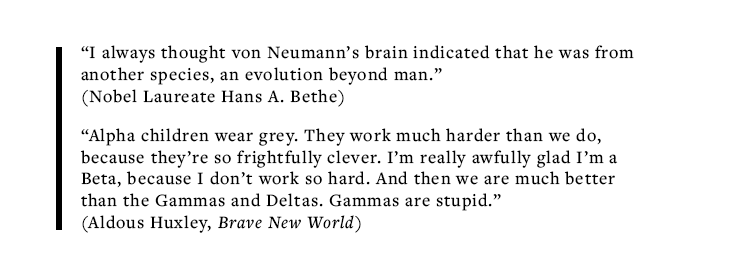

Lev Landau, a Nobelist and one of the fathers of a great school of Soviet physics, had a logarithmic scale for ranking theorists, from 1 to 5. A physicist in the first class had ten times the impact of someone in the second class, and so on. He modestly ranked himself as 2.5 until late in life, when he became a 2. In the first class were Heisenberg, Bohr, and Dirac among a few others. Einstein was a 0.5!

My friends in the humanities, or other areas of science like biology, are astonished and disturbed that physicists and mathematicians (substitute the polymathic von Neumann for Einstein) might think in this essentially hierarchical way. Apparently, differences in ability are not manifested so clearly in those fields. But I find Landau’s scheme appropriate: There are many physicists whose contributions I cannot imagine having made.

I have even come to believe that Landau’s scale could, in principle, be extended well below Einstein’s 0.5. The genetic study of cognitive ability suggests that there exist today variations in human DNA which, if combined in an ideal fashion, could lead to individuals with intelligence that is qualitatively higher than has ever existed on Earth: Crudely speaking, IQs of order 1,000, if the scale were to continue to have meaning.

In Daniel Keyes’ novel Flowers for Algernon, a mentally challenged adult called Charlie Gordon receives an experimental treatment to raise his IQ from 60 to somewhere in the neighborhood of 200. He is transformed from a bakery worker who is taken advantage of by his friends, to a genius with an effortless perception of the world’s hidden connections. “I’m living at a peak of clarity and beauty I never knew existed,” Charlie writes. “There is no greater joy than the burst of solution to a problem… This is beauty, love, and truth all rolled into one. This is joy.” The contrast between a super-intelligence and today’s average IQ of 100 would be greater still.

The possibility of super-intelligence follows directly from the genetic basis of intelligence. Characteristics like height and cognitive ability are controlled by thousands of genes, each of small effect. A rough lower bound on the number of common genetic variants affecting each trait can be deduced from the positive or negative effect on the trait (measured in inches of height or IQ points) of already discovered gene variants, called alleles.

The Social Science Genome Association Consortium, an international collaboration involving dozens of university labs, has identified a handful of regions of human DNA that affect cognitive ability. They have shown that a handful of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in human DNA are statistically correlated with intelligence, even after correction for multiple testing of 1 million independent DNA regions, in a sample of over 100,000 individuals.

If only a small number of genes controlled cognition, then each of the gene variants should have altered IQ by a large chunk—about 15 points of variation between two individuals. But the largest effect size researchers have been able to detect thus far is less than a single point of IQ. Larger effect sizes would have been much easier to detect, but have not been seen.

This means that there must be at least thousands of IQ alleles to account for the actual variation seen in the general population. A more sophisticated analysis (with large error bars) yields an estimate of perhaps 10,000 in total.1

Each genetic variant slightly increases or decreases cognitive ability. Because it is determined by many small additive effects, cognitive ability is normally distributed, following the familiar bell-shaped curve, with more people in the middle than in the tails. A person with more than the average number of positive (IQ-increasing) variants will be above average in ability. The number of positive alleles above the population average required to raise the trait value by a standard deviation—that is, 15 points—is proportional to the square root of the number of variants, or about 100. In a nutshell, 100 or so additional positive variants could raise IQ by 15 points.

Given that there are many thousands of potential positive variants, the implication is clear: If a human being could be engineered to have the positive version of each causal variant, they might exhibit cognitive ability which is roughly 100 standard deviations above average. This corresponds to more than 1,000 IQ points.

It is not at all clear that IQ scores have any meaning in this range. However, we can be confident that, whatever it means, ability of this kind would far exceed the maximum ability among the approximately 100 billion total individuals who have ever lived. We can imagine savant-like capabilities that, in a maximal type, might be present all at once: nearly perfect recall of images and language; super-fast thinking and calculation; powerful geometric visualization, even in higher dimensions; the ability to execute multiple analyses or trains of thought in parallel at the same time; the list goes on. Charlie Gordon, squared.

To achieve this maximal type would require direct editing of the human genome, ensuring the favorable genetic variant at each of 10,000 loci. Optimistically, this might someday be possible with gene editing technologies similar to the recently discovered CRISPR/Cas system that has led to a revolution in genetic engineering in just the past year or two. Harvard genomicist George Church has even suggested that CRISPR will allow the resurrection of mammoths through the selective editing of Asian elephant embryo genomes. Assuming Church is right, we should add super-geniuses to mammoths on the list of wonders to be produced in the new genomic age.

Some of the assumptions behind the prediction of 1,000 IQs are the subject of ongoing debate. In some quarters, the very idea of a quantification of intelligence is contentious.

In his autobiographical book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, the Nobel Prize winning physicist Richard Feynman dedicated an entire chapter to his quest to avoid the humanities, called “Always Trying to Escape.” As a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he says, “I was interested only in science; I was not good at anything else.”

The sentiment is a familiar one: Common wisdom sometimes says that people who are good at math are not so good with words, and vice versa. This distinction has affected how we understand genius, suggesting it is an endowment of one particular faculty of the brain, and not a general superlative of the whole brain itself. This in turn makes the idea of apples-to-apples comparisons of intelligence moot, and the very idea of a 1,000 IQ problematic.

The sentiment is a familiar one: Common wisdom sometimes says that people who are good at math are not so good with words, and vice versa. This distinction has affected how we understand genius, suggesting it is an endowment of one particular faculty of the brain, and not a general superlative of the whole brain itself. This in turn makes the idea of apples-to-apples comparisons of intelligence moot, and the very idea of a 1,000 IQ problematic.

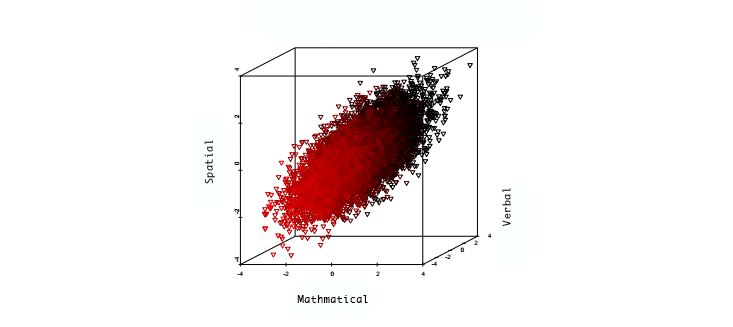

But psychometric studies, which seek to measure the nature of intelligence, paint a different picture. Millions of observations have shown that essentially all “primitive” cognitive abilities—short and long term memory, the use of language, the use of quantities and numbers, the visualization of geometric relationships, pattern recognition, and so on—are positively correlated. The figure below displays graphically the ability scores of a large group of individuals, in areas such as mathematical, verbal, and spatial performance. The space of the graph is not filled uniformly, but instead the points cluster along an ellipsoidal region with a single long (or principal) axis.

These positive correlations between narrow abilities suggest that an individual who is above average in one area (for example, mathematical ability) is more likely to be above average in another (verbal ability). They also suggest a robust and useful method for compressing information concerning cognitive abilities. By projecting the performance of an individual onto the principal axis, we can arrive at a single number measure of cognitive ability results: the general factor g. Well-formulated IQ tests are estimators of g.

Does g predict genius? Consider the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth, a longitudinal study of gifted children identified by testing (using the SAT, which is highly correlated with g) before age 13. All participants were in the top percentile of ability, but the top quintile of that group was at the one in 10,000 level or higher. When surveyed in middle age, it was found that even within this group of gifted individuals, the probability of achievement increased drastically with early test scores. For example, the top quintile group was six times as likely to have been awarded a patent than the lowest quintile. Probability of a STEM doctorate was 18 times larger, and probability of STEM tenure at a top-50 research university was almost eight times larger. It is reasonable to conclude that g represents a meaningful single-number measure of intelligence, allowing for crude but useful apples-to-apples comparisons.

Another assumption behind the 1,000-IQ prediction is that cognitive ability is strongly affected by genetics, and that g is heritable. The evidence for this assumption is quite strong. In fact, behavior geneticist and twins researcher Robert Plomin has argued that “the case for substantial genetic influence on g is stronger than for any other human characteristic.”2

In twin and adoption studies, pairwise IQ correlations are roughly proportional to the degree of kinship, defined as the fraction of genes shared between the two individuals. Only small differences due to family environment were found: Biologically unrelated siblings raised in the same family have almost zero correlation in cognitive ability. These results are consistent over large studies conducted in a variety of locations, including different countries.

In the absence of deprivation, it would seem that genetic effects determine the upper limit to cognitive ability. However, in studies where subjects have experienced a wider range of environmental conditions, such as poverty, malnutrition, or lack of education, heritability estimates can be much smaller. When environmental conditions are unfavorable, individuals do not achieve their full potential (see The Flynn Effect).

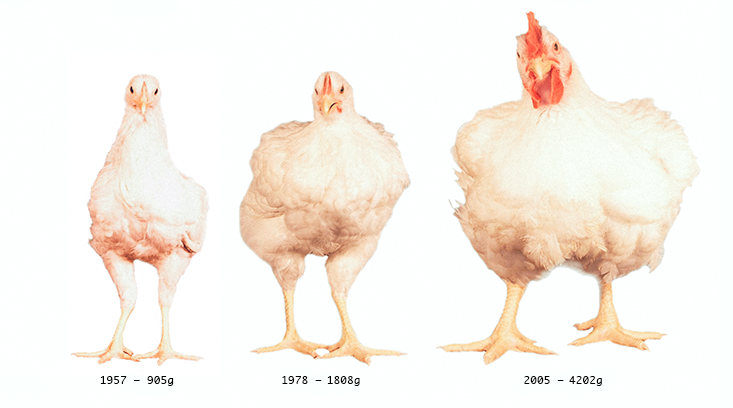

The Flynn effect, named after the philosopher James Flynn, refers to a significant increase in raw cognitive scores over the last 100 years or so—the equivalent of two standard deviations in some cases. This raises a number of thorny issues. Were our ancestors idiots? Is cognitive ability really so malleable under environmental influence (contrary to what has been found in recent twin studies)?

The average person 100 years ago was massively deprived by today’s standards— much more so than we would ever be allowed to reproduce in a modern twin study. United States gross domestic product per capita is eight times higher now, and the average number of years people spend in school has increased dramatically. In the America of 1900, adults had an average of about seven years of schooling, a median of 6.5 years, and 25 percent had completed four years or less. Modern twin and adoption studies only include individuals raised in a much smaller range of environments—almost all participants in recent studies have had legally mandated educations, which in the U.S. includes at least several years of high school.

There is a revealing analogy with height. While taller parents tend to have taller children (i.e., height is heritable), significant gains in average height which mirror the Flynn effect (amounting to an almost +2 standard deviation change) have been observed as nutrition and diet have improved.

Super-intelligence may be a distant prospect, but smaller, still-profound developments are likely in the immediate future. Large data sets of human genomes and their corresponding phenotypes (which are the physical and mental characteristics of the individual) will lead to significant progress in our ability to understand the genetic code—in particular, to predict cognitive ability. Detailed calculations suggest that millions of phenotype-genotype pairs will be required to tease out the genetic architecture, using advanced statistical algorithms. However, given the rapidly falling cost of genotyping, this is likely to happen in the next 10 years or so. If existing heritability estimates are any guide, the accuracy of genomic-based prediction of intelligence could be better than about half a population standard deviation (meaning better than plus or minus 10 IQ points).

Once predictive models are available, they can be used in reproductive applications, ranging from embryo selection (choosing which IVF zygote to implant) to active genetic editing (for example, using CRISPR techniques). In the former case, parents choosing between 10 or so zygotes could improve the IQ of their child by 15 or more IQ points. This might mean the difference between a child who struggles in school, and one who is able to complete a good college degree. Zygote genotyping from single cell extraction is already technically well developed, so the last remaining capability required for embryo selection is complex phenotype prediction. The cost of these procedures would be less than tuition at many private kindergartens, and of course the consequences will extend over a lifetime and beyond.

The corresponding ethical issues are complex and deserve serious attention in what may be a relatively short interval before these capabilities become a reality. Each society will decide for itself where to draw the line on human genetic engineering, but we can expect a diversity of perspectives. Almost certainly, some countries will allow genetic engineering, thereby opening the door for global elites who can afford to travel for access to reproductive technology. As with most technologies, the rich and powerful will be the first beneficiaries. Eventually, though, I believe many countries will not only legalize human genetic engineering, but even make it a (voluntary) part of their national healthcare systems.

The alternative would be inequality of a kind never before experienced in human history.

Stephen Hsu is Vice-President for Research and Professor of Theoretical Physics at Michigan State University. He is also a scientific advisor to BGI (formerly, Beijing Genomics Institute) and a founder of its Cognitive Genomics Lab.

References

1. Hsu, S.D.H. On the genetic architecture of intelligence and other quantitative traits. Preprint arXiv:1408.3421 (2014).

2. Plomin, R. IQ and human intelligence. The American Journal of Human Genetics 65, 1476-1477 (1999).