The first time I saw a meteor, I’d slipped outside to lie in the grass after everyone else had gone to sleep. The daytime commotion of my cousins’ and siblings’ games and my Poppop’s blaring polka music often drove me to tears. As an introvert, I wanted nothing more than to escape the chaos of my childhood and let the quiet of the night sky comfort me.

I grew up in an economically depressed Pennsylvania coal town as the middle kid in a poor blue-collar family. My parents never read to me or talked about the stars; they were too busy working, my dad as a painter in a factory, and my mother as a short order cook. I spent most of my childhood reading anything I could get my hands on, which wasn’t much—tattered and incomplete set of encyclopedias, the odd science book from my school library, and ragged novels stuffed haphazardly on a shelf in the basement (the best ones were the science-fiction stories). For as long as I could remember, I wanted to leave home to explore strange new worlds and capture them in writing. A high school essay won me a scholarship, which allowed me to go to college and study poetry.

I’m not a physicist. I never studied astronomy in school. For me, the stars are a comforting constant: They are always above me whenever I take the time to look up. In college, I hung out with engineers. My husband is an embedded firmware developer. My older son interned at NASA the past two summers doing robotics research. My younger son is studying environmental science. I’m a nerdy poet surrounded by geeks, so it feels natural to blend poems with stars.

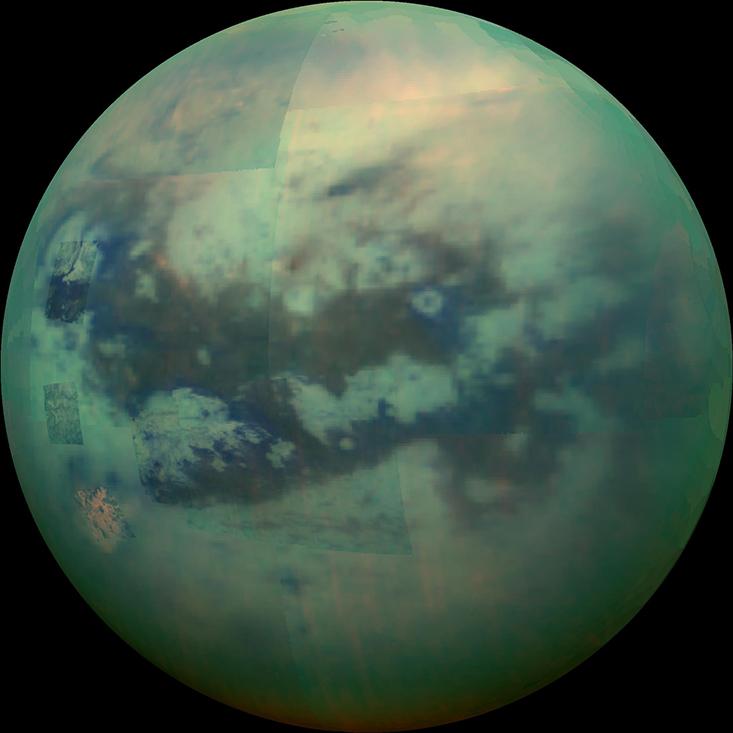

Saturn’s moon may have hidden seas

but here there is only the memory

of her smiling. How the oceanic

dark moved away when she came

near the bed, tucking the covers

around my small body. Moonlight

washing the blankets while I dozed,

her standing outside the door,

dreaming of stars.

Now people have discovered

Titan may have hidden oceans

beneath its ice and my mother

lingers in the hallway until I tuck

her into bed. Sometimes I wait

in the doorway, listen to her breathe

while the stars and moon spin

in the corner of the window;

darkness approaches like the tide.

Come morning I learn there may be

life in those hidden, sunless seas

though my mother sleeps like the dead

in her room. I don’t know if she dreams

because the stars have receded

into blue skies and I am no longer

a child. No longer frightened.

Even on Titan it’s possible the spirit

lingers, concealed though it seems,

spinning in the infinite darkness.

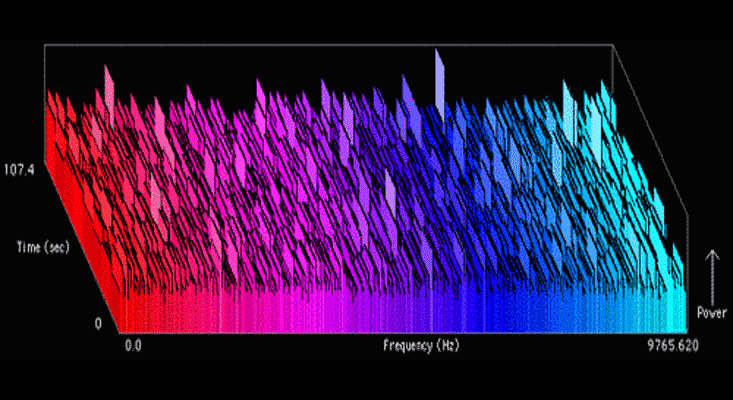

How to search for aliens

At midnight we’d light candles

in the tabernacle and begin

our yearly vigil for the dead.

Mostly I remember the kneeling,

how the vaulted ceiling pressed

the congregation silent until grief

weighted the air. Sometimes I slept

as the incense censer chimed smoke

into strange eddies; often I dreamed

of falling into a vast darkness only to wake

in the pew with tears stepping down my face

as though death had come and gone in the space

of an hour. Even then I knew the spirit shunned

this drama, the artificial quiet shrouding the voice

of god in ritual while outside the planet spun

unperturbed. Four point five billion years

since genesis and the sky still hovers

like a veil between us and space,

wanting to be lifted before the unintelligible

babble dismantles the tower we have

half-built. At Arecibo, signals fall

from the dark like angels dropping messages;

there are miracles in the data waiting for discovery,

contact unrealized despite centuries of squinting

into the heavens. When our vigil ended we would walk

home in the cold, my mother mourning the past

while I tracked the stars that winked between

the street lights, listening for serendipity

in between footsteps. She held my hand so tightly,

perhaps she knew that prayer was too simple:

not enough prime numbers hidden in the signal,

no small man standing on our solar system,

peering out into the universe.

A daylight eclipse of Venus

I couldn’t tell which came first, the moon

or Venus tailing that dusky crescent

like an afterthought. From here,

the tiny eclipse of the planet seemed

fuzzy, not quite real against the enormity

of space and the satellite that hovered

above like an inscrutable god. Later

I read that Venus rose from the sea

centuries ago. Seems she has always

been here, rising at dawn, putting us

to sleep again in the dusk, constant

despite how small she seems against

the moon. I guess she believes

we’ll figure her out eventually as we peer

down into her atmosphere, the Magellan

spacecraft circling her body like a girl

asking her mother for sweets. Perhaps

there’s more to her than the rocky,

volcanic skin she keeps shrouded

so tightly, but I know those secrets

cannot be easily answered so long

as we remain planet-bound, content

to gaze instead of fly.

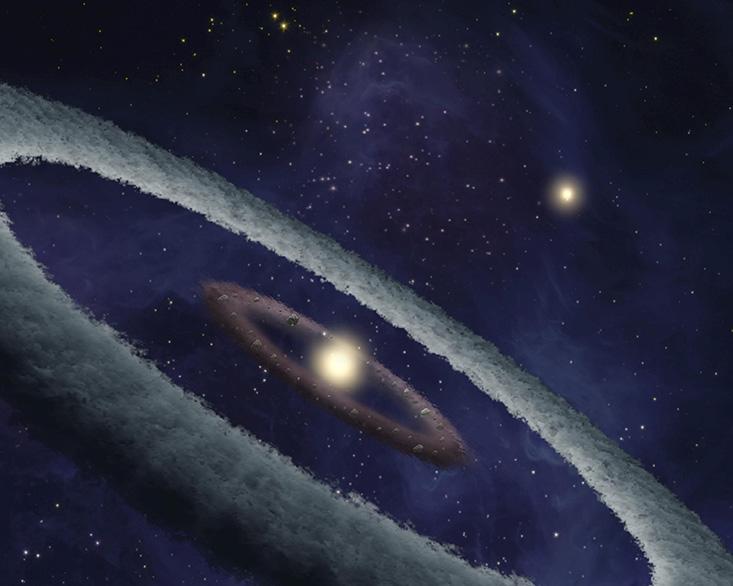

Birth of a planet

You smile when you wake me up.

Planetesimals may be forming

four hundred thirty light years away

but I don’t leave the bed until the tea

you made is ready and sunrise spills

into the house. For verisimilitude

I pretend I am grown and help the boys

choose clean shirts, kiss you goodbye.

Inside I am seventeen and reading about

Earth-like planets and the possibility of life

elsewhere. I have seen an artist’s conception

of a binary star system: dust rings orbiting

the closer sun, planets forming as if right

now is the right moment. Astronomers believe

water may exist in the white outer ring of dust

that looks strangely beautiful in that darkness.

Where anything could happen in a billion years.

Christine Klocek-Lim is an editor, novelist and prize-winning poet who received the 2009 Ellen La Forge Memorial Prize in poetry. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and was a finalist for 3 Quarks Daily’s Prize in Arts & Literature, among others.

“Saturn’s moon may have hidden seas” first appeared in the 2009 Ellen La Forge Poetry Prize Annual, and later in Astropoetica. “How to search for aliens” first appeared in the 2009 Ellen La Forge Poetry Prize Annual, and later in Three Quarks Daily. These poems are from the collection Dark Matter (Aldrich Press, 2015).

This article was originally published on Nautilus Cosmos, in November 2016.