Real life starts in graduate school. Some mornings in West Lafayette, Patricia Westerford’s luck scares her. Forestry school: Purdue pays her to take classes she has craved for years. She gets food and lodging for teaching botany, something she’d gladly pay to do. And her research demands long days in the Indiana woods. It’s an animist’s heaven.

By her second year, the catch becomes clear. In a forest management seminar, the professor declares that windthrow should be cleaned up and pulped, to improve forest health. That doesn’t seem right; a healthy forest needs dead trees. They’ve been around since the beginning. Birds use them, and small mammals. More forms of insects live on them than science has counted. She wants to raise her hand and say, like Ovid, how all life is turning into other things. But she doesn’t have the data.

Soon, she sees. Something is wrong with the entire field. The men running American forestry dream of producing straight, clean grains at maximum speed. They speak of thrifty young forests and decadent old ones, of mean annual increment. These men will have to fall, next year or the year after. And up from the downed trunks will spring rich new undergrowth. That’s where she’ll thrive.

She preaches this covert revolution to her undergrads. “You’ll look back in twenty years, amazed at what every person in forestry took to be self-evident. It’s the refrain of all good science: ‘How could we not have seen?’ ”

She abides her fellow grads. She goes to the barbecues and smiles at departmental gossip while remaining her own sovereign state. One night there’s a dizzy, wild misunderstanding with a woman in plant genetics. Patricia puts the embarrassed fumble away in her heart’s drawer and never takes it out again.

A suspicion sets her apart from the others. She’s sure, on no evidence whatsoever, that trees are social. Motionless things that grow in mass communities must have evolved ways to synchronize. Nature knows few loner trees. But the belief leaves her marooned. Here she is, with her people, at last, and even they can’t see the obvious.

His sigh is as clear as a public service announcement: Girls doing science are like bears riding bikes.

Purdue gets hold of a prototype quadrupole gas chromatography-mass spectrometer. With such a device, she can measure which volatile organics the grand old eastern trees exude and what these gases do to the neighbors. She pitches the idea to her advisor. People know nothing about the stuff trees make. It’s a green world, ripe for discovery.

“How will that produce anything useful?”

“It might not.”

“Why do this in a forest? Why not the campus test plots?”

“You wouldn’t study wild animals by going to the zoo.”

“You think cultivated trees behave differently than trees in a forest?”

She’s sure of it. His sigh is as clear as a public service announcement: Girls doing science are like bears riding bikes. Possible, but freakish.

The work consists of taping plastic bags over the ends of branches, then collecting them at intervals. She does this over and over, hour by hour, while the world around her rages with assassination, race riot, and jungle warfare. She works all day in the woods, her back crawling with chiggers, her scalp with ticks, her mouth filled with leaf duff, her eyes with pollen, cobwebs like scarves around her face, bracelets of poison ivy, her knees gouged by cinders, her nose lined with spores, the backs of her thighs bitten Braille by wasps, and her heart as happy as the day is generous.

She brings the samples to the lab and spends tedious hours determining which gases each of her trees exhale. There must be thousands of compounds. The tedium makes her ecstatic. She calls it the science paradox. It’s the most brain-crushing work a person can do, yet it can spring the mind to see what else is out there. And she gets to work in the sun and rain, the stink of humus filling her nose with musky life.

Back in the lab, she finds something even she isn’t ready to believe.

It’s a miracle, she tells her students, photosynthesis. All the razzmatazz of life on Earth is a free-rider on that mind-boggling magic act. She leads her charges into the heart of the mystery: Hundreds of chlorophyll molecules assemble into antennae complexes. Countless antennae arrays form into thylakoid discs. Stacks of these discs align in a single chloroplast. Up to a hundred such solar power factories power a single plant cell. Millions of cells may shape a single leaf. A million leaves rustle in a single ginkgo.

Too many zeros: their eyes glaze over. She shepherds them back over that ultrafine line between numbness and awe. “Billions of years ago, a single, fluke, self-copying cell learned how to turn a barren ball of poison gas and volcanic slag into a garden. And everything you hope, fear, and love became possible.” They think she’s nuts; that’s fine with her. She’s content to post a memory forward to their futures, futures that will depend on the generosity of green things.

Late at night, spent from teaching and research, she reads her beloved Muir. His prose floats her soul up to her room’s ceiling. She writes her favorite lines inside the covers of her field notebooks and peeks at them when the cruelty of frightened humans get her down.

The clearest way into the universe is through a forest wilderness.

Plant-Patty becomes Dr. Pat Westerford, a way to disguise her gender in professional correspondence. Her work on tulip trees earns her a doctorate. It turns out that those thick, long lengths of vertical culvert are richer than anyone suspects. Liriodendron breathes out a repertoire of organic compounds that do all kinds of things. She doesn’t yet know how the system works. She just knows it’s rich and beautiful.

She lands a postdoc at Wisconsin. The postdoc turns into an adjunct position. She makes almost nothing, but life requires little. Her budget is blessedly free of those two core expenses, entertainment and status. And the woods teem with free food.

She studies sugar maples, in a forest east of town. Her breakthrough comes as breakthroughs often do: by long-prepared accident. Patricia arrives in her copse one June day to find one of her bagged trees under full-scale insect invasion. The last several days of data seem to be ruined. Improvising, she keeps the samples from the damaged tree, as well as several nearby maples. Back in the lab, she finds something even she isn’t ready to believe.

Another nearby tree gets infested. She measures again. Again, she doubts the evidence. Fall begins, and the leaves of her chemical factories drop to the forest floor. She battens down for winter, double-checking her results, trying to accept their crazy implications. She wanders the woods, wondering if she should publish or measure for another year. The oaks in her forest shine scarlet, the beeches a stunning bronze. It seems wise to wait.

The opinion of others left her ready to suffer the most agonizing death.

Confirmation comes the following spring. The trees under attack pump out insecticides to save their lives. That much is uncontroversial. But something else in the data makes her flesh pucker: trees a little way off, untouched by the invading swarms, ramp up their own defenses when their neighbor is attacked. They somehow get wind of the disaster and prepare. She controls for everything, and the results are always the same. Only one conclusion makes sense: wounded trees send out alarms that other trees smell. Her maples are linked together in an airborne network, sharing an immune system across acres of woodland. These brainless, stationary trunks protect each other.

She can’t quite believe. But the data keep confirming. On that evening when Patricia finally accepts the measurements, her limbs warm and tears run down her face. She may be the first creature in the expanding adventure of life ever to glimpse this small, certain thing that evolution made. Life is talking to itself, through her.

She writes up the results as soberly as she can. Chemistry, concentrations, and rates—nothing but what the gas chromatography equipment records. But in her paper’s conclusion, she can’t resist suggesting what the results spell out: The biochemical behavior of individual trees may make sense only when we see them as members of a community.

A reputable journal accepts her paper. The peer reviewers raise their eyebrows, but her data are sound and no one can find any problems except common sense. On the day the article appears, Patricia feels she has discharged her debt to the world. If she dies tomorrow, she’ll still have added this one small thing to what life has come to know about itself.

The press latches onto her findings. She does an interview for a popular magazine. She struggles to hear the questions over the phone and stumbles with her answers. But the piece runs, and other newspapers reprint it. “Trees Talk to One Another.” She gets letters from other researchers, asking for details. She’s invited to speak at the midwestern meeting of the professional forestry society.

Four months later, the journal that ran the piece prints a letter signed by three leading dendrologists. The men say her methods are flawed and her statistics problematic. The defenses of the intact trees could have been activated by other mechanisms. Or these trees might already have been compromised in ways she didn’t notice. The letter mocks the idea that trees send each other chemical warnings:

Even if a message is in some way “received,” it would not imply that any message has been “sent.”

Two Yale professors and a name chair at Northwestern, versus an adjunct girl at Madison: No one in the profession bothers replicating Patricia Westerford’s findings. Researchers who wrote her for more information stop responding to her letters. Newspapers that ran wide-eyed articles follow up with accounts of her brutal debunking.

Patricia goes through with her talk at the midwestern forestry conference, in Columbus. The room is small and hot. Her hearing aids howl with feedback. Her slides jam in the carousel. Fielding hostile questions from behind the podium, Patricia feels her childhood speech defect returning to punish her for her hubris. For three agonizing days, people nudge each other as she passes in the halls of the conference hotel: There’s the woman who thinks that trees are intelligent.

She has always scared people. Fear has its uses. The stepstool to wonder.

Madison doesn’t renew her lectureship. She scrambles to line up a job elsewhere, but she can’t even get work washing glassware. No other animal closes ranks faster than Homo sapiens. Without a lab, she can’t vindicate herself.

At thirty-two, she starts high-school substitute teaching. Meaning drains from her like green from an autumn maple. After months in solitude replaying what happened, she decides it’s time to shed.

She’s too cowardly to give in to the scenarios that play in her head most nights as she lies sleepless. The pain prevents her. Not hers: the pain she’d inflict on her mother and brothers and remaining friends. Only the woods can help her. She tramps the winter trails, feeling the thick, sticky horse chestnut buds. She listens to the forest, the chatter that has always sustained her. But all she can hear is the wisdom of crowds.

Half a year passes at the bottom of a well. One crisp blue summer Sunday, Patricia finds several unexpanded caps of Amanita bisporigera in the bottomlands of Token Creek. She gathers them in her mushroom bag and brings them home. There, she cooks up a Sunday feast for one: chicken tenderloins in butter, garlic, shallots, and white wine, all seasoned with enough Destroying Angel to shut down both kidneys and liver.

She sits to a meal that smells like health itself. The beauty of the plan is that no one will know. Every year, amateur mycologists mistake young A. bisporigera for Agaricus silvicola or even Volvariella volvacea. No one will think anything but this: She was wrong in her controversial research, and wrong in her choice of fungal fruiting bodies for her dinner.

She brings the steaming forkful to her lips. Something stops her. Signals flood her muscles, finer than words.

Not this. Come with. Fear nothing.

The fork drops back to the plate. She rouses as from sleepwalking. Fork, plate, mushroom feast: everything turns, as she watches, into a fit of madness, lifted. The opinion of others left her ready to suffer the most agonizing death. She runs the entire meal down the disposal and goes hungry, a hunger more wonderful than any meal. Nothing in the years to come can do worse than she was ready to do to herself. Human estimation can no longer touch her. She’s free now to experiment. To discover anything.

From the outside, yes: Patricia Westerford disappears into underemployment. Sorting storeroom boxes. Cleaning floors. Odd jobs leading from the Upper Midwest through the Great Plains toward the high mountains. All her old friends add her to the roster of science roadkill. In fact, she’s busy learning a foreign language. With few claims on her time and none on her soul, she turns back into the woods, the green negation of all careers. She no longer theorizes or speculates. Just watches, notes, and sketches into a stack of notebooks, her only persistent possessions. Her eyes go near and narrow. She camps out many nights, under the spruce and fir, sleeping on thick beds of brown needle pillow, the living earth beneath her bag, its fluid influence rising up into her fiber.

She drifts farther west. It’s amazing how far a little war chest will go, once you learn how to forage. She glimpses her own face once, splashing water on it in the bathroom of a service station near a national forest in a state where she’s the merest beginner. She looks weathered, old beyond her years. She has gone to seed. Soon she’ll start scaring people. So be it. She has always scared people. Fear has its uses. The stepstool to wonder.

Science has come to drag her back, like Persephone, to the world of humans.

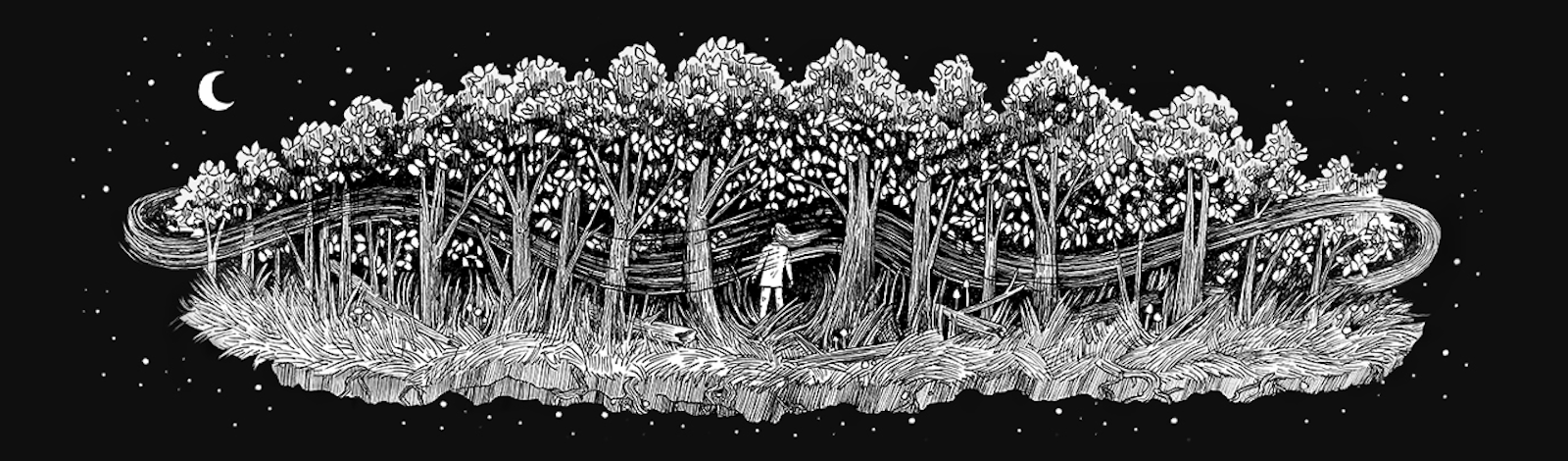

In the early eighties, Patricia heads northwest. Giants still grow there, in pockets of old growth scattered from Northern California on up to Washington. She wants to see uncut forest, while there’s some left to see. The western Cascades in a damp September: nothing prepares her. From mid-distance, with no clue for scale, the trees seem no larger than the biggest sycamores and tulip poplars out East. But up close the illusion disappears, and all she can do is look and laugh and look some more.

Hemlock, grand fir, yellow cedar, Douglas-fir: Monster conifers disappear in the mist above. Sitka spruces bulge out in burls as big as minivans—pound for pound, a wood stronger than steel. A single trunk could fill a logging truck. Even runts here would dominate an eastern forest, and each acre holds five times as much wood. Beneath these giants, way down in the understory, her own body seems freakishly small, like one of those acorn-people she made in childhood.

Chatter disturbs the cathedral hush. The air is so twilight-green she feels like she’s underwater. It rains particles—broken webs and mammal dander, skeletonized mites, insect frass and bird feather … Everything climbs over everything else, fighting for scraps of light. If she holds still too long, vines will overrun her. She walks, crunching ten thousand invertebrates with every step, watching for tracks in a place where at least one of the native languages uses the same word for footprint and understanding. The earth gives beneath her like a shot mattress. She swings her singing stick, and the temperature plummets as she passes through a thermal curtain. The canopy is a colander stippling the beetle-swarmed surfaces with specks of sun. Sword fern, liverworts, lichen, and leaves as small as sand grains stain every inch of the dank, downed logs. The mosses are as dense as thumbnail forests.

She presses on bark fissures and her fingers sink in. The rot is prodigious. Creature-riddled boles, decaying for centuries. Twisted snags, silvery as inverted icicles. The scent of ever-dying life woven together with fungal filaments and dew-betrayed spiderweb leaves her woozy. Mushrooms climb the sides of trunks in terraced ledges. Soaked by fog all winter long, spongy green stuff she can’t name covers every wooden pillar in thick baize.

She sees the source of that forestry doctrine she so resisted in school. Looking at all this glorious decay, a person might be forgiven for thinking that old meant decadent, that such thick mats of decomposition were cellulose cemeteries in need of the rejuvenating ax. Her kind will always dread these close, choked thickets, where solo trees give way to massed, crazed tangles. There are things in here worse than wolves and witches, primal fears that no amount of civilizing will ever tame.

Prodigious dying pulls her along, past an immense western red cedar. Her hand strokes the fibrous strips that peel from a colossal, fluted trunk reeking of incense. The top has sheared off, replaced by a candelabra of stand-in trunks. A grotto opens at ground level in the rotted heartwood, big enough for whole families of mammals. But the scaly sprays of branches, a thousand years on, still teem with cones. She addresses the cedar, in words of the forest’s first humans. “Long Life Maker. I’m here. Down here.” She feels foolish, at first. But each word is a little easier than the next.

“Thank you for the baskets and the boxes. Thank you for the capes and hats and skirts. Thank you for the cradles. The beds. The diapers. Canoes. Paddles, harpoons, and nets. Poles, logs, posts. The rot-proof shakes and shingles. The kindling that will always light.”

Finding no good reason to quit now, she lets the gratitude spill out, following the ancient formula. “Thank you for the tools. The chests. The decking. The closets. The paneling. I forget … Thank you for all these gifts that you have given.” Not knowing how to stop, she adds, “We’re sorry. We didn’t know how hard it is for you to grow back.”

She finds work with the Bureau of Land Management. Wilderness ranger. The job description seems as miraculous as the outsized trees: Help preserve and protect for present and future generations places where man is a visitor who does not remain. She must don a uniform. But they pay her to be alone, carry the welcome weight of a pack, read a topo map, dig a water bar, look for smoke and fire, follow the rhythms of the land, and live wholly within the arc of the year. To clean up after humankind, yes. To gather the endless twisties, six-pack rings, cans, and bottle caps strewn through meadows of wildflower, on remote scenic outlooks, and in cold running streams. It’s expiation.

Her supervisor apologizes for the cabin they give her, on the edge of an ancient cedar grove. There’s no running water, and the varmint biomass outweighs her, many times over. She laughs at their embarrassment. It’s the Alhambra.

She works for eleven blissful months. The wildlife never once threatens her, and deranged campers do so only twice. Monster trees suck up the downpour and respire it back into the air as steam. In the constant rain, everything grows mold. Spores spread across every damp surface. Both her legs sport athlete’s foot up to the knees. Sometimes, when she closes her eyes, she feels that moss will cover her lids by the time she opens them again.

While she rehabs backcountry fire rings and cleans up illegal campsites fouled with beer cans and toilet paper, an article appears. It’s published in a reputable journal, one of the best that humankind has managed. Trees trade airborne aerosol signals, the article says. Their fragrances alert their neighbors. They can sense an attacking species and summon an air force to come to their aid. The authors cite Patricia’s earlier, much-mocked article. They reproduce her findings and extend them into surprising places. Words of hers that she has all but forgotten have gone on drifting, signals on the open air.

Out one day in a nearby drainage, sawing windthrow from a remote trail, Patricia sees a motion in the undergrowth. It’s a couple of vagabond scientists from that loose confederation who gather every summer in the flimsy trailers full of lab gear in a clearing three miles from her own cabin. She dreads these run-ins with her old tribe, always saying as little as possible. Today, she holds back and watches. Through the woods, the two men look like upright circus animals in lumberjack costumes.

One of the men hoots softly, a perfect impersonation. She has often heard the call at night but has never seen the caller. The man calls again. Incredibly, something answers. A duet ensues: the bright, pert come-on, followed by the logy, obliging bird. A streak in the air, and the creature appears, the first Strix occidentalis Patricia has ever seen. Spotted owl. It settles, mythic, on a branch three yards from its seducers. Bird and men regard each other. One species takes pictures. The other just spins its head and blinks its enormous eyes. Then the owl is gone, followed, after further note-taking, by the humans, leaving Patricia Westerford wondering if she wakes or sleeps.

Three weeks later, she’s near the same spot, pulling invasive plants. The furry ailanthus suckers leave her fingers stinking of coffee and peanut butter. She climbs a switchback at a good clip and runs into the two researchers, several yards up the slope, kneeling by a downed log. Before she can flee, they see her and wave. Caught, she waves back and hikes up to them. The older man is on the ground, on his side, popping tiny creatures into specimen bottles.

“Ambrosia beetles?” Two heads turn toward her, startled. Dead logs: her passion once, and she forgets herself. “When I was a student, my teacher told us that fallen trunks were nothing but fire hazards.”

The man on the ground stares up at her. “Mine said the same thing.”

“ ‘Clear them off to improve forest health.’ ”

“ ‘Burn them out for safety and cleanliness.’ ”

“ ‘Lay down the law and get the stagnant place producing again!’ ”

All three chuckle. But the chuckle is like pressing on a wound. Improve forest health. As if forests were waiting these four hundred million years for people to come cure them. Science in the service of willful blindness: How could so many smart people have missed the obvious? A person has only to look, to see that dead logs are far more alive than living ones. But the senses never have much chance, against the power of doctrine.

“Well,” the man on the ground says, “I’m sticking it to the old bastard now!”

Hope pushes through Patricia, like a breeze through rain. “What are you studying?”

“Fungi, arthropods, reptiles, amphibians, small mammals, frass, webs, denning, soil. … Everything we can catch a dead log doing.”

“How long have you been at it?”

The two men trade looks. The younger man hands down another sample bottle. “We’re six years in.”

“Six years?” In a field where most studies last a few months. “Where on earth did you find funding?”

“We’re planning to study this particular log until it’s gone.”

She laughs again, a little wilder. A cedar trunk on the wet forest floor: their grad students’ great-great-great-grandchildren will have to finish the project. Science, in her absence, has gone as crazy as she always thought it should be.

The man on the ground sits up. “Dr. Westerford?”

She blinks, as baffled as any owl. Then she remembers her uniform badge, there for anybody to read. But Dr. He could only have gotten that from her buried past. “I’m sorry,” she says. “I don’t remember meeting you.”

“You haven’t! I heard you talk, years ago. Forest studies conference, in Columbus. Airborne signaling. I was so impressed, I ordered offprints of your article.”

That wasn’t me, she wants to say. That was someone else, lying dead and rotting somewhere.

“They hit you pretty hard.”

She shrugs. The younger scientist looks on like a kid on a visit to the Smithsonian.

“I knew you’d be vindicated.”

Her bewilderment is enough to tell him what she’s doing here. Why she’s in the uniform of a wilderness ranger.

“Patricia. I’m Henry. This is Jason.” His voice is soft but urgent, like there’s something at stake. And she knows what it is, before he can say. The story reaches her, on airborne pheromones. Science has come to drag her back, like Persephone, to the world of humans. “Come visit the station. You’ll want to learn what your work’s been up to, while you were gone.”

Richard Powers is the author of 12 novels, most recently The Overstory. He is the recipient of a MacArthur grant and the National Book Award, and he has been a Pulitzer Prize and four-time National Book Critics Circle finalist. He lives in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains.

Excerpted from The Overstory: A Novel by Richard Powers. Copyright © 2018 by Richard Powers. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.