Science is a meticulous process, requiring experiment after experiment to arrive at a new truth. So it may come as a surprise to learn that the specific results of science can be illustrated with metaphors, which leave room for interpretation. That’s what we learned from two of Nautilus’ artists, John Hendrix and Tomasz Walenta, whose illustrations have captured the scientific essence of our articles, and whose interpretations have a poetic quality all their own. This week, as we celebrate the launch of the Summer 2014 Nautilus Quarterly, and the opportunity to buy limited-edition prints of Nautilus art, we asked John and Tomasz to talk about the challenges of illustrating science, and about the inspiration behind the illustrations, now prints, for our articles, “Artificial Emotions” and “T.Rex Might be the Thing with Feathers.”

John Hendrix

John grew up in St. Louis, earned an MFA at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where he taught at the Parsons School of Design, and worked as an assistant art director at The New York Times. Today he lives back in his hometown. He has illustrated for Sports Illustrated, Rolling Stone, and The New Yorker, among others. John was the lead artist for our inaugural issue, “What Makes You So Special,” and delivered a host of witty illustrations, including one of hipster Neanderthals. For our article, “Artificial Emotions,” John had to come to grips with the revelation by neurologists and computer scientists that robots may one day have their own “feelings.” As the article’s author Neil Savage explains, “Far from being some inexplicable, ethereal quality of humanity, emotions may be nothing more than an autonomic response to changes in our environment, software programmed into our biological hardware by evolution as a survival response.”

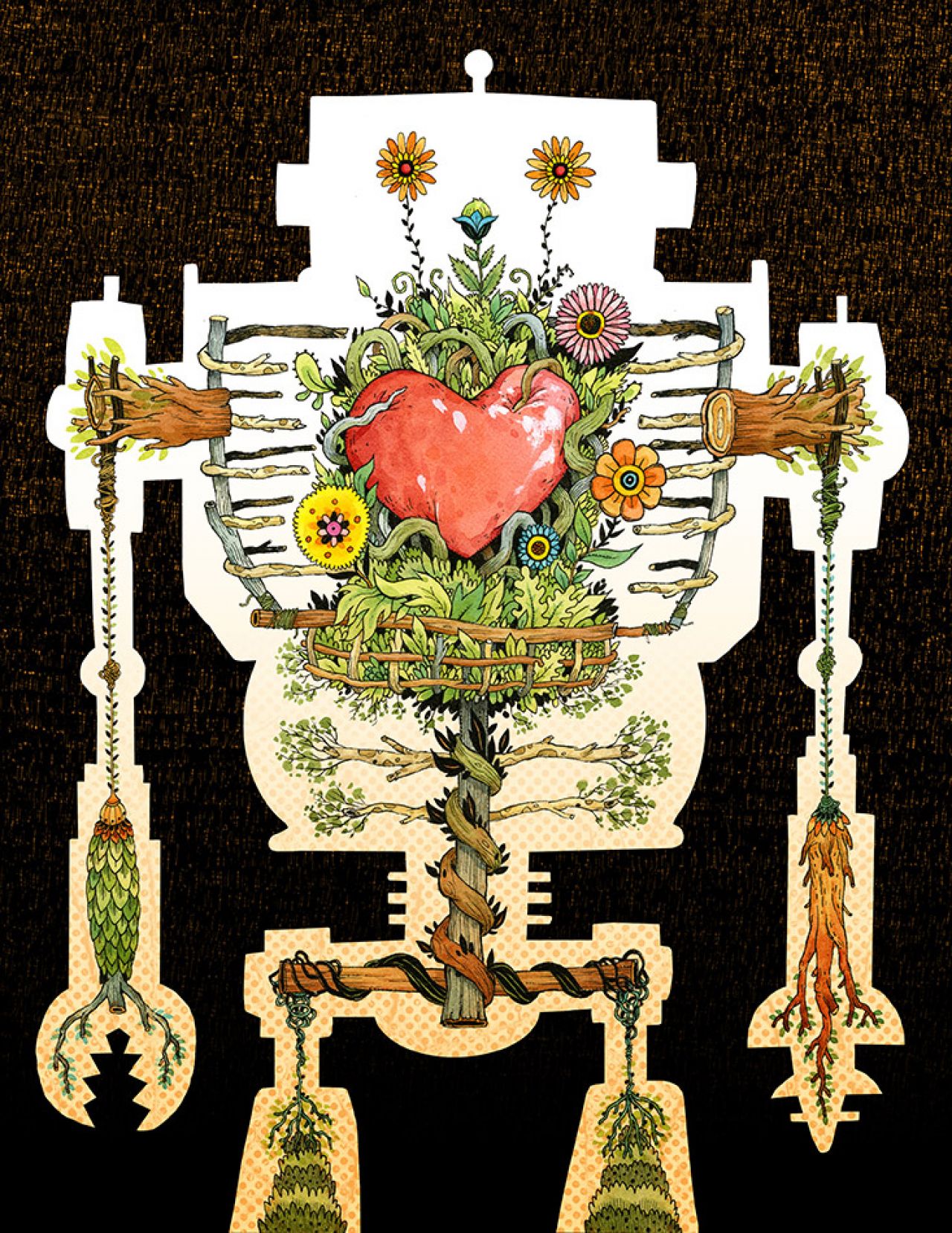

How did you come up with the image for “Artificial Emotions”?

The article was actually a challenge because the idea of robots that have feelings is one of those memes that have been around our culture for so long. We have so many images that relate to that idea, whether it is Terminator or Blade Runner. So when I came up with an image, I wanted to try and not do something like a robot picking a flower. I wanted it to be a little more metaphorical. I had this idea of replacing the things we think of a robot being mechanical, with something more emotional. It’s not really saying that a robot is going to be made of plants, but the idea is that the whole robot is made of something more organic and softer rather than the classic 1950s tin toy robot idea. The concept came out of our associations of what we think of flowers and plants instead of hard metal and plastic.

How is illustrating science different from other fields like sports or politics?

In my visual language, science is one of the easiest things to illustrate. There are so many nouns involved. The great thing with science, even in something as abstract as arithmetic, is there’s always some sort of image involved in it, and lots of stuff—whether it’s robots or plant material—that’s exciting to draw. It’s funny, sometimes when I do a science piece, I don’t have to draw things accurately, but I do want to value the science and the research. In the past, I did pieces on the Internet and rogue waves, and I really did try to understand what the science was saying, so that my metaphor could add to it, but not undercut it. You don’t want to throw out the basic assumption or the concept of the piece. You can have fun with it but you always need to do it with some authority. You don’t want to take away from the authority of the writing and make it seem whimsical and sort of slapdash.

Do you leave the illustrations open to interpretations?

Yes. Most art that people respond to allows them to participate in it. If you give someone an image that says, “This is the way it is,” we don’t like those sort of solutions. We like things that ask something of us, that ask us to solve the story or figure it out in some way.

How should an illustration work with an article?

I think anytime you add illustrations, it should do something that strengthens the article. Hopefully it could challenge you to think of the content in a slightly different and metaphorical way, and the two should weave together and you should feel like, “I would love to read the article because I want to figure out what that image is about.”

Tomasz Walenta

Tomasz was born in Poland, grew up in Canada, and earned a master’s degree in graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, where he now lives. He has been a featured illustrator for Time, New Republic, and The Walrus, and has produced posters for cultural institutions in Europe and the United States. As the lead artist for our issue, “Fame,” Tomasz gave us evocative illustrations whose power was in big ideas with simple images. To accompany a story on how obsession with celebrity can be traced to our primate pasts, Tomasz transferred the famous descent of man chart onto a red carpet. His challenge for our article, “T.Rex Might be the Thing with Feathers,” was how to picture new research in paleontology showing that dinosaurs’ common ancestors are birds. Author Brian Switek argued that dinosaurs’ storied reputation as masters of all beasts was taking a hit from the knowledge, based on the discovery of a small dinosaur with feathers, Sinosauropteryx, that they evolved from birds. “Imagine the next Jurassic Park with an angry T. rex covered in feathers lunging at the tiny terrified humans,” Switek wrote. “How we see dinosaurs will keep changing for as long as we study them, and lesser-known species will undoubtedly be at the heart of whatever major transmutations to dinosaur imagery come next.”

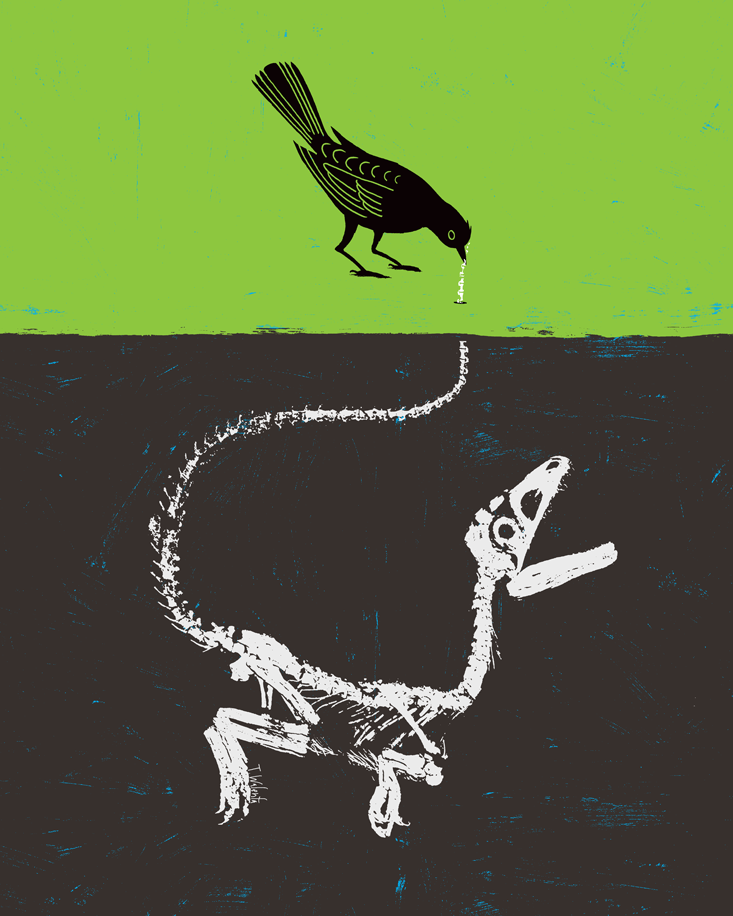

How did you settle on the image for “T.Rex Might be the Thing with Feathers”?

The idea behind the bird pulling the tail of the skeleton was a flash. I read the story about birds being an ancestor of dinosaurs and I was trying to find associations between dinosaurs and birds; it wasn’t easy, one is a skeleton, the other one is alive. I was searching for ideas, looking at images of birds, of skeletons, then at one point I saw an image of a chicken pulling a worm and that’s when I had the flash to associate the worm with the tail of the skeleton. The rest came naturally, the skeleton underground, the colors for the ground and grass and I changed the chicken to a “normal” bird. That’s how it happened.

How did you approach the theme of fame?

My approach consists of taking the main idea and translating it into a graphic language, using symbols, signs, or colors, and communicating the idea, not just the aesthetics. You have to understand what the article is saying and then use your imagination, experience, and knowledge of different symbolic elements to create an image. I always try to do minimalistic images because I want to show what’s necessary and that’s it.

What’s special about illustrating science?

Science has its own symbolic field. It has a lot of possibilities because you can use different elements, technical elements or skeletons—like in the dinosaur illustration—elements that have a symbolic meaning associated with a scientific concept. For me, a scientific assignment is very nice, because there are a lot of things I can choose from. When compared to a legal subject, say, there are very few elements—there are very few images that convey the idea of law. But in science the pool is very large, so it’s a lot more fun to work on a scientific project. You aren’t limited. I have to say the challenge in this particular assignment was the fame aspect, because fame is very abstract and hard to show.

How do you show science in an abstract or artistic way?

Usually, once you have the idea, you look for elements to convey it—and if there are not many elements, then look for a metaphor. That’s how I usually get away with it. It’s creating a metaphor that uses elements that aren’t literally related to the article but are related to this subject. The metaphor creates an image that tells a little story. If you try to show something like fame directly, it doesn’t succeed as an illustration because it becomes confusing. As for a metaphor, it has another power. When I look for ideas, I try to find as many as possible and one pops out. Then I have one thread that I pull and see where it takes me. It’s an experience and always a surprise, what comes at the end.

Do you leave room for viewers to make up their own minds?

Yes, that’s practically the most important thing. My style is very simple. I try not to impose anything on the reader. I try to give a basic concept and I present it to him as naked as possible, so he can dress it up with his own interpretation and imagination. I want the viewer be able to create a story of his own based on the suggestion that I have created.

What does an illustration add to an article?

I think it adds a certain vision and that’s the most important part, otherwise it just adds some color and life to text. My way of interpreting the story is my contribution to the story, the way my imagination works. I always try to summarize graphically what the idea of the story is. I hope that the reader has an idea of what he’s going to read, or if he doesn’t, he understands the idea behind the illustration. The impact of the illustration is either at the beginning or the end. It draws you in, or after you have read the story, you can say, “OK, I understand it now.”