The eyes are the window to the soul, as the old adage goes—but they also, apparently, can help us spot a fake.

According to new research, analyzing reflections in a person’s eyes with tools used by astronomers to survey the cosmos can accurately determine whether a photo is AI-generated about 70 percent of the time.

Kevin Pimbblet, director of the Centre of Excellence for Data Science, Artificial Intelligence, and Modelling at the University of Hull, United Kingdom, who oversaw the new work, says he became interested in applying new methods to the problem of deepfakes when he started creating AI-generated images himself. He began to notice that the eyes in the pictures didn’t obey the laws of physics—there were subtle differences between the reflections in the left and right eyes. It made him want to look deeper.

It’s very much an arms race.

Deepfake photos can be used to spread misinformation—and pose a threat to privacy and security. It’s a particularly salient problem in a year of elections around the world, including the United States, United Kingdom, and India. Some researchers call AI-generated content the biggest new threat to elections in 2024.

For the study, Pimbblet and his student, Adejumoke Owolabi, created a series of fake images themselves and collected real ones from an online dataset of 70,000 faces called the Flickr-Faces-HQ Dataset. Then they analyzed these images using two tools often employed in astronomy research: the Gini Index and the CAS system. Their findings, which served as the basis for Owolabi’s master’s thesis, were presented at the U.K. Royal Astronomical Society’s National Astronomy Meeting in July. (The research hasn’t been published yet, but Pimbblet is working to submit it to journals.)

The Gini index, created in 1912 by an Italian statistician, is a way to measure the inequality in a set of data. Astronomers use it to assess the distribution of light in photographs of galaxies. An analysis of the photograph’s pixels can tell them if the light is evenly distributed or concentrated in places, which would suggest chunks of stars. CAS—which stands for concentration, asymmetry and smoothness—can similarly be used to measure the distribution of light in a galaxy or other object.

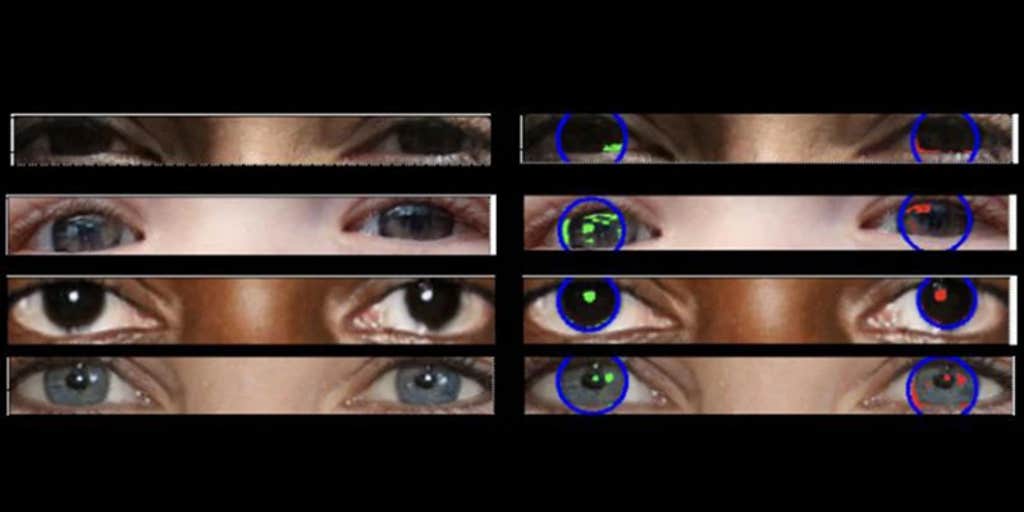

With the two tools, Pimbblet and Owolabi analyzed the reflections in the eyes of people in their photographs. They found that Gini worked better than CAS at finding fakes. If the reflections were the same size and shape in both eyes, the photo was probably real—and if not, it was probably a fake.

“It’s not foolproof,” says Pimbblet of the new method. “It’s merely another way in which you can add to a string of arguments to say it might be fake.”

Pimbblet admits that publishing the results will likely encourage deepfake creators to simply adjust their algorithms to create more accurate eyes in the photos. “It’s very much an arms race,” he says, “where the people who are generating the fakes get better at it, and the people who are trying to tell the difference get better at their game as well.”

Pimbblet plans to use CAS and the Gini Index to analyze larger datasets. He says that similar methods could be used to determine fakes from variations in skin tone.

Tommaso Treu, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Los Angeles, says it’s exciting to see astrophysics tools applied outside of the discipline. The new research is “a very interesting idea,” he says. “Astrophysicists have invested a lot of brainpower in analyzing images so their tools should have very broad applications.”

History is full of examples in which the tools of one discipline enabled breakthroughs in a different discipline, such as neural networks that can be applied to everything from character recognition to astronomy. He also points out that the Gini index—which measures inequality—was originally designed for use in economics, and only later applied to astronomy.

“We’re transferring technology across from one area of endeavor to another,” says Pimbblet, “and that’s really where the forefront of a lot of research lies.” ![]()

Lead image: Kitreel / Shutterstock