In May of 1924, the city of Chicago was shocked by a brutal murder. Two precocious University of Chicago graduate students, Nathan Leopold, 19, and Richard Loeb, 18,1 lured, abducted, and murdered Loeb’s 14-year-old cousin Bobby Franks by clubbing and asphyxiation. The duo fancied themselves as master criminals beyond the law—they planned to play a ransom game with the victim’s family, savor the newspaper reportage, and get away with murder. But the body was discovered before the ransom could be collected, and because Leopold lost his rare fashionable glasses at the crime scene, the police traced the two young men in no time.

The Leopold and Loeb case, thoroughly analyzed by the criminology professor and historian Simon Baatz in his recent book For the Thrill of It, was unique in the annals of 1920s violence. The widespread eugenic thinking of the time was that crimes were committed by individuals of low hereditary intelligence. Reformers, on the other hand, saw gangsters as the products of environmental factors like working class poverty and urban tenements. In either case, criminals killed over money, territory, and credibility, their actions a rational business of meeting the demand for illegal goods and services. There was no clinical mystery to their behavior.

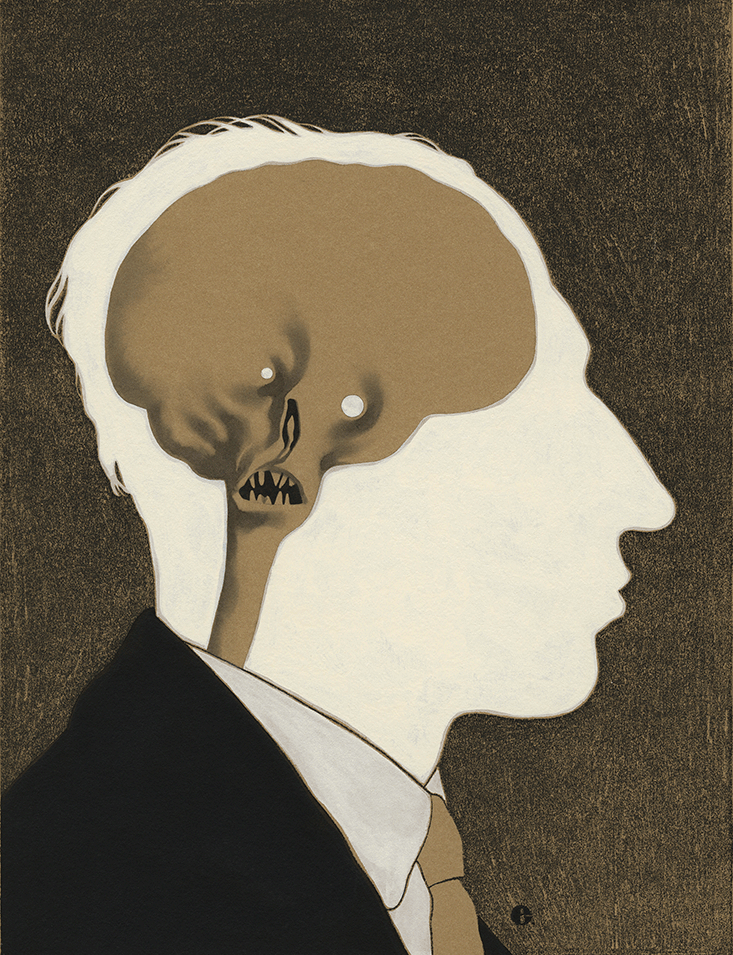

But Leopold and Loeb were different and their case had explosive consequences. It put the very idea of free will and responsibility on trial. People weren’t to blame for their crimes because they were at the mercy of their individual biology. Science said so. Echoes and issues of the spectacular case persist in forensic medicine to this day.

Loeb and Leopold grew up in two of Chicago’s wealthiest and most prominent families. Loeb’s father was a multimillionaire vice president of Sears Roebuck, and Leopold’s owned manufacturing companies and the largest shipping line in the Great Lakes region. Loeb was pursuing postgraduate studies in history and Leopold was already a published ornithologist. The young men were enigmas, their crime an inexplicable whydunnit.

The duo’s attorney, Clarence Darrow, knew the jury wouldn’t accept an insanity defense. Not only did the young men know right from wrong, they had consciously followed the wrong, influenced by Leopold’s reading of Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea of the superman. They freely confessed their careful planning to the police, regarding themselves as amoral criminal masterminds.2 Most scandalously, they showed no remorse. Plus, in the public eye, their erotic king-slave relationship (the sallow Leopold was the self-described powerful slave to the handsome and outgoing Loeb) played against them even in the sexually candid ’20s. The prosecutor, Robert Crowe, was calling for the death penalty. So instead of claiming insanity, Darrow appealed to a new medical specialty to justify his clients’ deed: endocrinology, the science of glands and their secretions.

At the time, medical knowledge was exploding, and the field of endocrinology was extremely powerful among medical elites as well as the laity—it appeared to hold the keys to human health, vitality, and actions. As historian of science Michael Pettit observed in a recent article in the American Historical Review, endocrinology was part of a movement to identify and manage the hereditary and biological foundations of human behavior. At the time, hormones were the building blocks of the new science. The endocrinologist Louis Berman, author of the 1921 bestseller The Glands Regulating Personality, claimed that crimes were linked to hormonal excesses and deficiencies created by adrenal, thyroid, thymus, or pituitary glands, the gonads, or some combination thereof. Some doctors transplanted monkey testes into rich aging patients to restore their youth.3 Others were trying to treat mental illness with extracts from animal glands. Darrow shared a common optimism of the 1920s that the newly discovered role of internal secretions could, in conjunction with psychoanalysis, explain and treat psychopathology. He believed his clients’ glandular abnormality would make the strongest case for leniency.

People weren’t to blame for their crimes because they were at the mercy of their biology. Science said so.

Darrow’s principal expert witnesses, the psychiatrists Howard Hulbert and Karl Bowman, examined the defendants exhaustively and took their detailed psychological histories. Hulbert testified that Nathan Leopold’s pineal gland had calcified prematurely. There were also signs he had suffered from thyroid abnormalities and a disorder of the adrenal medulla. His unusual skull conformation may have crowded his pituitary, and his sex glands indicated an abnormal drive.4 Hulbert argued that while Leopold’s condition did not induce him to plan the murder, it did “remove the ordinary restraint which individuals impose on themselves because of their consciousness of their duties… to society,” and made him unrepentant. While Loeb’s examination had shown no glandular disorders, the “motives… in his subconscious mind” had weakened his self-restraint, making his judgment “childish and uncritical,” Hubert wrote.

The courtroom became a battlefield of experts trying to undermine each other. Determined to send the pair to death row, Crowe called medical experts of his own who testified there was nothing wrong with the defendants neurologically. Rather than attack Hulbert’s glandular findings directly, Crowe browbeat him by revealing his ignorance of the technical details of the X-ray devices that produced the images he interpreted. In turn, the defense tried to discredit Crowe’s psychiatrist witness by showing that the textbook he had written warranted a diagnosis of paranoia for Leopold and schizophrenia for Loeb. In his closing statement, Crowe accused Darrow of trying to undermine all personal responsibility in the name of false science. At the end, Judge John Caverly didn’t buy the gland defense. He dismissed mental illness, including endocrine abnormalities, as a mitigating factor, but spared the duo from the death penalty, sentencing each to 99 years for kidnapping and life imprisonment for murder.5

The big bang of forensic endocrinology had fizzled. But Darrow’s conviction that biological and environmental determinants shape human behavior has never vanished from legal debate. (In 1925, Darrow famously defended the teaching of human evolution in the Scopes Monkey Trial.) The Loeb and Leopold case gave science a foothold in the courtroom and introduced a new type of criminal—the individual psychopath. In 1927, three years after the trial, prominent psychiatrists testified before the New York Crime Commission that the public might be surrounded by individuals capable of wrongdoings for profit and pleasure, who crave attention for their crimes. By the 1930s, Berman was advocating the perfectibility of humanity through universal hormone replacement therapy.

Explaining psychopaths’ actions by biological factors beyond their control—abnormal secretions of malfunctioning glands—launched medico-legal reasoning. As the legal scholar Susan R. Schmeiser recently wrote, “the psychopath became just such a figure—a subject whose essential pathology was precisely his ungovernability and hence his insusceptibility to legal regulation.” Society recognized that some anti-social people could not be deterred by criminal law, so instead of being executed or serving a determinate sentence, they might need to be detained and treated indefinitely. As the French philosopher Michel Foucault, quoted by Schmeiser, put it, “The sordid business of punishing is thus converted into the fine profession of curing.”

Today the role of frontier science in jurisprudence continues, although not without skeptics. As the psychologists John Monterosso and Barry Schwartz recently noted in The New York Times, the United States Supreme Court’s decision of 2005 against the death penalty for minors was based on neurological evidence. The judges ruled that expert evidence had shown that parts of the brain involved in behavior control continue to mature through late adolescence. Monterosso and Schwartz warned about a new tendency—supported by the successor to the X-rays of the 1920s, functional nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (fNMR)—to find abnormalities preventing or impeding self-control. Critics call this excuse “My brain made me do it.” Another psychologist they cite, Edward B. Royzman, has observed that the public is much more willing to credit neuroscientific than psychological explanations for behavior.

More recently, a 21st-century counterpart of endocrinology, the study of the body’s bacteria, which far outnumber our own cells, suggests new avenues of diminished responsibility. “Maybe the microbiome is our puppet-master,” Carl Zimmer, a science correspondent with The New York Times, has suggested. Like the endocrinologists of the 1920s, today’s students of the body’s ecology hope for a new generation of far-reaching therapies. Meanwhile this latest scientific big bang gives a new twist to the forensic questions of Clarence Darrow’s age: Do our bugs make us do it?

Edward Tenner, a visiting researcher at Princeton and Rutgers universities, is the author of Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences, and Our Own Devices: How Technology Remakes Humanity. He is finishing a book on positive unintended consequences.