Think of a cat. Then add scales.

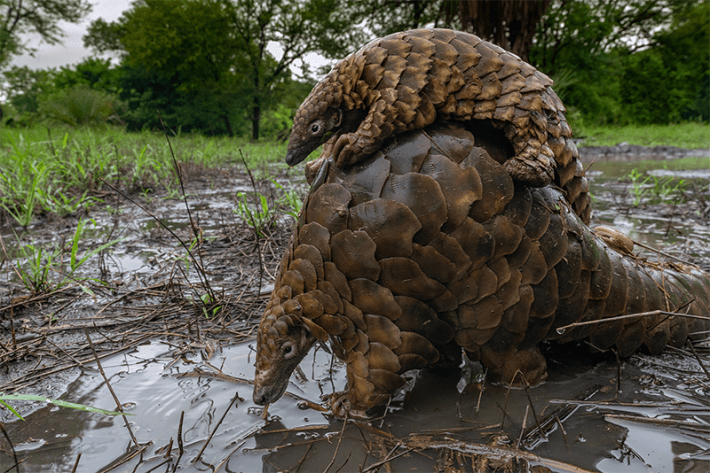

That’s how Mercia Angela describes the pangolins she cares for at the Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, where she runs the country’s only rescue center for the world’s most illegally trafficked mammal. “They sleep a lot,” she says.

Pangolins are nocturnal by nature and elusive in the wild, preferring to burrow in savannas and floodplains, or scrabble up trees in wooded areas where they can remain out of sight. Yet, despite their demure ways, they are the focus of a harrowing drama, their species poached to near extinction by a massive and illegal worldwide trade.

That’s where Angela’s rehab center—and the lush sprawl of Gorongosa as a whole—come in. It’s been a little more than three decades since the ravages of Mozambique’s 15-year civil war, by which time Gorongosa’s population of large mammals had shrunk by 95 percent. Antelope had been slaughtered to feed troops and hundreds of elephants had been killed, their tusks traded for guns. Pangolins didn’t fare any better. For centuries, their meat has been prized as a delicacy in Southeast Asia, and their scales valued in traditional medicinal practices in China. In the West, pangolins barely had a public profile until they were briefly but incorrectly implicated as a possible origin of the COVID-19 virus. Now, because populations in Southeast Asia have been decimated, the pangolins native to sub-Saharan Africa are being caught in poachers’ snares.

The stunned animals roll up and become as compact as a medicine ball, making them easy to scoop up and shove in a sack.

After 30 years of restoration, Gorongosa has become a leading African conservation project, the pangolin rescue one of its central missions. Encompassing 1,500 square miles at the southern end of the Rift Valley, the park may host as many as 75,000 different species of flora and fauna. Among them, the African Ground Pangolin plies its lonely nighttime trade, its excavations making it a sort of gardener providing invaluable rejuvenation of the soil.

Currently, Angela, a wildlife veterinarian, is caring for two pangolins—a baby of only a few months that was rescued from traffickers by Gorongosa’s rangers, and an adult, brought to the center by locals living near the park who were concerned that it, too, might end up ensnared in the trade. The baby—a male that Angela calls Tembo—arrived in September hungry and traumatized. Angela kept him on a diet of milk for three months to help him gain weight before he graduated to ants, which he siphons up at a rate of nearly half a pound a day. She forecasts that in the next few months he might be ready to join the other 98 pangolins Gorongosa has rescued since her center started work in 2018.

The addition of Tembo to that number will be significant. So pervasive is the poaching that the world’s population of pangolins is thought to have dropped by as much as 80 percent over the past two decades alone, the Swiss-based International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has warned.

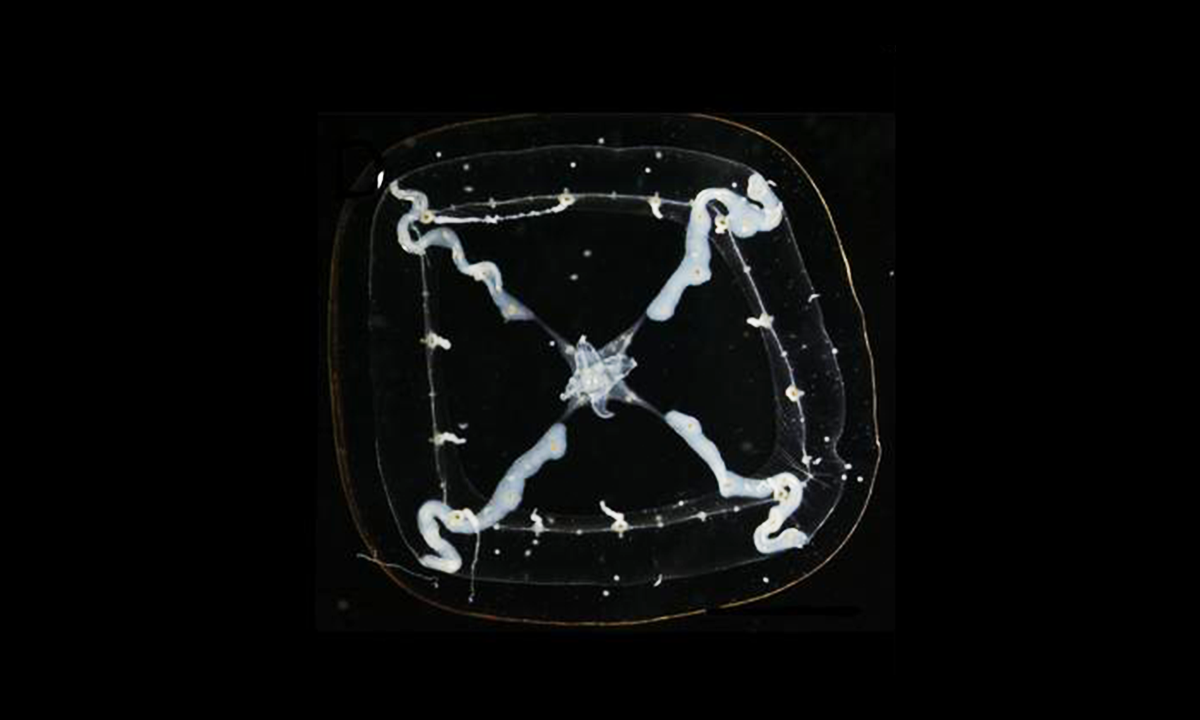

As rare a find as pangolins are, they’re unmissable. Adult pangolins can be as big as raccoons and weigh as much as 40 pounds, but they bear a striking resemblance to an artichoke with legs. Their heads and bodies are riveted with an armor of thorny scales, making them look reptilian. Despite their otherworldly appearance, their scales have a characteristic familiar to every human—they’re made of keratin, the same protein that makes up our fingernails and hair.

In zoological literature, pangolins are loosely referred to as scaley anteaters because of that armor and their diet, but they aren’t related to true anteaters. Rather, they belong to a group all their own—one of the strangest orders of mammals—the Pholidata, which contains only eight living species.

Four of these are found across much of Asia, in countries ranging from India to China, and farther to Malaysia and the Philippines. The other four—including the African Ground Pangolin—are native to sub-Saharan countries stretching from Sudan to South Africa. All of them are at risk of extinction, the IUCN says. The grandest international effort taken against the illegal trade in pangolins came in 2016, when 183 nations signed the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species, known as Cites, which placed all eight species of pangolin in the document’s Appendix I, giving them the strictest protections.

Similar to carnivores by descent and armadillos by convergent evolution, pangolins are most closely related to bears and—yes—cats. But they are almost monastic when compared to those more outgoing cousins. The male and female pangolin come together only to mate, with females capable of giving birth to one baby about every two years. Angela says the single offspring then spend about four months riding on their mother’s tail as they get the hang of hunting. Then they separate and set off for a solitary life all their own, sometimes living as long as 20 years.

And it’s the lonely foraging and burrowing of the African Ground Pangolin that Angela says makes them so essential to the recovery of Gorongosa’s ecosystem. Making quick work of ant and termite hills, pangolins burrow after their prey with deft foreclaws and long, slithering tongues. And where they sniff and nudge the soil by night, nutrients can penetrate more deeply by day, helping to replenish food stores for Gorongosa’s other animals and encouraging rejuvenation of the vegetation.

This appetite has other benefits. Angela says that most adult pangolins can eat about a pound of their quarry in their daily feeding, guarding against destructive termite and ant plagues.

But for all the waste they lay to their prey, pangolins are almost entirely harmless to any other living creature. When this bashful animal is frightened, it curls up into a tight ball, the scales offering its first—and, really, only—line of defense.

Sadly, it’s that defense mechanism that Mercia says makes them so susceptible to capture by traffickers. As poachers drive pangolins into the open by setting fire to their burrows or by battering them out of trees with sticks and clubs, the stunned animals roll up and become as compact as a medicine ball, making them easy to scoop up and shove in a sack.

Often, when poachers are interested only in the scales, they drop the curled-up pangolins into pots of water and boil them alive to make the scales easier to pluck. From there, the scales make their way to Nigeria, where smugglers bundle them with other wildlife contraband like elephant tusks and ship them off to Asia.

Owing to pangolins’ reclusive night-time routines, naturalists have famously been unable to settle on an exact worldwide census for the animals. But the scant handful of national figures that researchers have managed to assemble suggests that there may be fewer than 150,000 left on the African continent, though the question is still open to debate and ripe for more study. Similarly, putting exact numbers to the illegal pangolin trade is challenging, but the most authoritative study, published in 2020 by German biologist Sarah Heinrich and Oxford zoologist Daniel Challender, among others, documented that at least 895,000 had been trafficked from African and Asian countries in the two decades before their study was written, though they conceded the actual number is likely much higher.

Nearly a million pangolins have been trafficked from African and Asian countries in the past two decades.

Heinrich and others shed light on the history and dynamics of the pangolin trade in another paper published that same year. For centuries, various parts of the pangolin anatomy have featured prominently in traditional Chinese medicine—particularly the scales. If those were ground to powder or burned to ash, the old texts held, they could ward off evil spirits and midnight hysterias, provide a salve against ant bites, hemorrhoids and malaria, stimulate lactation in women, and aid in circulation. Western science doesn’t support these claims, but the traditions proved persistent, with more than 200 Chinese pharmaceutical firms offering medicines based on pangolin scales. Indeed, it wasn’t until 2020 that Chinese health insurers stopped covering these remedies.

Pangolins are also a prized delicacy in Vietnam. Challender describes visiting an upscale Ho Chi Minh City restaurant in 2012, where he watched a group of diners pay $700 for a meal consisting of about 4 pounds of pangolin meat. The animal was brought to their table alive, its throat slit in front of them, and its blood was mixed with wine before its flesh was grilled.

But the 2016 study by Henrich highlighted another historic pangolin consumer—the United States. Between 1975 and 2000—when Cites set the export quota for Asian Pangolins to zero, essentially banning the international trade—America was a voracious client of the pangolin’s striking diamond-patterned skin, using it for wallets, handbags, and high-end cowboy boots. Many of these items can still be found on the grayish markets of the internet, though for a stiff price. University of Adelaide professors Joshua Ross and Phill Cassey, in a 2019 paper co-authored with Heinrich, described tracking down a pair of pangolin skin boots for sale on the U.S. eBay site for $13,000. (By May 2023, they had apparently been sold).

In the years since the COVID pandemic, China has established a raft of prohibitions meant to curtail the illegal pangolins trade. But as those focus mainly on pangolin meat, they have not so much dampened the trade as changed its character. Xu Ling, China coordinator for the wildlife trade monitoring group Traffic, told the Guardian that there has been a drop in the number of frozen pangolin carcasses arriving in the country for consumption as meat. Instead, it’s the scales that are smuggled in, which Ling says are harvested in Africa.

And the quantities are on the uptick, a study published in Nature Conservation shows. Researcher James Kehinde Omifolaji of Federal University Dutse in Nigeria and his coauthors combed through arrest records, seizure reports, and other law enforcement data on China’s illicit imports to reach some startling numbers. According to their research, a total of more than 400,000 pounds of pangolin scales made their way to 27 different Chinese provinces in 2021.

Pangolins are lucrative even at the point of sale—or, rather, theft. Angela says that poachers in Mozambique can fetch between $450 to $750 per animal they capture and sell onto the black market.

That may not sound like much, especially considering that Mozambique legislation from May of 2017 establishes a 16-year prison sentence for traffickers, as well as fines dictated by their place in the trade. But in a country that ranks as the eighth-poorest on the Human Development Index, and where average salaries hover around about only $300 a month, the illicit trade in pangolins can seem enticing despite the punishment. Nonetheless, Angela’s charges have fewer worries about smugglers than their brethren outside the park. Watching over them are more than 250 locally hired rangers trained in law enforcement, who patrol the park dismantling snares and keeping tabs on several species with the help of GPS tags. Though the system isn’t fool-proof, park officials say the number of traps they find within park confines has dropped by 60 percent in recent years.

America has been a voracious client of the pangolin’s diamond-patterned skin, using it for high-end cowboy boots.

Because of that, Angela sees the task of her center—and of the Gorongosa Park at large—as something that encompasses more than triage. The Gorongosa park has worked hard to cultivate such community involvement. Some 200,000 people live around the refuge in what park officials call a sustainable development zone that includes education, employment opportunities, and health service. It is for these people that the 15 vets and rangers working in Angela’s center have compiled a how-to guide on caring for distressed pangolins found in the wild, complete with first-aid instructions for animals rescued from poachers. The education and involvement of the community, she says, is critical. An informed public can help alert Gorongosa rangers to vulnerable pangolins located outside the haven of the park, and even point them in the direction of smuggling bands. She points out that the majority of the pangolins that her center has helped rehabilitate were brought to her doorstep by concerned local residents.

Even against long odds for all eight species of Pholidata, it is this communal tendency that gives Angela hope. Ideally, both of Angela’s pangolins will eventually be fitted with GPS trackers and released into the safe haven of the park—a paradise for such threatened creatures.

Picture this: On a recent late afternoon toward sunset, the baby pangolin Tembo and his older bunkmate Mercio (Angela did point out that the elder pangolin’s name is the male spelling of her own) wake from a day of slumber and are ready for food. Angela takes them out of their enclosure and brings them to a nearby grassy field, setting them loose to forage. African Ground Pangolins, unlike the other species, can stand upright on their hind legs, and Tembo and Mercio do—sniffing the air with their sensitive noses for the scent of dinner. Recent rains have brought a bumper crop of ants, and the two burrow in the moist ground and get down to business.

“Yes, there is a light at the end of the tunnel,” Angela says, “A light of hope that with a lot of effort and joint work it is possible to avoid the extinction of this species that is so important in Mozambique.” ![]()

Charles Digges is an environmental journalist and researcher who edits Bellona.org, the website of the Norwegian environmental group Bellona.

Lead photo by Piotr Naskrecki

The Nautilus Gorongosa series is published in partnership with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group.