Penn and Teller famously skewered the bottled water craze on their myth-busting Showtime series, Bullshit, setting up a hidden-camera sting operation in a fancy New York restaurant. A fake “water sommelier” stopped at each table, offering diners a special selection of high-end bottled water at $7 a pop. The catch: All the bottles were identical, filled with water from a garden hose out back. Seduced by flowery brand names like “L’eau du Robinet” (French for “tap water”), the diners waxed eloquent on the distinctive flavor profiles of the bottles they sampled, unaware they were being played.

Now, perhaps, the tables have turned with the recent debut of a sleek, 40-page water menu (pdf) at Ray’s and Stark Bar, a small upscale restaurant in the courtyard of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). It is the creation of German-born Martin Riese, a certified “water sommelier,” thanks to the German Mineral Water Trade Association. He is one of a mere 100 such professionals scattered around the world.

The very notion of a water sommelier elicits snickers and raised eyebrows in most quarters. Riese is accustomed to the eye-rolling and good-naturedly takes the skepticism in stride. Clearly he has latched onto a profitable trend. Water is a $12-billion-a-year industry, and Americans chugged 9.67 billion gallons of the stuff in 2012 alone—31 gallons per person. And since Riese introduced his special menu, water sales at Ray’s and Stark Bar have skyrocketed 500 percent.

Our party definitely had its share of skeptics when we sat down at our table and asked Riese to pick three bottles for a sampling. But we were open to learning otherwise, and Riese was happy to oblige. Slim and dapper in his impeccably tailored suit, with a broad welcoming smile, he is charming, earnest, and genuinely passionate about water. At least he didn’t need to convince me that water has a taste. I routinely bring a Sigg water bottle with me when I travel and fill it from taps and drinking fountains. I have definitely noticed a difference in taste in the tap water of different geographical regions.

That’s something Riese picked up on when he was just 4 years old, as he traveled throughout Europe with his parents. “Everyone said, ‘It’s all tap water,’ and none of it tasted the same to me,” he told Business Insider. “I couldn’t understand why everyone called it the same thing.”

Those subtle differences in flavor stem from the varying amounts of minerals in the water, or “total dissolved solids” (TDS) levels. This gives water from various sources a distinct “terroir,” much like wines, according to Riese. As he explained, all his offerings start out as rainwater, which falls on “different salts and layers of the ground,” absorbing the distinct mineral profile of that soil.

That’s why he turns up his nose at mass-produced bottled waters made from purified tap water, like Dasani and Aquafina, which all taste alike to him because of the purifying process. As for Los Angeles tap water, he told the Los Angeles Times that it tastes too much like chlorine for his liking: “I would never drink that water. When you have good food, good wine, and good spirits, you don’t want to contaminate that with this water.” If you’re going to drink tap water, Riese suggests you do so in Flensburg, Germany. And whatever you do, avoid distilled water, which has been stripped of all minerals entirely—a prospect he regards with horror. “Our bodies need minerals to be healthy!” (The FDA assures me that we can also get our minerals from food.)

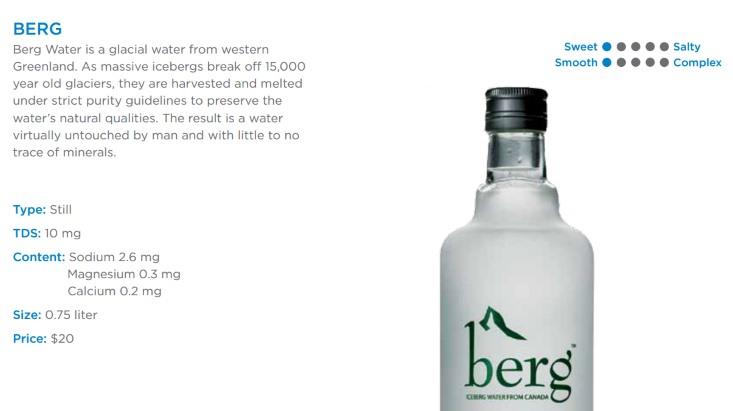

The water menu at Ray’s elevates water to the same level as wine, noting the geographical source for each bottle, whether it is still or sparkling, and carefully documenting the TDS ratings, including the specific concentrations of sodium, calcium, and magnesium. It also divides the flavor profiles into a four-pronged grid: sweet, smooth, salty, and complex.

First up was a bottle of Voss ($10), notable for its sleek cylindrical packaging, courtesy of a former chief design artist for Calvin Klein. Riese cautioned that at first it would taste just like any other bottled water—and it did—but it made for a nice baseline for the bottles to come. It has the lowest TDS rating of the three we sampled (just 22 milligrams) and falls into the “sweet and complex” category. Personally, I didn’t taste the complexity, but it was refreshing.

Next we sampled a bottle of Iskilde ($12)—“cold spring” in Danish—with a slightly higher TDS rating: 426 milligrams, mostly from calcium and sodium. This is supposedly “sweet and smooth.” Frankly, I couldn’t taste much difference from the Voss; the distinction is subtle, more one of texture than of taste. The Iskilde is silkier on the tongue. I confessed as much to Reise when he stopped by to check our progress, and he suggested sipping the water with my eyes closed. When we taste wine, he explained, we rely not just on taste but also on sight and smell. Water is odorless and colorless and hence lacks those additional cues, making it harder for the palate to pick up on subtle variations in the profile.

Technically Iskilde is a still water but it has a unique feature. “I am not Jesus, I cannot turn water into wine, but I can turn it into milk,” Riese quipped, then shook the bottle vigorously, forming tiny bubbles that turned the water cloudy, until the bubbles gradually dissipated. Why does a still water act like a sparkling water, even though it’s not carbonated? Extra oxygen! Chalk it up to a unique feature of the artesian spring in the Danish lake highlands from whence it came. According to Riese, as the water seeps up from the underground acquifer, it passes through layers of quartz sand and hard clay and also an air bubble filled with oxygen, which gives the resulting water a much higher oxygen content.

Finally we sampled a bottle of Vichy Catalan ($12), a “salty and complex” sparkling water from the Catalan region of Spain with a whopping TDS rating of 3,052 milligrams, a full third of which is sodium. This was hands-down the favorite at our table, even if our crude, untrained palates couldn’t distinguish the faint traces of potassium, bicarbonate, fluoride, and silica therein. We also inadvertently discovered what happens if you accidentally pour some Vichy Catalan into your glass of Voss. It alters the flavor profile ever so slightly to make it taste just like Pellegrino.

Alas, we didn’t get to taste the priciest item on the menu, a $20 Berg that was temporarily out of stock. It boasts the lowest TDS rating of all (10 milligrams), although its high value stems more from the fact that is harvested from remote icebergs in Greenland than its flavor. With almost no trace of minerals, it should be as flavorless as water is usually presumed to be. Nor did we sample the brand Riese designed, Beverly Hills 90H20 ($13). It has a similar TDS rating to the Iskilde (410 milligrams), with less sodium and calcium and more magnesium in the mix to make it ideal for pairing with food and wine.

Faced with all these very expensive bottles of water, a skeptical mind at some point wonders how much of the different flavors are due to actual differences in the chemistry of our watery selections, versus a kind of psychological effect? The human palate is easily fooled. Studies have shown that in blind taste tests, most people can’t tell the difference between tap and bottled water; participants either have no preference, or pick tap water over the bottled variety. Similar studies have been done with wine: Other blind taste tests have shown that people can’t tell the difference (pdf) between red wine and white wine, or between a fancy Grand Cru and cheaper vintages. Take two identical glasses of white wine and tint one with red food coloring and people will describe the former in the language favored for whites, and the latter with language typically used with reds, even though both are the same white wine. As Penn and Teller made crystal clear, we are heavily influenced by packaging, by pricing, by brand name, and other psychological factors.

We drink what we think—quite literally. In fact, when subjects in a 2008 brain-scanning study sipped wine they were told was expensive, they reported enjoying it more. Their brain activity supported that perception, registering stronger activity in the region most associated with pleasure (medial orbitofrontal cortex) when participants thought they were drinking a $90 Cabernet than when they thought they were drinking a $10 wine.

Given all that, the folks at Priceonomics conclude, “If wine is bullshit, then isn’t everything else we eat and drink bullshit too?” Isn’t everything we perceive filtered by our experiences, our expectations, our state of mind? The same might be said of the water menu at Ray’s. Perhaps that’s why Riese chose to quote Wallace Stevens in its pages: “Human nature is like water. It takes the shape of its container.” I think it’s just a little too glib to summarily dismiss Riese’s chosen profession as mere smoke and mirrors. Maybe we’re co-conspirators rather than clueless marks. Think of it this way: You’re not just paying for bottled water; you’re buying into the full sensory experience, including Riese’s colorful shtick. The pretension is part of the packaging.

So go ahead. Indulge a little. I highly recommend the Iskilde.

Jennifer Ouellette is a science writer and the author of The Calculus Diaries and Me, Myself and Why: Searching for the Science of Self. Follow her on Twitter @JenLucPiquant.