When she was a practicing occupational therapist, Elizabeth Fain started noticing something odd in her clinic: Her patients were weak. More specifically, their grip strengths, recorded via a hand-held dynamometer, were “not anywhere close to the norms” that had been established back in the 1980s.

Fain knew that physical activity levels and hand-use patterns had changed a lot since then. Jobs had become increasingly automated, the professional and service sectors had grown, all sorts of measures of physical activity (like the likelihood that a child walks to school1) had declined, and the personal computer age had dawned. But to see the numbers decline so steeply and quickly was still a surprise, and not just to her.

Unlike most findings in the sleepy field of occupational therapy, her findings, which were published last year in the Journal of Hand Therapy, touched off a media firestorm, as the revelation seemed to encapsulate any number of smoldering fears in one handy conflagration: The loss of human potential in the face of automation, of our increasing time spent on smartphones and other devices, the erosion of our masculine norms,2 of the fragility and general shiftlessness of millennials. Even taking into account the cautionary statistical notes—that the sample sizes of the 1980s studies were not huge, that Fain’s study was mostly college students—the idea of a loss in human strength, expressed through a statistical measure hardly anyone had previously heard of, seemed to hint at some latter-day version of degeneration.

That message was reinforced by the sheer predictive power of grip strength. In a study published in 2015 in The Lancet, the health outcomes of nearly 140,000 people across 17 countries were tracked over four years, via a variety of measures—including grip strength.3 Grip strength was not only “inversely associated with all-cause mortality”—every 5 kilogram (kg) decrement in grip strength was associated with a 17 percent risk increase—but as the team, led by McMaster University professor of medicine Darryl Leong, noted: “Grip strength was a stronger predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than systolic blood pressure.”

Gripping is part of a long story in which we have been getting weaker for millions of years.

Grip strength has even been found to be correlated more robustly with “ageing markers” than chronological aging itself.4 It has become a key method of diagnosing sarcopenia, the loss of muscle mass associated with aging.5 Low grip strength has been linked to longer hospital stays,6 and in a study of hospitalized cancer patients, it was linked to a “an approximate 3-fold decrease in probability of discharge alive.”7 In older subjects, lower grip strength has even been linked with declines in cognitive performance.8

“I’ve seen people refer to it as a ‘will-to-live’ meter,” says Richard Bohannon, a professor of health studies at North Carolina’s Campbell University. Grip strength, he suggests, is not necessarily an overall indicator of health, nor is it causative—if you start building your grip strength now it does not ensure you will live longer—“but it is related to important things.” What’s more, it’s non-invasive, and inexpensive to measure. Bohannon notes that in his home-care practice, a grip strength test is now de rigueur. “I use it in basically all of my patients,” he says. “It gives you an overall sense of their status, and high grip strength is better than low grip strength.”

The argument seemed to line up neatly. We are raising a generation of weaklings, more prone to everything from premature aging to mental disorders. Or is the opposite true? Is this just the latest step in the age-old weakening of our species as we emerged from the trees and built up civilization?

Pound per pound, babies are remarkably strong. The parent learns this the first time they proffer their finger. In a famous series of experiments in the late 19th century—of the sort one can scarcely imagine today—Louis Robinson, a surgeon at a children’s hospital in England, tested some 60 infants—many within an hour of birth—by having them hang from a suspended “walking stick.” With only two exceptions, according to one report, the infants were able to hang on, sustaining “the weight of their body for at least ten seconds.”9 Many could do it for upward of a minute. In a later-published photograph, Robinson swapped out the bar for a tree branch, to bring home his whole point: Our “arboreal ancestry.”

This idea—that we are born to brachiate (or swing through trees)—lurks behind the peculiar power of grip strength. “From an evolutionary perspective,” note the authors of a study in Evolution and Human Behavior, “it is interesting to ask why [hand-grip strength] would be such a ubiquitous measure of human health and vitality.”10 Strong hands helped keep us in the trees—in other words, alive (to this day, heavier birth weight is correlated with higher grip strength11). We came down, but then our hands adapted to new uses, the sorts of things that made us human.

As the evolutionary biologist Mary Marzke argues, our hands today were literally shaped around millions of years of using and making tools (our cerebral hemispheres, notes John Napier, author of the classic study Hands, expanded as our tool making did). The human hand became an almost perfect gripping machine. That long opposable thumb, enabling what has been termed the “power grip” and the “precision grip,” looms most obvious. But consider also the Papillary ridges, those tougher, thicker parts of the skin, found on the human heel, but also on the human palm—a vestigial souvenir from our time as quadrupeds. Their placement, as Napier writes in Hands, “corresponds with the principal areas of gripping and weight bearing, where they serve very much the same function as the treads on an automobile tire.” Eccrine glands perfectly line the papillary ridge, Napier notes, providing a grip-enhancing “lubrication system.” This sort of “frictional adaptation” does not kick in until we are around 2, writes Frank Wilson in The Hand (before then, we just grip harder).

Gripping, then, is a deep part of our biology and evolution as a species. It’s also part of a long story in which we have been getting weaker for millions of years, largely because of a decline in physical activity. The human skeleton, for example, is “relatively gracile” (weak) compared to hominoids.12 Those infants tested by Robinson, stout hangers-on though they may have been, can hardly compete with infant monkeys, who can hang on for upward of a half hour. Why? Because they need to. “Modern infants,” as one researcher notes, “as well as their fairly recent human antecedents, do not need to hang on with their hands and feet from the moment of birth.”13

It’s easy to be troubled by a nearly 20 percent decrease in grip strength, especially given that it happened in one generation.

In other words, our hands have changed as our environment has changed. Studies done in traditional societies have shown that correlations between grip strength and hunting success have declined. “Perhaps strength become becomes less of an important determinant of hunting ability,” writes one researcher, “as a population undergoes acculturation and the range of variation in skill within the population increases.”14 In a world where one can get more done with a smartphone than a hand-axe, our hands seem to be on the move, as they have always been.

Witness, for example, the palmaris longus, the tendon that connects your forearm to your palm (and which becomes visible, in many people, when you flex your palm upward). The muscle, according to one hypothesis, was once important for tasks like brachiation, but has been slowly declining in humans. In some cultures some 63 percent of people no longer have it. As one group of researchers notes, “if human evolution continues along similar lines wherein the muscle belly [the sum of all the muscle fibers] continues to phylogenetically reduce, it is expected that this muscle will eventually not be found in humans.”15

This inverse correlation between grip strength and civilization has been both celebrated and debated over the centuries. Jean-Jacques Rousseau saw in civilization a weakening of “all the vigor of which the human species was capable.” The French explorer François Perón, intent on discrediting Rousseau’s argument, brought an early Régnier dynamometer to Tasmania to test the strength of “savage man” against his own sailors. The more “savage” the people, Peron reported, contra Rousseau, the weaker they were. He took his grip strength tests as conclusive proof against the then-fashionable argument “that the physical degeneration of man follows the perfection of civilization.”

Which is the correct interpretation of the great modern weakening? There has certainly been an across-the-board change in the usefulness of grip strength over a very short period of time, which Fain acknowledges. “An auto mechanic would have a higher grip strength than a salesman, typically,” Fain notes. But even a contemporary auto mechanic, she suspects, would have a lower grip strength than their 1985 equivalent. “A lot of their tools have changed to automate things,” she says. “To change a tire, they used to do that with mechanical force, but now they have an air gun to turn those nuts and bolts for them.” We can even now read of pro athletes unable to complete a single pull-up.16

Coincidentally, Fain grew up on a farm, where manual labor was common. She jokes that no one ever wanted to thumb-wrestle her brother. His hands, grown strong from milking cows, were like steel pincers. I came of age in the 1980s, so I also belong to the norm group that posted the strong numbers in Fain’s comparison. But I am hardly the picture of a lumberjack. My days are mostly devoted to sitting at my keyboard, researching and writing articles like this one.

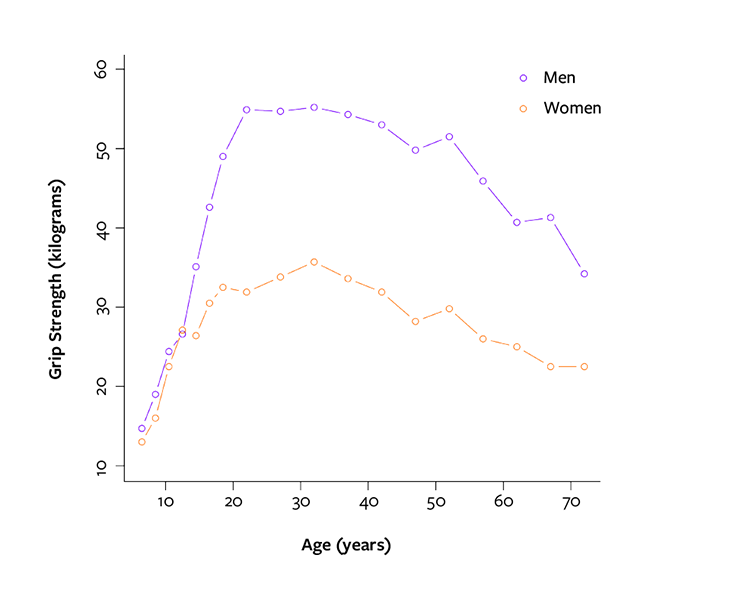

Curious about what that all of that means for my own grip strength, I went out and bought a Jamar Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer, which is favored by clinicians. My strength rang in at nearly 62 kgs which, according to a chart of normative grip strengths in the Jamar’s manual, was above the mean for males 45-49, but not hugely outside the standard deviation. In that data, my age group did worse than the 20-24 age group, like you’d expect.

What was surprising was that my grip strength came in at 40 percent above a group of contemporary male college students that Fain measured last year. She found that a group of males aged 20-24—ages that had produced some of the peak mean grip strength scores in the 1980s tests—had a mean grip strength of just 44.7 kgs, well below my own and far below the same cohort in the 1980s, whose mean was in the low 50s. There were also significant declines in female grip strength.

It’s easy to be troubled by a nearly 20 percent decrease in grip strength, especially given that it happened in one generation, a blink of an eye compared to evolutionary time scales. But to denounce it as a sign of culture denigration is to try to fix culture as natural, when in reality it is as shifting as our bodies themselves. Should we decry the withering away of muscle, if our bodies prosper in the environment that surrounds them? The last 10 years have also seen a dramatic increase in myopia, most likely because we spend more time indoors and because of the type of work we do. But should we stop reading? Should we swing from the trees to get our grip strength back? Even if we got our paleo hands back, what good would they do us in the modern world?

And if a measure like grip strength were truly so robust a health indicator, shouldn’t life spans be declining as (and if) grip strength was? Bohannon warns me, “I would not interpret small declines in grip strength as indicative of decreasing health.” As he notes, you have to get pretty low in the statistical profile—“in the lowest quartile or tertile or below the median of a tested population”—before you start to get into increased mortality risk territory.

Another problem is to fixate (like those 19th-century explorers did) on grip strength itself as a flawless indicator of health (or anything else). After all, as the anthropologist Michael Gurven (who has measured grip strength among the Tsimane’ Amerindians of the Bolivian Amazon, among other groups) reminded me, “women have lower grip strength than men, yet live longer and have lower mortality than men at most ages.” He also advised me not to discount the motivational factor in grip strength testing: “Offering a prize to folks does increase their scores.” Perhaps I was so intent on proving that “I still had it” against my millennial counterparts that I simply tried harder.

Despite all these caveats, there is a larger narrative into which declining grip strength fits neatly. Daniel Lieberman, Harvard University paleoanthropologist, and author of The Story of the Human Body, tells me that “overall strength and fitness are declining in the post-industrial world, and the epidemiological transition is increasing lifespan.” But, he noted, “those two trends are occurring for totally different reasons.”

We tend to fixate on the measure of lifespan, but overlook morbidity. Here, Lieberman says, the data are unequivocal. “As we are living longer,” he says, people “are also suffering from much longer periods of chronical illness as they age.” People may be living longer, due to advances in pharmaceuticals or medical care, but as he asks, “is she/he healthy?” Health, he says, “is not just life expectancy.”

Our weakening grips are, if nothing else, a corollary of an increasingly sick population. So, by all means, go to the gym, not to turn back the evolutionary tide, but for your own well-being. Evolution, as Lieberman reminds us in The Story of the Human Body, is just about passing your genes, not ensuring a long and healthy life. “From an evolutionary perspective, there is no such thing as optimal health.” Creating that definition is up to you.

Tom Vanderbilt is a regular Nautilus contributor and the author of, most recently, You May Also Like: Taste in an Age of Endless Choice.

References

1. Mackett, R.L. Children’s travel behaviour and its health implications. Transport Policy 26, 66-72 (2013).

2. French, D. Men Are Getting Weaker—Because We’re Not Raising Men National Review http://www.nationalreview.com (2016).

3. Leong, D.P., et al. Prognostic value of grip strength: findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. The Lancet 386, 266-273 (2015).

4. Syddall, H., Cooper, C., Martin, F., Briggs, R., & Aihie Sayer, A. Is grip strength a useful single marker of frailty?” Age and Ageing 32, 650-656 (2003).

5. Cruz-Jentoft, A.J., et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European working group on Sarcopenia in older people. Age and Ageing 39, 412–23 (2010).

6. Bohannon, R.W. Muscle strength: clinical and prognostic value of hand-grip dynamometry. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care 18, 465-470 (2015).

7. Mendes, J., Alves, P., & Amaral, T.F. Comparison of nutritional status assessment parameters in predicting length of hospital stay in cancer patients. Clinical Nutrition 33, 466-470 (2014).

8. Björk, M.P., Johansson, B., & Hassing, L.B. I forgot when I lost my grip—strong associations between cognition and grip strength in level of performance and change across time in relation to impending death. Neurobiology of Aging 38, 68-72 (2016).

9. Darwinism in the Nursery Southland Times (1892). https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ST18920123.2.30

10. Gallup, A., White, D.D., & Gallup, G.G. Handgrip strength predicts sexual behavior, body morphology, and aggression in male collage students. Evolution & Human Behavior 28, 423-429 (2007).

11. Dodds, R., et al. Does a heavy baby become a strong child? Grip strength at 4 years in relation to birthweight.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 64, A11-A12 (2010).

12. Ryan, T.M. & Shaw, C.N. Gracility of the modern Homo sapiens, skeleton is the result of decreased biomechanical loading. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 372-377 (2014).

13. Futagi, Y., Toribe, Y., & Suzuki, Y. The grasp reflex and moro reflex in infants: Hierarchy of primitive reflex responses. International Journal of Pediatrics Article ID 191562 (2012).

14. Walker, R., Haan, M., Kaplan, H., & Mcmillan, G. Age-dependency in hunting ability among the Ache of Eastern Paraguay. Journal of Human Evolution 42, 639-657 (2002).

15. Capdarest-Arest, N., Gonzalez, J.P., & Türker, T. Hypotheses for ongoing evolution of muscles of the upper extremity. Medical Hypothesis 82, 452-456 (2014).