Ale de la Puente’s moment of clarity arrived in the form of rock, unearthed by a robot 12,000 feet beneath the surface of the Gulf of California. De la Puente, a Mexico City-based multidisciplinary artist, was on a seafaring expedition as part of the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Artist-at-Sea residency program, joining a team of marine geologists, microbiologists, and other scientists aboard the R/V Falkor, exploring the seafloor and occasionally nicking bits of it for research.

While unremarkable in appearance, the rock’s composition and age had the Falkor’s geologists agog. It had been submerged for more than 2 million years, before the remote-controlled underwater vessel, named SuBastian, dug it up. It seemed part of our world and yet so distant and alien; it might as well have been from the moon.

But for de la Puente, what made the moment so poignant was how everyone on the ship interacted with the rock: An engineer gripped it like a football, while the ship’s chef gave it a good sniff, and the geologists approached it with something like reverence. “Everyone interacted with the rock in a different way,” says de la Puente. “As an artist, my job is to create space for different points of view, and to explore why somebody might fall in love with that rock.”

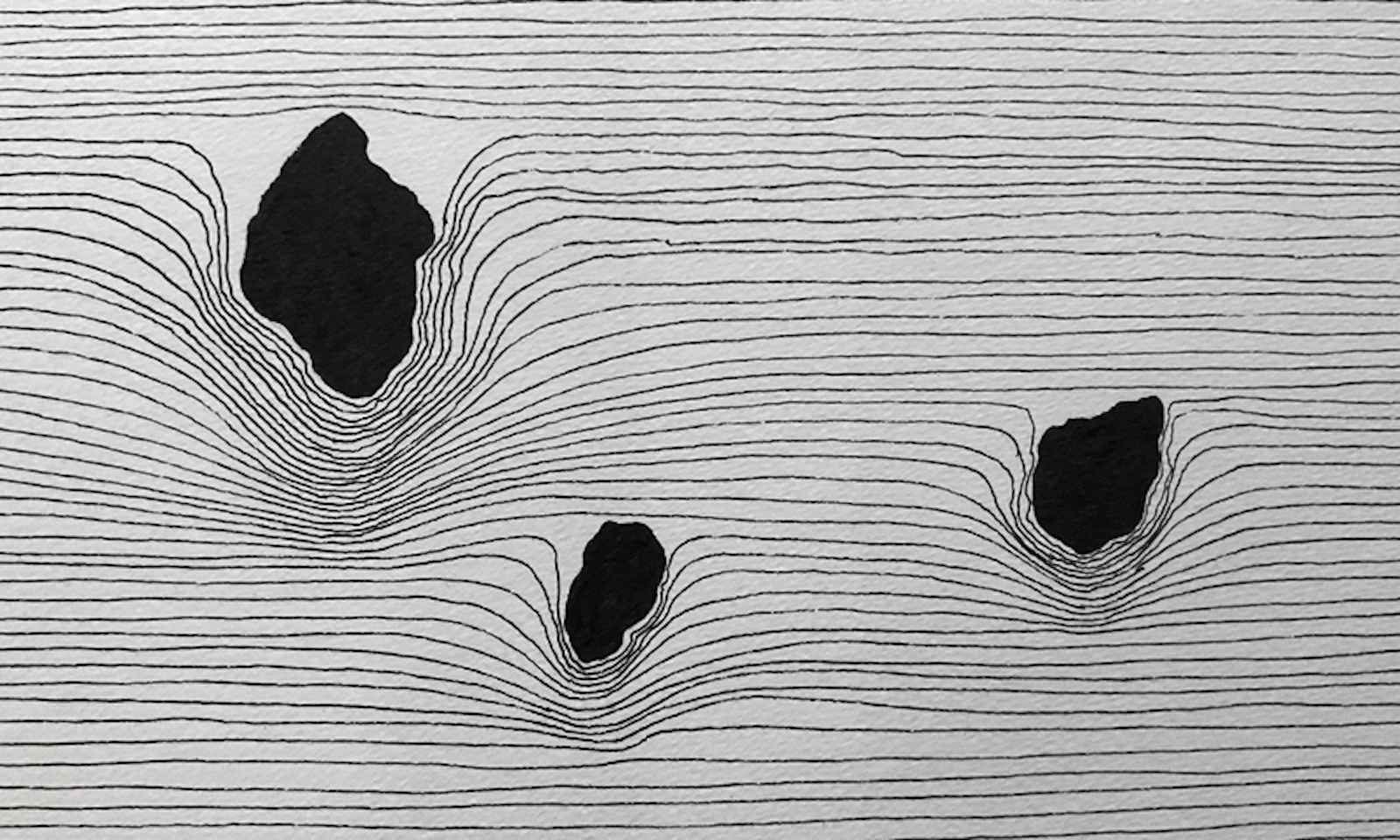

De la Puente created a diptych based on the navigational path of the Falkor as it mapped the ocean floor. Her drawing, Bathymetry Drawings on a Moving Vessel, along with 19 works by other Schmidt Ocean Institute artists, will be on display at the Nautilus Ocean Exhibit at New York City’s Explorer’s Club from March 16 to 20. (Read a short profile of Kishan Munroe, an artist from The Bahamas, included in the exhibition.)

“Focus on the beautiful, the wondrous, the weird—and get the public invested in a positive way.”

The notion of art in dialogue with science inspired Wendy Schmidt, co-founder of Schmidt Ocean Institute (SOI), to launch SOI’s Artist-at-Sea program in 2015. “The idea was to bring artists on board to participate in the science, and to incorporate the science and the data into their art,” says Carlie Wiener, SOI’s director of communications. To date, SOI’s Falkor has hosted 42 artists on expeditions to far-flung locations around the globe. (After a total of 81 expeditions and the mapping of 1.3 million square kilometers of sea floor—and sailing the equivalent of 13 times around the world—the Falkor is being donated to another science organization to make way for a new ship, Falkor Too, with plans to set sail in fall 2022.) “The ocean is so vast and the science so overwhelming, a creative approach can help people digest the science and think about it in different ways,” says Wiener.

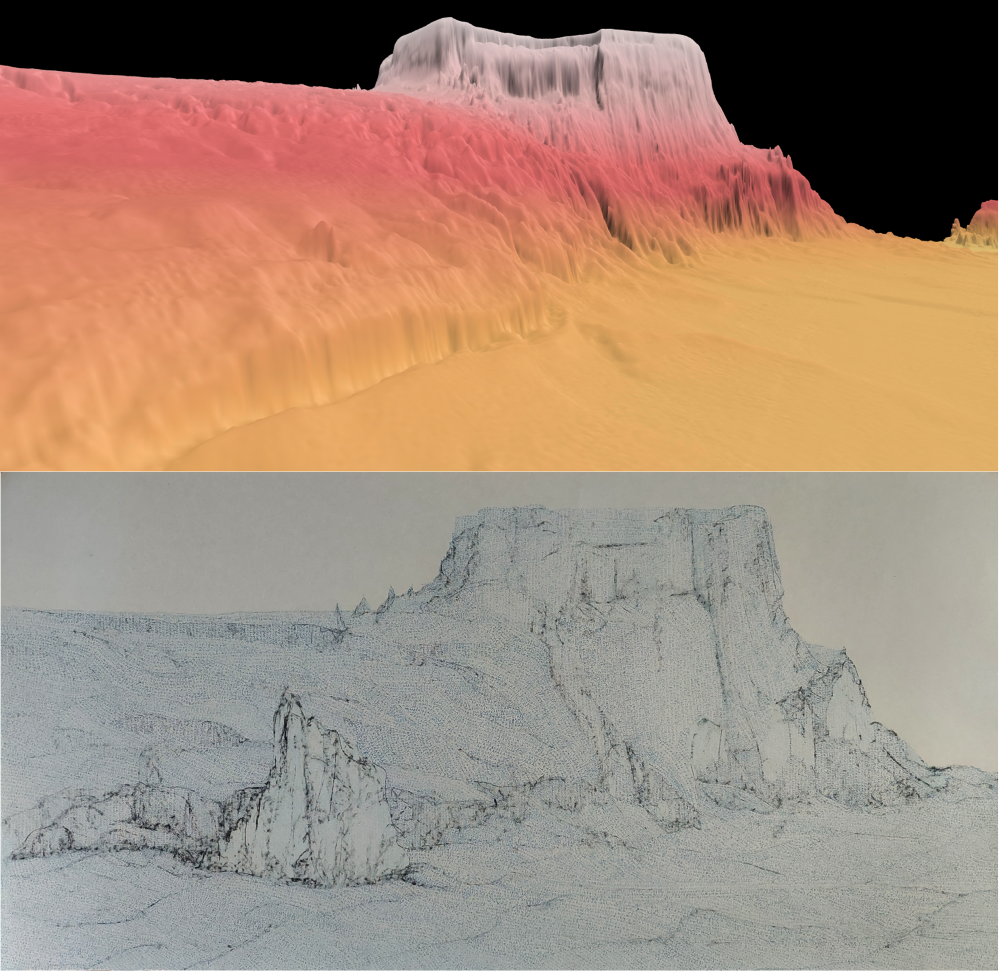

Lea Kannar-Lichtenberger’s artwork embodies the idea of art making science more accessible to non-scientists. The Australian artist joined a Falkor expedition to the Coral Sea in early 2021 and created a painting based on the movements of the Falkor as it mapped the topography, or bathymetry, of the seabed below (Kannar-Lichtenberger’s work will be on view at the Nautilus Ocean Exhibit). The technical mapping process intrigued her: The Falkor’s multibeam sonar system transmits sound “pings” that bounce off the seafloor and return to the ship, which “huge banks of computers process and then spit out as an image we recognize as a landscape,” she says. Back at home, Kannar-Lichtenberger tried to print out a few minutes’ worth of this data on her printer, but the machine balked at the resulting 57,000 pages (!) of hieroglyphics. So she manually cut-and-pasted snippets of code into a Word doc, and incorporated the code into a landscape of a massive underwater mountain entitled Sights Unseen—Cassowary Reef. “Science can be so didactic in the way that it presents its outcomes,” says Kannar-Lichtenberger. “Art helps people emotionally connect with science.”

Not all art is visual, of course. Answer to the Call is a 22-channel sound installation by the Brisbane-based contemporary artist, Taloi Havini, culled in part from recordings she made while on board the Falkor’s 2020 expedition along the southern Great Barrier Reef. “As an artist, I need time and space for research and to formulate ideas, much like scientists do,” says Havini. “I could not have made Answer to the Call without the SOI residency.” Her time at sea helped her think about how ocean conservation requires input from so many different types of people and disciplines, and the first step is to really start paying attention to the ocean. “How can we care for something we don’t have a relationship with?” she asks.

Art can help foster that connection, says Markus Reymann, director of TBA21-Academy, an art and ocean advocacy organization. “Many artists today are trained in critical thinking and research, and so they’re highly attuned to all kinds of injustices like social and environmental justice,” he says. TBA21-Academy has collaborated with SOI on several science art projects, including the exhibition of Havini’s Answer to the Call installation and a new ocean fellowship for indigenous artists. “When artists are exposed to scientific research, they can create alternative possibilities with profound impact by making it accessible to visitors through exhibitions. It’s not art in the service of science, but a relationship that is mutually beneficial.”

Many SOI artists have continued to work with scientists they met aboard the Falkor, says Wiener, demonstrating the success of the program. But there’s more to be done: Ocean scientists should look to other “final frontiers” like space for ideas on how culture can be a vehicle in stoking popular interest in conversation, as opposed to “cramming science down everyone’s throats,” Wiener says. To this end, SOI in collaboration with Nekton recently launched the Ocean Rising program, which explores how arts and culture can make ocean science more accessible and fun. “Space has done an excellent job of this through pop culture and shows like Star Trek, and the oceans have sort of lagged behind that,” Wiener says—and it doesn’t help that with pressing global problems like climate change and overfishing, the ocean can be kind of a bummer. But as with the artist-in-residence program, she says, “you can focus on the beautiful, the wondrous, the weird, and instead get the public invested in a positive way.” ![]()

Lead image: Ale de la Puente’s Bathymetry Drawings on a Moving Vessel. Credit: Courtesy of the Schmidt Ocean Institute.