In social insects, queens, after their nuptial mating flight, get to lie around and be tended to by their caste of workers. Because the queen’s only job is to make babies and order her workers around, she tends to be much bigger and fatter, and less mobile. But, not so for bumblebees, where the queen is larger but otherwise physically indistinguishable from her workers. In a study published today in PNAS, researchers describe a key difference that sets bumblebee queens apart—their tongues.

In bumblebees (Bombus terrestris), the queens forage intensively as they’re getting their nests set up, but as soon as their workers take over the nectar-gathering job, the queens stop. Wondering what was keeping them from gathering more nectar, engineers from San Yat-Sen University, Georgia Tech, and Beijing Institute of Technology combined forces with a paleobiologist from the Chinese Academy of Sciences to examine bumblebee mouthparts. Prior studies had assumed that the queen’s behavior stemmed from hormonal and energy metabolism changes that kicked in once she started reproducing.

Read more: “Loyalty Nearly Killed My Beehive”

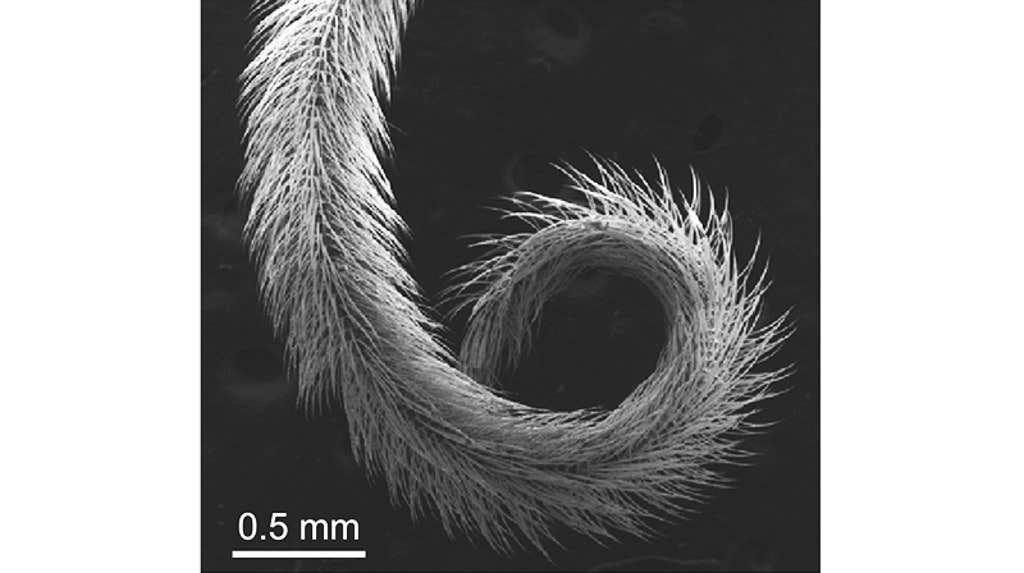

But when they compared bumblebee queens to workers at a micro level, using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the researchers found a difference in their tongues. Bees lap flower nectar using a long proboscis that’s basically a tube wrapped in a hairy tongue. Each segment of the tongue has a ring of slender hairs separated by curved areas (menisci) that trap the liquid nectar. The SEM images revealed that queen bumblebees have more widely spaced hairs than workers, resulting in limited nectar retention in the curved menisci. The queen’s tongue is effectively more porous, which means that queens can lap nectar, but much of it doesn’t stay on their tongues, making them less efficient foragers compared to workers. The study authors postulate that “this physical constraint offers a mechanistic explanation for why queens relinquish foraging once workers emerge, underscoring how subtle deviations in microstructure can influence the division of labor in social insects.”

The microscopic variations in tongue structure may also be relevant in understanding the matching between bee species and flower types. Classically, bee tongue length is interpreted relative to the depth of flower nectaries as an example of coevolution. But porosity of the tongue relative to the viscosity of the nectar may also play a role in bee-flower matchmaking.

So, next time you see a bumblebee buzzing around, be sure to check out its mouthparts. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Linas T / Shutterstock