Coral reefs, already among the most endangered ecosystems on Earth, face a deadly new threat—one that most divers and scientists have missed. Harmful algal crusts known as PACs have apparently been spreading undetected across shallow tropical reefs for decades.

“Everywhere that we see a PAC, corals cannot get a footing,” says Bryan Wilson, a coral biologist from the University of Oxford and co-author of a new paper that details the damage PACs can do to reefs—and the surprising extent of the killers’ range.

These PACs, or peyssonnelid algal crusts, now cloak large swaths of reef throughout the Caribbean and Indo-Pacific. In St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands, for example, they cover up to 64 percent of the seafloor in shallow waters. Though the study site in St. John has been surveyed for 35 years now, PACs only caught the eye of Wilson’s colleague and co-author Peter Edmunds a decade ago. The algae were missed because they are difficult to accurately identify and are often misclassified. PACs were simply not on diver survey lists and were easy to ignore.

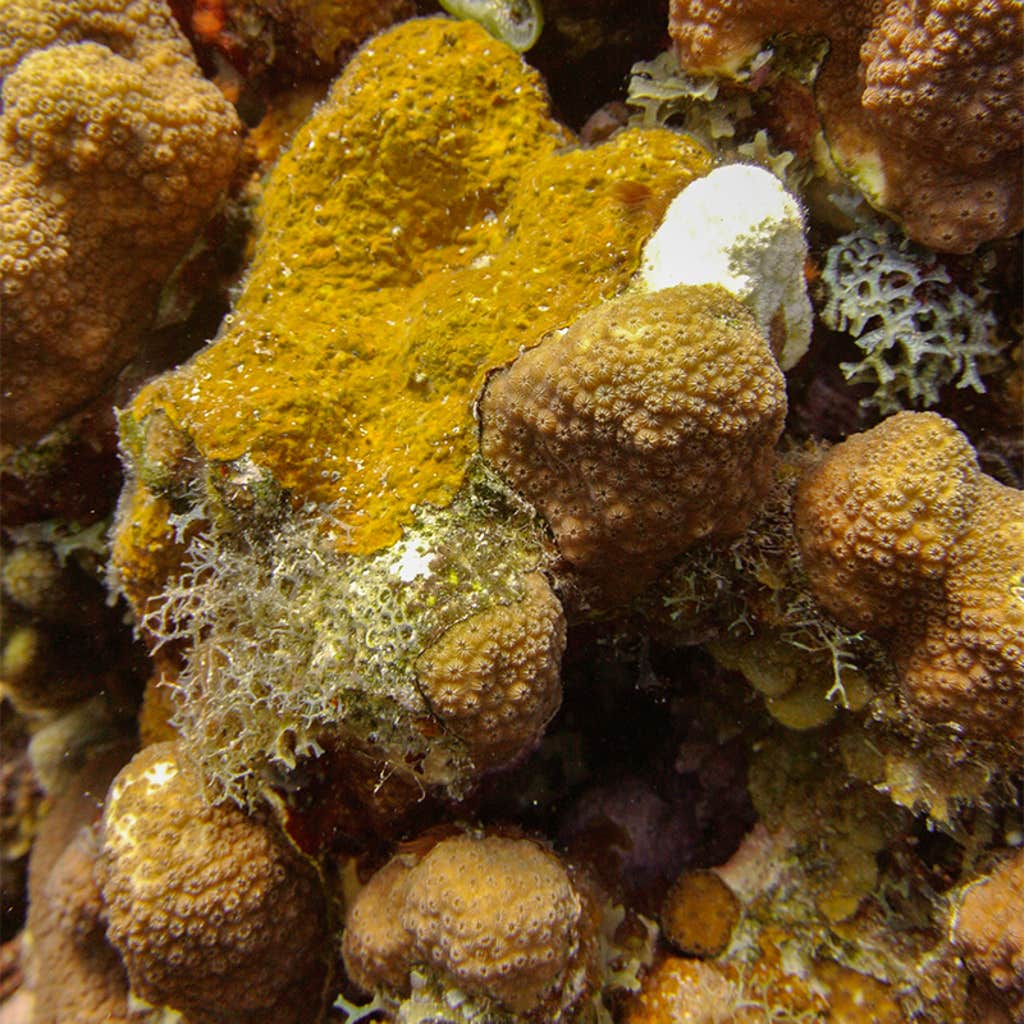

Photo by Peter Edmunds.

To a trained diver surveying a reef, a PAC may look like a brittle carpet with wart-like protrusions. These algal crusts come in a variety of shades—from golden to red to black—but they can easily be mistaken for other kinds of algae, and with a dusting of sand, they may be confused for a non-living component of the seascape. Tom Schils from the University of Guam, also a co-author on the paper, says even the designation “PAC” is new, grouping together a large number of crust-forming species of red algae from the order Peyssonneliales.

“Some PAC species have a broad range and can behave in a similar fashion ecologically in very distinct parts of the world,” Schils explains. They are also far more common than scientists realized.

Following a destructive event like a hurricane, PACs thrive, quickly spreading into a thick coating along the seafloor, which then actively deters coral larvae from landing and starting a new colony. PACs also disturb algae and bacterial species that help healthy coral larvae find desirable spots to settle, as well as get the nutrients they need and guard against disease. Where to settle is an important decision, since corals can, under the right conditions, live in their watery neighborhoods for centuries. The working hypothesis is that PACs produce antibiotics that target and kill off certain species of the corals’ symbiotic bacteria, which is akin to “switching off the landing lights on a runway,” Wilson says.

Algal crusts now cloak large swaths of reef throughout the Caribbean.

Climate change is making the tropical oceans more and more hospitable to PACs, as they tolerate warmer temperatures and higher acidities. They also have few natural reef predators because their hard, crusty texture makes them difficult for most grazers to consume. “It took me an hour to chip off a thumbnail [of PAC] from a reef using a hammer and a gavel,” Wilson recalls. The only known PAC grazer is the long-spined sea urchin Diadema antillarum, which is also rapidly declining in tropical seas.

Wilson and Schils want to develop molecular diagnostic tools for quickly identifying PACs that don’t rely on their varied appearance. In the meantime, though, they are desperate to get the word out about PACs to coral biologists around the world—so they will know what to look for. Wilson says, “I hate to say it, but PACs look like a real winner for the warmer and more acidic waters of the future world.” ![]()

Lead photo: A large patch of PAC growing among sea fans at about 3 meters’ depth in St. John, taken November, 2023. Credit: Peter Edmunds.