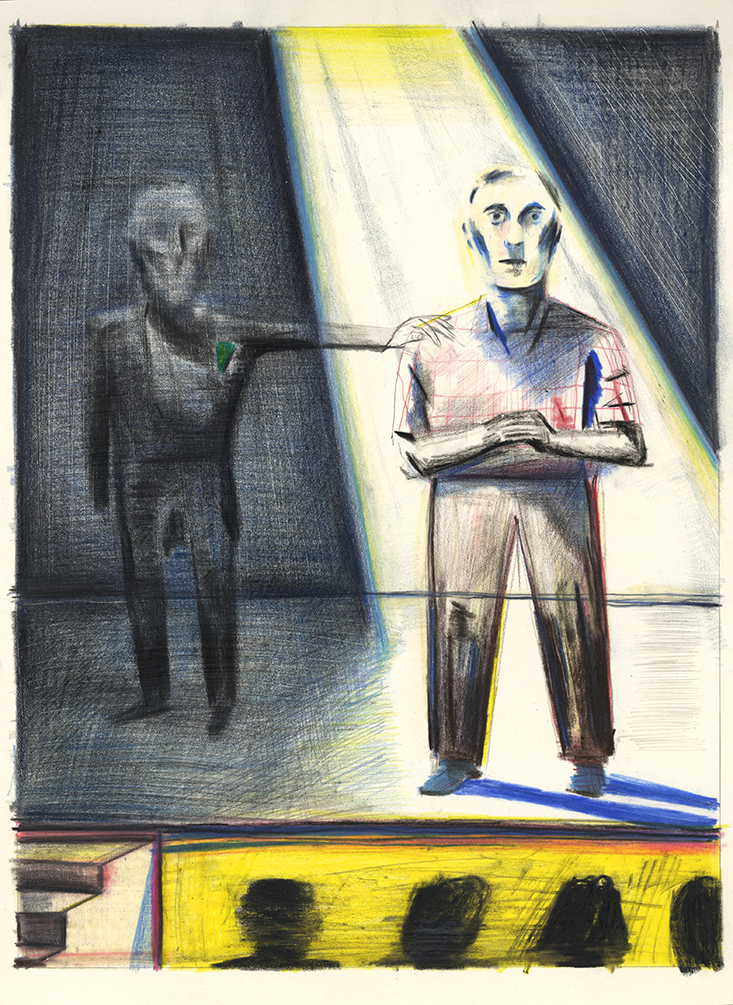

The light dimmed and the murmur of conversation died away. The curtain opened. Lindemann was standing on the stage.

He was plump and had a bald spot made all the more noticeable by the few sparse hairs combed over the nakedness of his skull, and he was wearing black horn-rim spectacles. His suit was gray, and there was a little green handkerchief in the breast pocket. Without preamble, without so much as a bow, he softly began to speak.

Hypnosis, he said, was not the same as sleep, but rather a state of inner wakefulness, not submission, but self-empowerment. The audience would witness astonishing things today, but nobody need have cause for concern, for nobody could knowingly be hypnotized against their will, and nobody could be made to perform some act that in the depths of their soul they were not ready to perform. He then paused for a moment, and smiled as if he’d just delivered some rather abstruse joke.

A narrow set of steps led down from the stage into the audience. Lindemann descended them, touched his glasses, looked around, and walked up the center aisle. Obviously he was now deciding which people to take back up onto the stage. Ivan, Eric, and Martin lowered their heads.

“Don’t worry,” said Arthur. “He only takes grownups.”

“So maybe it’ll be you.”

“It doesn’t work on me.”

A little man was clenching his jaws, the hands of a lady with hair pulled into a bun were shaking, as if she wanted to tear free.

They were about to see something big, said Lindemann. Anyone who didn’t want to participate mustn’t worry, he wouldn’t come too close, the person would be excused. He reached the last row, ran back surprisingly nimbly, and jumped up onto the stage. For starters, he said, something light, just a joke, a little something. Everyone in the first row, please come up here!

A murmur ran through the theater.

Yes, said Lindemann, the first row. All of you. Please be quick!

“What does he do if someone says No,” whispered Martin. “If someone just stays in his seat, then what?”

Everyone in the first row stood up. They whispered to one another and looked around unwillingly, but they obeyed and climbed up onto the stage.

“Stand in a line,” Lindemann ordered. “And hold hands.”

Hesitantly, they did so.

No one was to let go of anyone else, said Lindemann as he walked along the line, no one would want to so no one would do it, and because no one would want to, no one would be able to, and because no one would be able to, it wouldn’t be wrong to declare that everyone was literally sticking to one another. As he was talking, he reached out here and there to touch people’s hands. Tight, he said, hold hands tight, really tight, nobody step out of the line, nobody let go, really tight, indissoluble. Anyone who wanted to should try and see what happened now.

Nobody let go. Lindemann turned to the audience, and there was some timid applause. Ivan leaned forward to get a better look at the people on stage. They looked uncertain, absentminded, somehow frozen. A little man was clenching his jaws, the hands of a lady with hair pulled into a bun were shaking, as if she wanted to tear free, but was finding that her neighbor’s grip, just like her own, was too strong.

He would count to three, said Lindemann, then everyone’s hands would let go. “So one. And two. And…,” he slowly lifted his hand. “Three!” and snapped his fingers.

Uncertainly, almost unwillingly, they let go, looking at their hands in embarrassment.

“Now go sit down again quick” said Lindemann. “Down. Quick. Quick.” He clapped his hands.

The woman with the bun was pale, and swayed as she walked. Lindemann took her gently by the elbow, led her to the steps, and spoke to her quietly. When he let go, she was more sure-footed, went down the steps, and reached her seat.

That had been a little experiment, said Lindemann, an opening trick. Now for something serious. He went to the front of the stage, took off his glasses, and squinted with his eyes scrunched up. “The gentleman in front over there in the pullover and the gentleman right behind him, and you, young lady, please come up.”

Smiling awkwardly, the trio climbed onto the stage. The woman waved at someone, Lindemann shook his head in reproof, and she stopped. He positioned himself next to the first of them, a tall, heavyset man with a beard, and held his hand in front of the man’s eyes. He spoke into his ear for a while, then suddenly called, “Sleep!” The man fell over, Lindemann caught him and laid him down on the floor. Then he stepped over to the woman next to him and the same thing happened. And then again with the other man. They all lay there motionless.

“And now be happy!”

He must explain, he said. Lindemann turned toward the audience, removed his horn-rims, pulled the green handkerchief out of his breast pocket, and began to polish them. They were all only too familiar, were they not, with the stupid suggestions that mediocre hypnotists—pretentious and untalented incompetents of the sort you encounter by the dozen in any profession—love to instill in their guinea pigs: freezing cold or boiling heat, bodily stiffness, sensations of flying or falling, not to mention the universally beloved forgetting of your own name. He paused and stared thoughtfully into the air. It was hot in here, wasn’t it? Terribly hot. So what could be going on? He mopped his brow. Such idiocies were familiar to everyone and he would skip them without further ado. My God, wasn’t it hot!

Ivan pushed his wet hair back off his forehead. The heat seemed to be rising off the floor in waves, the air was damp. Eric’s face was all shiny too. Programs were flapping the air all over the audience.

But something could surely be done to fix it, said Lindemann. Not to worry, the theater had capable technicians. Someone would turn on the excellent air-conditioning at any moment. In fact, it had already been done. Up here you could already hear the humming of the machinery. You could feel the rush of air. He turned up his collar. But now it really was blowing terribly. The equipment was astonishingly powerful. He blew on his hands and shifted from foot to foot. It was cold in here, very cold, really very, very cold indeed.

“What’s going on?” said Arthur.

“Haven’t you noticed?” whispered Ivan. His breath was rising in clouds, his feet had turned numb, and he was having trouble inhaling. Martin’s teeth were chattering. Eric sneezed.

“No,” said Arthur.

“Nothing?”

“I told you, it doesn’t work on me.”

Life could seem immense and miraculous now, but the truth was nothing lasted, everything rotted away, everything died.

But that was not enough, said Lindemann. Over. The end. As he’d already said, he didn’t want to waste anyone’s time with such tricks. Now he was going to get to something interesting without any further delay, namely, the direct manipulation of the powers of the mind. The lady and the gentleman here on the floor had already been following his instructions for some time. They were happy. Right here and now, in full view of everyone, they were experiencing the happiest moments of their lives. “Sit up!”

Awkwardly, they hauled themselves up into a sitting position.

“Now look,” said Lindemann to the woman in the middle.

She opened her eyes. Her bosom rose and fell. There was something unusual about the way she was breathing and the way her eyes moved. Ivan didn’t really understand it, but he recognized something large and complex. He noticed a woman in the row in front of him turning her eyes away from the stage. The man next to her shook his head indignantly.

“Eyes closed,” said Lindemann.

The eyes of the woman on the stage closed immediately. Her mouth was open, a thin stream of saliva was running out of it, and her cheeks shone in the spotlights.

Alas, said Lindemann, nothing lasted forever, and the best things always ended first. Life could seem immense and miraculous now, but the truth was that nothing lasted, everything rotted away, everything died, without exception. One almost always repressed that fact. But not now, no, not at this particular moment. “Now you know it.”

The bearded man groaned. The woman slowly sank backwards and held her hands over her eyes. The other man sobbed quietly.

But, said Lindemann, one could still feel cheerful. Life being a short day between two endlessly long nights, one should enjoy the bright moments even more and dance for as long as the sun still shone. He clapped his hands.

Obediently this trio stood up. Lindemann clapped the beat, slowly at first, then faster. They leapt like marionettes, throwing their limbs this way and that, and spun their heads. There was absolute silence, no one coughed, no one cleared their throat, the audience seemed transfixed by horror. The only sound was the stamping and panting coming from the stage, and the creaking of the boards.

“Now lie down again,” said Lindemann. “And dream!”

Two of them immediately sank to the floor, while the man furthest to the left still remained standing, and seemed to grope with his hands—but then his knees also buckled, and he stopped moving. Lindemann bent down and looked at him closely. Then he turned to face the audience.

He said he now wanted to conduct a difficult experiment. Only a handful of practitioners could pull it off, it required the highest skills. “Dream deeply. Deeply, deeper than ever. Dream a new life. Be children, learn, grow up, fight, suffer, and hope, win and lose, love and lose again, grow old, grow weak, grow frail, and then die, it all goes so fast, and when I tell you, open your eyes and none of it will have happened.”

He folded his hands and stood there silent for a long moment.

This experiment, he finally said, didn’t always work. Certain subjects woke up and had experienced nothing. Others, by contrast, had begged him to erase their memories of the dream because the experience was too disturbing, in order to regain the ability to trust both time and reality. He checked the time. But meantime, in order to occupy themselves while they were waiting, a couple of simple things perhaps? Any children in the audience? He went up on tiptoe. That boy there in the fifth row, the little girl on the end, and this boy in the third row, the one who’s the spitting image of the boy right next to him. Come up!

Ivan looked to the right, then the left, and behind him. Then he pointed to himself questioningly.

“Yes,” said Lindemann. “You.”

“But you said he only calls grownups onto the stage,” whispered Ivan.

“Well, I was wrong.”

Ivan felt the blood rush into his face. His heart pounded. The other two children were already on their way to the stage. Lindemann fixed him with his eyes.

“Just stay where you are,” said Arthur. “He can’t order you around.”

Ivan slowly got to his feet. He looked around. Everyone was looking at him, everyone in the auditorium, every single person in the entire theater. No, Arthur was wrong, there was no way to refuse, it was, after all, a hypno-show, and whoever had come had to take part. He heard Arthur say something else, but didn’t understand it, his heart was thumping too loudly, and he was already starting toward the stage. He pushed past the knees of the people in the seats and went up the center aisle.

How bright it was up here. The spotlights were unexpectedly powerful and the people in the audience mere outlines. The three grownups were lying motionless, no sign of life, no sign of breath. Ivan looked out into the orchestra but couldn’t locate Arthur or his brothers. Lindemann was already right there in front of him, down on one knee, pushing him back a step very carefully, as if he were a fragile piece of furniture, and looking into his face.

“We’re going to do it,” he said softly.

Up close, Lindemann looked older. There were furrows around his mouth and eyes, and his makeup was sloppy. Anyone painting his portrait would have had to concentrate on the eyes, deep-set and hooded behind the horn-rims: restless, unreadable eyes, giving the lie to the cliché that hypnotists stared so intensely that a subject would lose himself in their gaze. Besides which, he smelled of peppermint.

“What’s your name?” he asked in a slightly louder voice.

Ivan swallowed and told him.

“Relax, Ivan,” said Lindemann, his voice now loud enough to carry to the people in the front few rows. “Fold your hands, Ivan. Clasp your fingers.”

Ivan did so, wondering how anyone was supposed to relax on a stage in front of so many people. Lindemann couldn’t mean it seriously; he was just saying it to confuse him.

“That’s right.” Lindemann was now addressing all three children, loud enough to be heard anywhere in the theater. “Absolutely quiet, absolutely relaxed, but you can no longer separate your hands. They’re stuck to each other, you can’t do it.”

But it wasn’t true! Ivan could easily have separated his hands, he felt no resistance and no blockage. But he didn’t feel like blaming Lindemann. He just wanted it to be over.

Lindemann talked and talked. The word relax kept being repeated, and he kept saying something about listening and obeying. Maybe it was working with the other two, but it was having no effect on Ivan. He felt no different than before, there was absolutely no question of a trance. It was just that his nose itched. And he needed to go to the toilet.

“Try,” said Lindemann to the boy next to Ivan. “You can’t let go, you can’t, try, you won’t be able to.”

Ivan heard a deep rumbling noise; it took him a few moments to realize that it was laughter. The audience was laughing at them. But not at me, thought Ivan, he must have noticed it’s not working on me, that’s why he’s not giving me questions.

“Lift your right foot,” said Lindemann. “All three of you. Now.”

Ivan saw the other two lift their feet. He could feel all eyes on him. He was sweating. So what could he do? He lifted his foot. Now they’d all think he was hypnotized.

“Forget your name,” said Lindemann to him.

He could feel the anger rising in him. It was all becoming truly stupid. If the man asked him again, he’d show him up in front of everyone.

“Say it!”

Ivan cleared his throat.

“You can’t, you’ve forgotten it, you can’t. What’s your name?”

The problem was the situation, it was so horribly bright and also really hard to stand on one leg in front of all those people, it took all your concentration to keep your balance. It wasn’t his memory that was letting him down, it was his voice. It stuck in his throat and wouldn’t come out. Whatever anyone asked him now, he’d have to stay silent.

“How old are you?”

“Thirteen,” he heard himself say. So by sheer will he could do it.

“What’s your mother’s name?”

“Katharine.”

“Your father?”

“Arthur.”

“Is that the gentleman down there?”

“Yes.”

“And what’s your name?”

He said nothing.

“You don’t know it?”

Of course he knew it. He could feel the shape of its contours; he knew where it was in his memory; he felt it, but it seemed to him that the person this name belonged to was not the person Lindemann was asking, so none of all this really hung together, and was completely irrelevant when set against the fact that he was on one leg on a stage with an itchy nose, his hands squeezed together, and he needed to go to the toilet. And then the name came back to him again, Ivan of course, Ivan, he drew and opened his mouth ...

“And you?” Lindemann asked the boy next to him, “do you know your name?”

Now I’ve got it, Ivan wanted to shout, now I can say it! But he stayed silent, it was a relief that the whole thing was no longer about him. He heard Lindemann ask the other two something, he heard them answer, he heard the audience laugh and clap. He felt drops of sweat running down his forehead, but he couldn’t wipe them away, it would have been embarrassing to move his hands now when they all thought he was in a trance.

Wild applause erupted, with stamping of feet and calling, as if nothing were more important to everyone than getting Lindemann’s wish granted.

“It’s already over,” said Lindemann. “Not so bad, was it? Separate your hands, stand on both legs, you know your names again. It’s over. Wake up. It’s over.”

Ivan lowered his foot. Of course it was easy, he could have done it the whole time.

“It’s okay,” said Lindemann softly, putting a hand on his shoulder. “It’s over.”

Ivan went down the steps behind the other two. He would have liked to ask them what it had been like for them, what they’d seen and thought, how it felt to be genuinely hypnotized. But he was already back in the third row, people made room for him, he pushed past their knees, and dropped into his seat. He let out a breath.

“How was it?” whispered Martin.

Ivan shrugged.

“Do you remember, or have you forgotten it all?”

Ivan wanted to answer that of course he hadn’t forgotten anything and that the whole thing had been a silly trick, but then he realized that the people in the rows in front of them had turned round. They weren’t looking at the stage, they were looking at him. He glanced around. The whole theater was looking at him. Lindemann had lied. It wasn’t over.

“Is that him?” asked Lindemann.

Ivan stared up at the stage.

“Your father. Is that him?”

Ivan looked at Arthur, looked at Lindemann, looked back at Arthur. Then he nodded.

“Would you like to join me, Arthur?”

Arthur shook his head.

“You think you don’t want to. But you do. Believe me.”

Arthur laughed.

“It doesn’t hurt, it isn’t dangerous, you might even like it. Give us the pleasure.”

Arthur shook his head.

“Not at all curious?”

“It doesn’t work on me,” called Arthur.

“Perhaps not. Maybe that’s right, it can happen. All the more reason for you to come up here.”

“Take someone else.”

“But I want you.”

“Why?”

“Because that’s what I want. Because you believe you don’t want to.”

Arthur shook his head.

“Come!”

“Go on,” whispered Eric.

“They’re all looking at us,” whispered Ivan.

“So what?” said Arthur. “Let them look. Why do children find everything embarrassing?”

“Let’s all say it together!” called Lindemann. “Send him up here to me, show him, clap if you think he should come. Clap loud!”

Wild applause erupted, with stamping of feet and calling, as if nothing were more important to everyone than getting Lindemann’s wish granted, as if none of them could imagine anything more satisfying than seeing Arthur up on stage. The noise achieved a crescendo as more and more voices joined in: People were clapping and yelling. Arthur didn’t budge.

“Please!” cried Eric.

“Please go,” said Martin. “Please!”

“Only for you,” said Arthur and got to his feet. He worked his way through the howling crowd to the center aisle, walked to the steps, and climbed them. Lindemann made a rapid gesture and the racket ceased.

“You’re going to have bad luck with me,” said Arthur.

“Possibly.”

“It really doesn’t work.”

“That nice boy. That was your son?”

“I’m sorry. I’m the wrong person. You want someone who feels awkward first of all, and then chats with you and tells you things about himself, so that you can turn him into a joke and make everyone laugh. Why don’t we skip all that? You can’t hypnotize me. I know how it works. A little pressure, a little curiosity, the need to belong, the fear of doing something wrong. But not with me.”

Lindemann said nothing. The lenses of his glasses glinted under the spotlights.

“Can they hear us?” Arthur pointed to the three motionless bodies.

“They’re busy with other things.”

“And that’s what you’d like to do with me too? Give me another life?”

Ivan wondered how his father was managing to let them all understand every word he said. He had no microphone and he was speaking softly, yet he was completely audible. He stood there calmly as if he were alone with the hypnotist and allowed to ask whatever he wanted. Nor did he seem to be absent-minded any more. He seemed to be enjoying himself.

Lindemann, on the contrary, looked unsure of himself for the first time. He was still smiling, but frown lines had appeared on his forehead. Gingerly he took off his glasses, put them on again, took them off once more, folded them up, and pushed them into his breast pocket behind the green handkerchief. He raised his right hand and held it over Arthur’s forehead.

“Look at my hand.”

Arthur smiled.

The sound of giggling spread through the audience. Lindemann grimaced for a moment. “Look at my hand, look at it, look at my hand. Just my hand, nothing else, just at my hand.”

“I don’t notice anything.”

“Nor should you.” Lindemann sounded agitated “Just look! Look at my hand, my hand, nothing else.”

“You’re focusing my consciousness on itself, aren’t you? That’s the trick. My attention is focused on my own attention. A slipknot, and suddenly, it’s impossible ...”

“Are those your sons down there?”

“Yes.”

“What are their names?”

“Ivan, Eric, and Martin.”

“Ivan and Eric?”

“The Knights of the Round Table.”

“Tell us about yourself.”

Arthur said nothing.

“Tell us about yourself,” Lindemann said again. “We’re all friends here.”

“There’s not much to say.”

“What a pity. How sad, if true.”

Lindemann lowered his hand, bent forward, and looked at Arthur in the face. Everything was very quiet, the only sound was a faint hiss, perhaps from the air conditioning, perhaps from the electrical current to the spotlights. Lindemann took a step back, a board creaked, one of the sleeping bodies groaned.

“What do you do for a living?”

Arthur said nothing.

“Or don’t you have a job?”

“I write.”

“Books?”

“If what I write got printed, they’d be books.”

“Rejections?”

“A few.”

“That’s bad.”

“No, it doesn’t matter.”

“It doesn’t bother you at all?”

“I’m not that ambitious.”

“Really?”

Arthur said nothing.

“You don’t look as if you’d settle for a little. You might want to believe that of yourself, but actually you don’t. What do you really want? We’re all friends here. What do you want?”

“To get away.”

“From here?”

“From everywhere.”

“From home?”

“From everywhere.”

“It doesn’t sound as if you’re happy.”

“Who’s happy?”

“Please answer.”

“No.”

“Not happy?”

“No.”

“Say that again.”

“I’m not happy.”

“Why do you stick it out?”

“What else is there to do?”

“Run?”

“You can’t just keep running.”

“Why not?”

Arthur didn’t reply.

“And your children? Do you love them?”

“You have to.”

“Right. You have to. All of them equally?”

“Ivan more.”

“Why?”

“He’s more like me.”

“And your wife? We’re all friends here.”

“She likes me.”

“That wasn’t the question.”

“She earns money for us, she takes care of everything, where would I be without her?”

“Free perhaps?”

Arthur said nothing.

“What do you think of me? You didn’t want to come up to the stage, and now you’re standing here. You thought it wouldn’t work on you. What do you think now? For example, of me?”

“A little man. Insecure about everything, which is why you are what you are. Because without all this here, you’d be nothing. Because you stutter whenever you’re not up here.”

Lindemann was silent for some moments, as if giving the audience the chance to laugh, but there wasn’t a sound. His face looked white and waxy; Arthur stood very straight, his arms by his sides, stock-still.

“And your work? Your writing? Arthur, what is it with all that?”

“Not important.”

“Why not?”

“A hobby. No reason to fuss about it.”

“It doesn’t bother you that your work doesn’t get published.”

“No.”

“That you aren’t any good? It doesn’t bother you?”

Arthur took a small step back.

“You think you have no ambition? But maybe it would be better if you did, Arthur. Maybe ambition would be an improvement, maybe you should be good, maybe you should admit to yourself that you want to be good, maybe you should make the effort, maybe you should work at it, maybe you should change your life. Change everything. Change everything, Arthur. What do you think?”

Arthur said nothing.

Lindemann moved even closer to him, went up on tiptoe and put his face close to Arthur’s. “This superiority. Why make the effort, is what you’ve always thought, isn’t it? But now? Now that your youth is over, now that everything you do carries weight, now that there’s no time to be casual anymore, what now? Life is over very quickly, Arthur. And it gets squandered even quicker. What needs to happen? Where do you want to go?”

“Away.”

“From here?”

“From everywhere.”

“Then listen to me.” Lindemann put a hand on Arthur’s shoulder. “This is an order, and you’re going to follow it because you want to follow it, and you want to because I’m ordering you, and I’m ordering you because you want me to give the order. Starting today, you’re going to make an effort. No matter what it costs. Repeat!”

“No matter what it costs.”

“Starting today.”

“Starting today,” said Arthur. “No matter what it costs.”

“With everything you’ve got.”

“No matter what it costs.”

“And what just happened here shouldn’t bother you. You can think back on it quite cheerfully. Repeat.”

“Cheerfully.”

“And it really isn’t important. It’s all a game, Arthur, just fun. A way to pass the time on an afternoon. Just like your writing. Like everything people do. I’m going to clap my hands three times, then you can go and sit down.”

Lindemann clapped his hands: once, twice, three times. There was no sign of any change in Arthur. He stood just as he had before, back straight, his neck tilted slightly backward. There wasn’t a sound to be heard. Hesitantly, he turned around and went down the steps. Gradually timid applause broke out here and there, but once Arthur had reached his seat, it crescendoed into a thunder. Lindemann bowed and pointed to Arthur. Arthur imitated him with an empty smile and bowed back.

That was what was so wonderful about his métier, said Lindemann when the noise had finally died down. One never knew what the day would bring, one could never foresee the demands that would be made on one. But now finally for the high point, the star turn. With a light touch on her cheek he wakened the sleeping woman and asked what she had experienced.

She sat up, but after a few sentences the excitement took her breath away. She panted, sobbed, gasped for air. In tears, she described a life as a farmer’s wife in the Caucasus, and a hard childhood in the winter cold, she spoke about her brothers and sisters, her father and mother, her husband, the animals, and the snow.

“Can we go?” whispered Ivan.

“Yes, please,” said Eric.

“Why?”

“Please,” said Martin. “Please, let’s go! Please.”

As they stood up, there was the sound of snickering in the audience. Eric clenched his fists and said to himself that he was only imagining it all, while Martin understood for the very first time that people could be mean-minded and spiteful, taking malicious pleasure in things for no reason at all. They could also be spontaneously good, friendly and supportive, and both these qualities could exist simultaneously in the same person. But above all, people were dangerous. This realization would stay with him permanently, bound up forever with a memory of Lindemann’s face looking down from the stage at their departure, as he polished his glasses with the green handkerchief. At the very moment Martin, bringing up the rear, was leaving the theater, he caught Lindemann’s expression: eyebrows arched, smiling, wet tongue peeping from a corner of his mouth. Then there was a little click and the door closed behind him.

The whole way home, Arthur beat time on the steering wheel and whistled. Martin sat very straight next to him, while Ivan stared out of one window and Eric out of the other. Twice Arthur asked what on earth had upset them, why they’d wanted to leave, and why in the world children found everything so embarrassing, but when no one replied, he just said there were some things he’d never understand. That woman, he cried, that idiotic story about the Russian farm, all laid on far too thick, obviously she worked in cahoots with the hypnotist, childishly easy to see through, who would believe stuff like that! He turned on the radio, then turned it off again, then on again, and then, not very long afterward, off again.

“Did you know,” he asked, “that the condor flies higher than any other birds?”

“No,” said Eric. “I didn’t know.”

“So high that sometimes it’s no longer visible from the ground. As high as a plane. Sometimes so high, that the distance above it is shorter than the distance below.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” asked Ivan. “Above it to where?”

“You know, above it!” Arthur rubbed his forehead. For a few seconds he steered with his eyes closed.

“I don’t understand,” said Martin.

“What’s there to understand? I’d rather you tell me about school and how it’s going, you never say anything.”

“Everything’s fine,” said Martin quietly.

“No problems, no difficulties?”

“No.”

The car stopped by the house long enough to release the boys while Arthur remembered he had to run an errand. It wasn’t till a telegram arrived shortly after midnight that their mother got them out of bed and made them tell her all about it. Arthur had taken his passport and all the money in their joint account. There were only two sentences in the telegram: First, he was fine, no need for concern. Second, not to wait for him. He wouldn’t be coming back for a long time.

Daniel Kehlmann is the recipient of numerous prizes, including the Candide Prize, the Literary Prize of the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, the Doderer Prize, the Kliest Prize, the Welt Literature Prize, and the Thomas Mann Prize. His novel Measuring the World was translated from German into more than 40 languages.

Excerpt From the Book: F by Daniel Kehlmann, translated by Carol Brown Janeway.

Originally published in German under the title F.

Copyright © 2013 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Reinbek bei Hamburg.

English translation copyright © 2014 by Carol Brown Janeway.

Published by arrangement with Pantheon Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC. U.K. edition is published by Quercus in October 2014.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2014 Nautilus Quarterly.