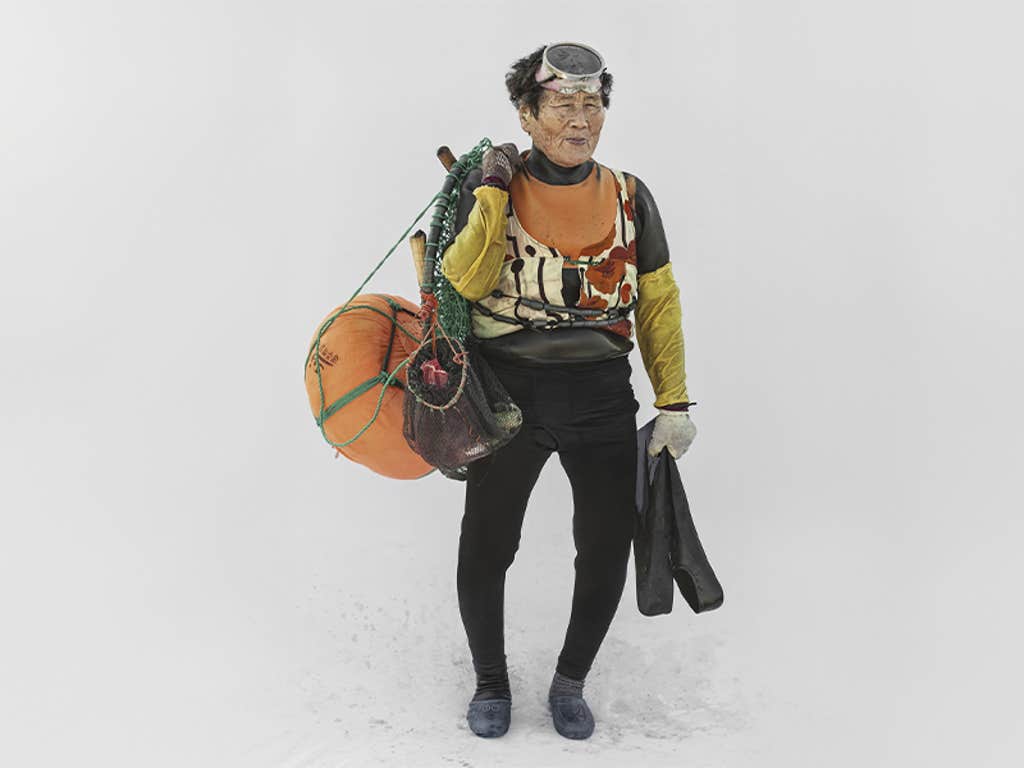

Between 2012 and 2014, Seoul-based photographer Hyung S. Kim frequently visited Jeju Island, which lies off the southern coast of South Korea, to document a small group of women who still carry on an intrepid but dying centuries-old practice.

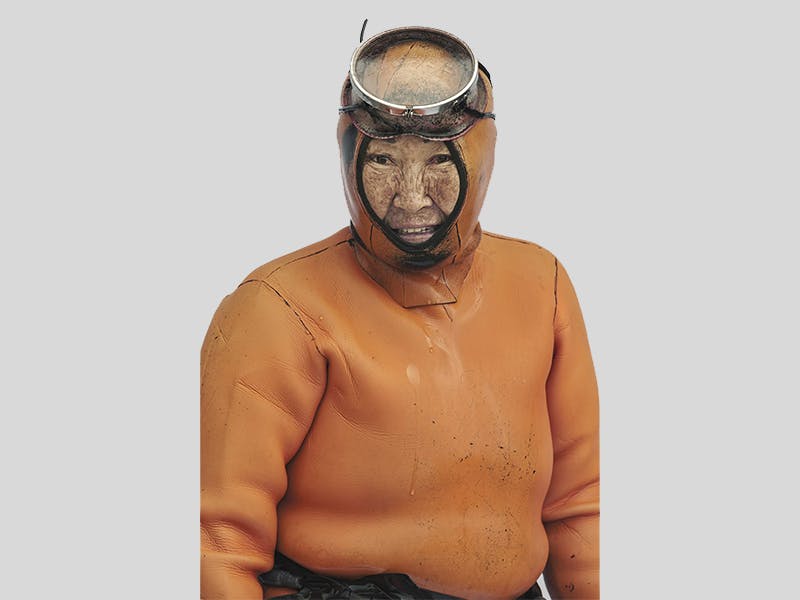

Named the haenyeo—which literally translates to “ocean women”—these iconic divers harvest shellfish and other sea life from deep underwater without oxygen tanks, requiring that they hold their breath for up to 3 minutes. Today, many have passed age 60: The youngest diver Kim photographed was 38 at the time, while the oldest was more than 90.

They might be the last generation of haenyeo.

Captured just after they exited the water, the haenyeo in Kim’s life-size portraits are situated against a stark, white backdrop, which emphasizes their dirt-speckled shoes and wet, shining gear. The equipment they carry includes a tewak—the orange sphere some of them have slung over their shoulders, which floats at the surface during each dive—and lead weights attached to their waists to hasten the descent.

Kim says he was impressed by their strength and power, even in old age, and wanted to preserve their story on film before it is lost. “They might be the last generation of haenyeo, and I wanted to document the beauty of these women,” Kim told Nautilus.

In 2016, the haenyeo were added to the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage as the number of divers has dwindled from around 20,000 in the 1960s to just 2,500 in recent years. Although the work was male-dominated originally, it began to reflect the semi-matriarchal society of the people of Jeju by the 18th century and continues to be led by women today.

In Japan, where the profession is thought to have originated, it is dying, too—in part due to climate change-related depletion of shellfish, and in part due to a loss of interest among younger generations. Here, practitioners are called ama. Some archaeological evidence—ama tools made of deer antlers—suggests the practice is at least 3,000 years old.

You can explore more of the collection of Kim’s portraits on his Instagram page. ![]()

This story is adapted with permission from one that ran in Colossal magazine, and the photographs are reprinted with permission from Hyung S. Kim, all copyright reserved.