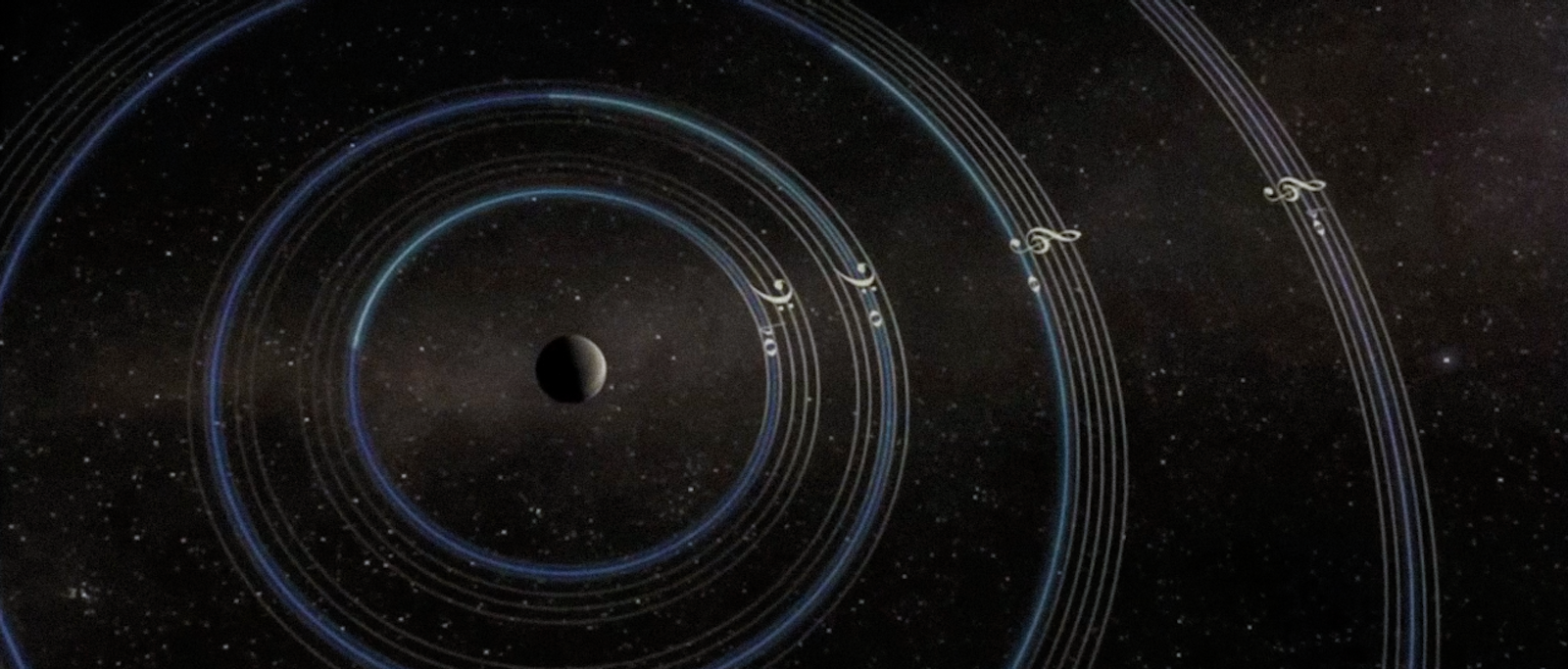

If there really is a music of the spheres, the sound of a fundamental harmony in the universe, it has to be Just Ancient Loops, a 2012 work by composer Michael Harrison. Played on the cello, and complemented by a film created from archival clips and a recreation of Jupiter’s moons in orbit, Just Ancient Loops, glimpsed in the three samples below, propels viewers through time and space, landing them in the present, elated.

Although Just Ancient Loops projects an aura of metaphysics, it was guided by science. Harrison, whose work melds elements of early music, raga, and minimalism, based the score on the fact that musical harmony emerges from mathematical relationships between numbers, spelled out by ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras. Filmmaker Bill Morrison, whose work injects new life into old film clips, recently featured at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, was inspired by a 21st-century investigation into an 18th-century astronomical theory. Bode’s law, named for a German astronomer, states planets and moons orbit their hosts at a mathematically predictable distance. (Although the theory has long been abandoned by astronomers—it doesn’t apply universally to orbiting bodies—it has been revived in a host of recent papers, which have shown some evidence for its calculations in exoplanet systems.) Harrison wrote Just Ancient Loops as a showcase for cellist Maya Beiser, a celebrated champion of contemporary music. She sees the work as an expression of scaling: The work evolves from a single musical pattern or loop into approximately 20 more, which, when performed live, with some of the loops having been prerecorded, blend and soar into something primal.

Those in New York City from October 14 to 17 can see Beiser perform Just Ancient Loops live, with the film, as the conclusion to her program, All Vows, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. (You can watch one of her performances of the complete work here.) Recently the three artists told Nautilus about their individual goals for Just Ancient Loops and how the work became more than each of them had imagined.

Tell us about the title, Michael.

Michael Harrison: “Just” refers to the concept of just intonation; “Ancient” to the ancient musical modes used in the work; and “Loops” to the many modules of sound—the loops—that Maya plays in the piece. Just intonation is a tuning system that was predated by Pythagorean tuning—a spiral of “perfect” fifths that doesn’t return to the same pitch it started from. A perfect fifth in music is a 3-to-2 relationship in sound. When you have two notes in that interval, the frequency of the upper note will be an exact 3-to-2 relationship with the lower note.

For example, if your lower note vibrated at 200 cycles per second, the upper note would be 300 cycles per second. If the lower note was A, at 440 cycles per second, the upper note, E, would be 660 cycles per second. The ear recognizes this simple relationship, and if it’s even a little bit off, your ear will hear that it doesn’t sound right. The most common form of this music that we still know about is Gregorian chant. It’s basically monophonic chant with people singing, and the melodies tend to be in Pythagorean tuning. This type of tuning lasted in the west all the way up through the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance.

Today just intonation has a broader meaning, which is the meaning I ascribe to. The new meaning is any tuning system where the musical intervals are based on whole number relationships. What’s beautiful about this is there are an infinite number of whole number relationships, and so there are infinite numbers of musical intervals. This is extremely pleasing to the ear because the nervous system registers in the brain these whole number proportions as having a type of symmetry and beauty. This is what Plato and Aristotle talked about as representing beauty—not only whole number relationships, but symmetry and proportion. So Just Ancient Loops, which explores the more harmonious aspects of just intonation—most of the piece uses pure fifths and pure thirds, and multiples of them—will sound right in tune to most audience members.

Is this symmetry also reflected in the film?

Harrison: The entire middle section of the film is exploring that concept in the relationship of the orbits of the four moons of Jupiter in direct proportion to musical harmonies. The archival film is about as ancient as you can go, and Bill uses its deterioration to create incredible artistic effects.

Bill Morrison: Michael and I had a great talk about the science behind the music. Because it’s built on this Pythagorean theory of finding whole numbers in nature, it put me in mind of a beautiful PowerPoint that I’d seen by the great film editor Walter Murch. He’s a sort of Renaissance man and has been sampling large amounts of data that show troughs between orbiting planets or satellites tend to sit in the same ratio to one another.

You refer to the film as “Different views of heaven at 24 frames per second.” How did you arrive at that theme, Bill?

Morrison: I was imagining looking at the heavens, and representations of heavens. The opening sequence shows a telescope in the Vatican, and newsreel photographers shooting other newsreel photographers shooting a telescope and people looking at solar eclipses. Later it has a visualization of the Jovian moons and finding a music of the spheres. And the last part is more about evolution and religion and the stories we tell about heaven.

The closing scene of Christ’s ascension, from a 1903 French film, is amazing. Where do you find that old nitrate film footage?

Morrison: I have a relationship with the Library of Congress. I go down there from time to time and they save the things for me that they were otherwise going to toss out. I’ve saved the shot of Christ going up in conflagration of deteriorated nitrate. It was a gem of a piece of footage that I was saving for the right moment, and I had the exalted feeling that it would be right for this project. You get this fine detail with nitrate that you find in no other stock. I find when a frame shares this conflagration of nitrate deterioration with a glass negative that you can only find in old photography to be this really compelling dichotomy on the same frame.

Why do you use old and decayed footage?

Morrison: The use of decay in some sort of metaphysical context is certainly a signature of my work. It’s like this kind of psychedelic earthiness. The decay gives the film an abstract energy. If it was all clean, you would lose the sense that it was printed on something, and it would no longer be a plastic art in the way that it appears. It appears like a painting, or something that we interact with. When the planets in the film were originally filmed, you were just looking at the awesomeness of that planet. It wasn’t about the photography involved, or the chemical process of the film, or that it was stored and waited around 100 years before we saw it. It was about that planet. But now it’s about the vehicle in which the planet needed to be encoded to get to us. So when you see that planet with an old streak on it, or a fold, or some sort of emulsion blip, it becomes about that frame of film as much as about that planet. And that’s why the eclipse footage is so beautiful. It’s the thing that people used to look at as awe-inspiring, and it’s also the way that we captured it and can look at it now. That is also awe-inspiring.

Maya Beiser: For me, the idea of exploring different views of heaven, connecting it to the idea of Pythagoras, and the idea of the spheres, and other scientific ideas that exist about music, takes the whole piece into a spiritual sphere.

What attracts you to the work, Maya?

Beiser: Really what interests me is the connection between ancient acoustic instruments and the technology that exists today, and how we could use that to make the cello explore new territory. What was wonderful about the process was that as we started to build and stack up all these loops and harmonies on top of each other, it became this magical thing. There’s just something so human about the harmonic relationship and what it does to the resonance of the instrument.

What is the experience of playing it?

Beiser: At times I feel like a jazz musician. It has these really intricate rhythmical patterns. And there are moments where it’s very clean and simple. But the clean and simple moments, like the chorale in the middle, are in many ways the most challenging because everything needs to be so pure and pristine, and the intonation has to be just right. There’s something very ancient about it. It’s very ancient and it’s very modern at the same time. In that way it’s very grounding and transformative.

Harrison: The cello is the perfect instrument to play in just intonation. Unlike a piano, the cello does not have a fixed pitch. So you can get any fine gradation of pitch. And the cello has an incredible range. As Maya has done numerous times, she creates a multidimensional performance. You don’t think of a performance as a cello extravaganza, but that’s what she does, and that’s exactly what this piece was intended to do.

Kevin Berger is the features editor at Nautilus.

Video 1, “Genesis”

Source material by arrangement with Moving Image Research Center, University of South Carolina. Special thanks to

Benjamin Singleton, Greg Wilsbacher, and Scott Allen.

Video 2, “Chorale”

Based on research by Walter Murch relating orbits to harmonics. Jovian Moon Visualization by Illinois eDream Institute and Advanced Visualization Lab National Center for Supercomputing Applications University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Research Artist: Robert Patterson; Research Programmer: Stuart Levy; Research Programmer: Alex Betts; and eDream/AVL Director: Donna Cox.

Video 3, “Ascension”

Source material provided by Library of Congress, Packard Campus for Audiovisual Conservation Life and Passion of Christ (1907, France). Directed by Ferdinand Zecca.