the past two years, Mandie Snyder, an accountant near Spokane, Washington, has been “monitoring” her daughter. With a handy tech tool known as mSpy, Snyder is able to review her 13-year-old’s text messages, photos, videos, app downloads, and browser history.

She makes no apologies for it. Last summer, she says, she was able to intervene when she discovered her daughter was texting her boyfriend to plan a sexual rendezvous. “I know my daughter isn’t as naïve as I was at her age, with the plethora of ways to socially interact in today’s world,” Snyder says. “As a parent of a teen, this age of technology scares me.”

But while technology might present terrifying new ways for kids to get into trouble, it also provides new ways for parents to watch their every move.

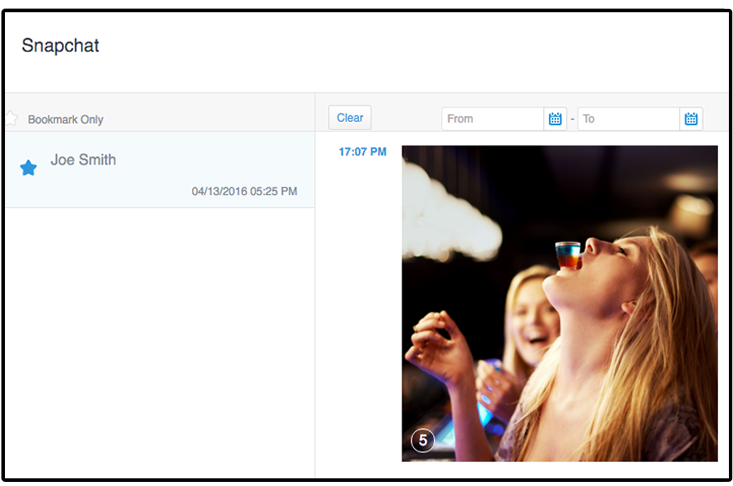

With tracking technologies such as mSpy, Teen Safe, Family Tracker, and others, parents can monitor calls, texts, chats, and social media posts. They can view maps of every location a child (and his phone) has traveled. An app called Mama Bear even sends parents speeding alerts if their kid is traveling too fast in a car.

But there’s a fine line between protection and obsession. The new digital spy tools present parents with a quandary. Adolescence is a critical time in kids’ lives, when they need privacy and a sense of individual space to develop their own identities. It can be almost unbearable for parents to watch their children pull away. But as tempting as it may be for parents to infiltrate the dark corners of their children’s personal lives, there’s good evidence that snooping does more harm than good.

Taking the long view, the goal of parenting is to create a healthy, self-sufficient adult. The process of developing healthy autonomy starts as soon as kids can crawl away from you, says Nancy Darling, a developmental psychologist at Oberlin College. “What’s hard about parenting is balancing the kid’s desire for autonomy with safety concerns,” she says.

Privacy is a key piece of developing that self-sufficiency. “The ability to experience privacy is probably a basic human need that transcends culture,” says Skyler Hawk, a social psychologist who studies adolescent development at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. During adolescence, kids’ brains, bodies, and social lives are changing rapidly. As they experiment with their identities and self-expression, they need space to figure it all out, Hawk says.

Privacy isn’t just important for adolescents, says Sandra Petronio, a professor of communication studies and director of the Communication Privacy Management Center at Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis. It’s their duty. “An adolescent’s main job is to individuate, to move away from being controlled by the parent. One very clear way they do that is in their demand for private space,” she says.

There’s considerable evidence that intruding on kids’ privacy damages the parent-child relationship, says Petronio. “When parents snoop, they show mistrust,” she says. “That overarching need for control really damages the relationship.”

A parent’s desire to spy might have less to do with keeping kids safe, and more to do with a burning desire to lower his or her own anxiety.

And covert spying, Hawk adds, isn’t likely to stay covert for long. Most kids are more tech savvy than their parents. Odds are good they’ll discover those tracking apps and figure out how to hack the system—leaving their location-tracking phone in their locker when they ditch class, or setting up a second (secret) Instagram account.

Unsurprisingly, when kids don’t feel they can trust their parents, they become even more secretive. Hawk saw this effect in a sample of junior-high students in the Netherlands, where feelings about individualism and autonomy are similar to those in the United States. The researchers asked the kids about whether their parents respected their privacy. A year later, the children of snoops reported more secretive behaviors, and their parents reported knowing less about the child’s activities, friends, and whereabouts, compared to other parents.

“We can trace a path over time from feelings of privacy invasion to higher levels of secrecy to parents’ reduced perceptions of knowledge about their children,” Hawk says. “If parents are engaging in highly intrusive behaviors, it is ultimately going to backfire on them.”

The parent-child relationship isn’t the only thing that suffers when a child doesn’t have enough personal space. When kids feel their privacy has been invaded, it can lead to the types of mental health problems that experts call “internalizing” behaviors—things like anxiety, depression, and withdrawal. “There’s a lot of research indicating that kids who grow up with overly intrusive parents are more susceptible to those mental health problems, partly because they undermine the child’s confidence in their abilities to function independently,” says Laurence Steinberg, a professor of psychology at Temple University and author of Age of Opportunity: Lessons From the New Science of Adolescence.

When parents don’t give children privacy to make their own decisions, kids don’t have a chance to learn from those decisions. While parents have an obligation to guide their children and protect them from harm, adolescence is still a time for testing limits, says Judith Smetana, a professor of psychology who studies adolescent-parent relationships at the University of Rochester.

Take alcohol use. Kids who experiment with drinking in adolescence but don’t become heavy drinkers tend to be psychologically healthier than those who never experiment, Smetana says. “I don’t want to condone kids getting into drinking, but we know this is a time of experimentation,” she says. “It’s the nature of adolescence.”

But even when parents know the importance of privacy, it can be hard to figure out where to draw the line. That boundary will look different for every family, even within a single socioeconomic strata or a single neighborhood, says Dalton Conley, a sociologist at Princeton University and author of the 2014 book, Parentology. Conley says he was shocked when he learned a professional colleague spied on her teens with a nanny cam while she was away at a conference. At the same time, he has no qualms checking his own kids’ debit card statements to find out where they’ve been and what they’ve been purchasing. “The technology of parental monitoring has evolved so rapidly, there aren’t clear norms of what’s acceptable,” he says.

When parents snoop, they show mistrust. That overarching need for control really damages the relationship.

Darling, too, has been tempted to dip a toe over the line between independence and privacy. As much as she advocates for giving kids space to develop healthy autonomy, she’s also a parent who worries. She asked her younger son to turn on his Find My iPhone feature so she can track him down if she’s unable to reach him. And when her older son, home from college, didn’t come home one night, “I nosed into his cell phone records so I could call his girlfriend,” she admits. “He was pissed about it, but it was 3 a.m. and I was worried.”

According to Darling, kids are more likely to feel their privacy has been invaded when parents intrude on personal issues, like eavesdropping on a conversation or secretly reading their texts. But most kids realize that parents have legitimate authority over safety issues, such as making rules about drug use and knowing where kids are going after school. “Parents are supposed to know where their children are,” she says.

Yet even safety issues aren’t clear-cut. In most communities, it’s a safe time to be a kid. According to FBI figures, the violent crime rate dropped 48 percent between 1993 and 2011. Child mortality rates are down. Reports of missing children are at record lows.

Nevertheless, some experts say the cultural pressures to keep close tabs on children has never been greater—evidenced by the now-frequent accounts of parents being arrested for letting their children walk alone to school or play unsupervised at the park.

Many experts attribute this shift to the modern media, which regularly delivers terrifying click-bait headlines of abduction and danger. “The media has increased the fear and that fear has turned into restrictions on children, teens, and even young adults,” says Petronio. “It has the potential to undermine the development of the array of skills [young people] need to become independent adults.”

Certainly, some kids live in dangerous neighborhoods. And those kids seem to do better with stricter parental monitoring. A study by researchers at the University of Virginia, for instance, found that for kids in middle-class neighborhoods classified as “low risk,” those whose mothers undermined their autonomy had worse parental relationships and worse social functioning with their peers. But kids in lower-income, higher-risk families reported better relationships with their moms, and exhibited less problem behavior, when their mothers were more authoritarian.

But in many communities, a parent’s desire to spy might have less to do with keeping kids safe, and more to do with a burning desire to lower his or her own anxiety. “The bottom line is that if you’re trying to satisfy your need to know, because you have a low tolerance for ambiguity, you don’t give your child a place to learn how to make better decisions,” Petronio says.

Hawk’s research shows that parents who snoop tend to have less confidence in their parenting abilities, more anxiety about their relationship with their child, and more worries—often unfounded—about their child’s behavior. “Based on my research, I think snooping might say as much about the parent’s adjustment as it does about the child’s—maybe even more so,” he says.

When it comes to establishing healthy boundaries, psychologists say, good communication trumps snooping, and kids who choose to share more with their parents tend to be better adjusted. “Ultimately, the best way to know what is going on with your child is for them to tell you what is going on,” Hawk says.

Some parents say monitoring improves communication with their kids. Snyder says using a tracking app on her daughter’s phone has acted as a launch pad to discuss issues like sex, drugs, suicide, and friends. “Because I read the conversations she has with friends, we can have impromptu conversations about what’s going on in her life,” Snyder says. “I don’t believe we would have such an open and respectful relationship without mSpy’s assistance.”

Still, it’s probably safe to say that most parents who download spy apps aren’t doing it to have quality conversations with their kids. Clearly, privacy and personal space are important for helping kids become healthy adults. Now that it’s easier than ever to invade that privacy, parents have some hard questions to ask themselves each time they’re tempted to cross that line.

Kirsten Weir is a freelance science writer in Minneapolis.

The lead photocollage was created from an image from Larry Bray / Getty Images