With suburbs, architects gave adults just what they wanted: Affordable houses with lawns and garages, homes where children can be raised free from the threats of urban and natural life. By this measure, suburbs are a success—as long as you can stomach monotony. Suburban streets in Phoenix, Ariz. might as well be those in Alberta, Canada or Florida’s everglades.

The monotony does more than crush souls. It takes a lot of energy to maintain a stubborn uniformity amid a range of natural environments. Green lawns in Arizona’s Sonoran desert sap limited reservoirs, and heat runs full-blast for most of the year in Wisconsin’s old wooden houses. Sam Rashkin, author of the 2010 book Retooling the U.S. Housing Industry and a chief architect at the U.S. Department of Energy in Washington, D.C., says things need to change. “The thing we can’t keep doing is building suburban developments that don’t work,” Rashkin says. Today’s suburbs waste too much energy, pollute the environment and their inhabitants, and are strikingly dull.

As environmentalists strive to build more eco-friendly burbs, they are producing an unexpected benefit: Their greener houses lend a visual diversity to a residential model that has remained largely unchanged since the 1950s. Green houses are developed with their surroundings in mind, which means that green suburbs may one day vary dramatically from one part of the world to the next. Parents would need to explain to their children the irony in films like The ’Burbs, SubUrbia, and Heathers that mock the suppressed individuality of cookie-cutter neighborhoods.

One way the Department of Energy tackles the shortcomings of modern-day suburbia is to host a “Solar Decathlon” housing competition. The competition challenges architecture and engineering students to build houses that generate most of the energy their inhabitants require for basic needs, like lights, heating, and cooling. Since the competition began in 2002, no two entrees have looked alike. Rashkin says the challenge seeks to answer the question, “What would housing look like if we applied the most advanced solutions we could?”

In wooded regions, houses might meld with the forests surrounding them. The winning team this year, a group from Austria, constructed their abode out of oak and silver fir trees, which flourish in western and southern Austria. Wood from the Austrian Spruce lines the outside of the house. Meanwhile, a team from Stanford University in California salvaged Redwood and Douglas fir boards from old homes in the Bay Area, dating back to a time when home-builders commonly relied on local materials.

Tomorrow’s suburbs might look more fluid if curtains take hold in cool climates. Teflon-coated curtains drape over the house built by the Austrian team. Snow covers parts of Austria from November through May, and the curtains both trap heat within the house and weatherproof the wood. Thousands of slits in the Teflon allow light to scatter into the house through floor-to-ceiling glass windows so that sunshine wards off the winter doldrums. Another team protects homeowners from cold desert evenings with a white vinyl quilt that makes their trailer-sized home look as if it’s dressed in a puffy jacket.

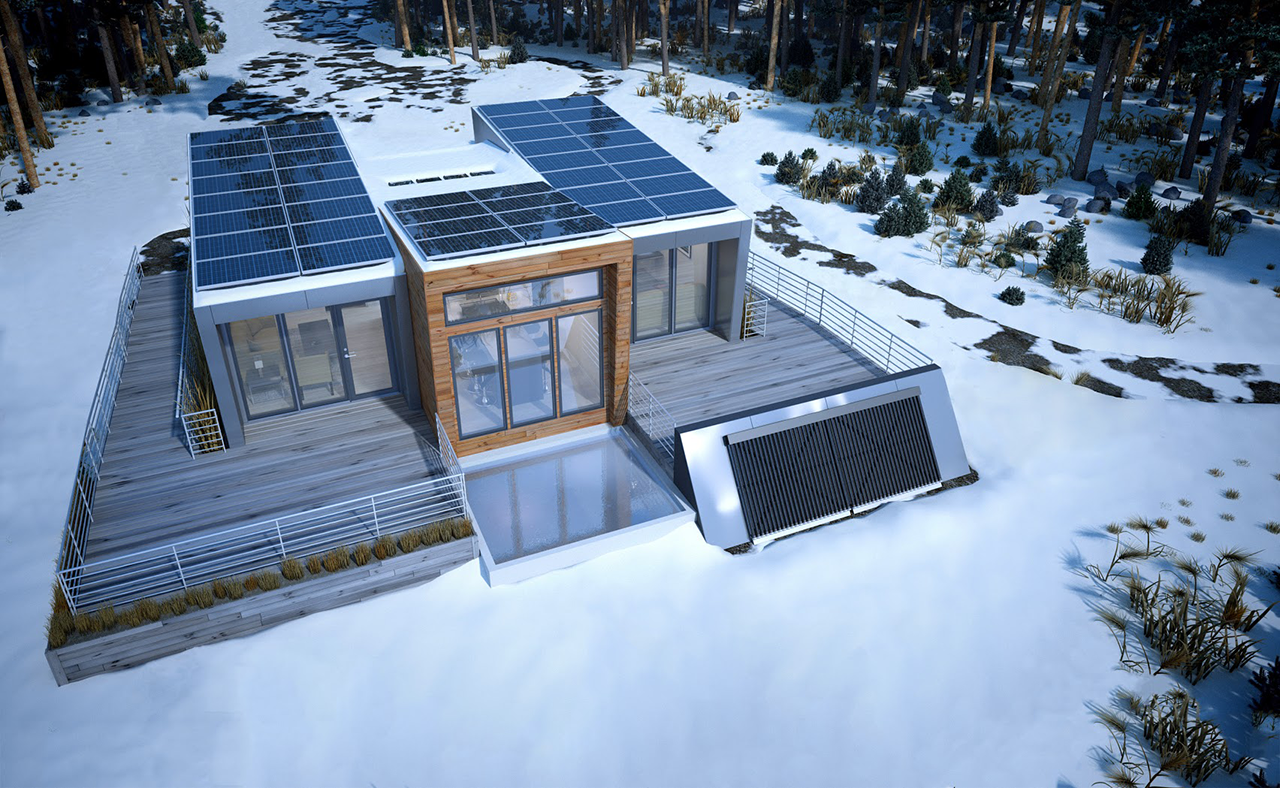

Nearly all of the houses in the Challenge feature solar panel roofs. But a dwelling from frosty Canada takes maximum advantage of Alberta’s sunny skies by also harnessing sunshine with a board comprised of forty glass tubes beside the house. Within each glass tube is a copper pipe filled with liquid heated from the sun. Water stored in a tank within the house circulates though the glass tubes, picking up heat from the pipes and returning to the tank where people can use it to shower—no furnace required.

Houses in rainy regions might one day come with grassy rooftop gardens that absorb precipitation and prevent heat from within the house from escaping. And suburbs in arid environments might use gardens to shade their residents. A team from Arizona replaced typical solid walls with a garden of adult-sized succulents beside western-facing windows to block the sun without trapping heat inside. In addition, the house is surrounded by small tanks that collect rainwater used to maintain the gardens.

Scientists predict that hurricanes, droughts, and other severe weather events will increase in frequency as the planet warms, so tomorrow’s suburbs must be prepared for climactic emergencies. “Disaster resistance is absolutely critical to everything we are doing,” Rashkin says. A home built by a team from Indiana and Kentucky, states with frequent tornadoes, reinforced their home with a steel and wooden frame. The bathroom of the house doubled as a “safe room” with a steel door, bulletproof glass windows, and walls reinforced with steel strips that prevented the wood from ripping apart under pressure.

Houses built in the Southeastern United States might be made of concrete with steel framing, says Rashkin. But rather than making them twister-proof, the steel would thwart wood-eating termites that lead typical homeowners to spend hundreds of dollars on toxic treatments every year. Shelters in humid locales would be made of materials that resist flood and moisture damage. Those near cities might include indoor “living walls” lined with plants that naturally filter the air inside.

Suburbs were originally built to satisfy the demands of fleeing city-dwellers. Today, too, the market will dictate whether these sustainable houses become the future. Rashkin says the transformation will happen when homeowners learn how much money they’ll save on energy, water, and maintenance bills. But once they move in, he says the houses will also feel right on a visceral level. The angst of living in impersonal suburbs detached from their surroundings will dissipate. “I have no doubts,” Rashkin says, “this is the future of housing.”

Adrienne Berard’s writing appeared in Narratively, The Real Deal, The Star Tribune, The Columbus Dispatch, and other publications. Her book, When Yellow was Black: The untold story of the first fight for desegregation in Southern schools will be published by Beacon Press in 2015.