More than 100 million years ago, huge marine reptiles might have chomped down on marlin-like fish, violently thrashing their prey until their heads ripped off, according to fossils that were recently analyzed.

Researchers studied more than 300 fossils belonging to Aspidorhynchus, a genus of extinct fish, from a large region of Germany that was once a series of islands scattered throughout a shallow sea. The area is recognized for yielding particularly well-preserved fossils from the Late Jurassic, which stretched from about 160 million to 145 million years ago.

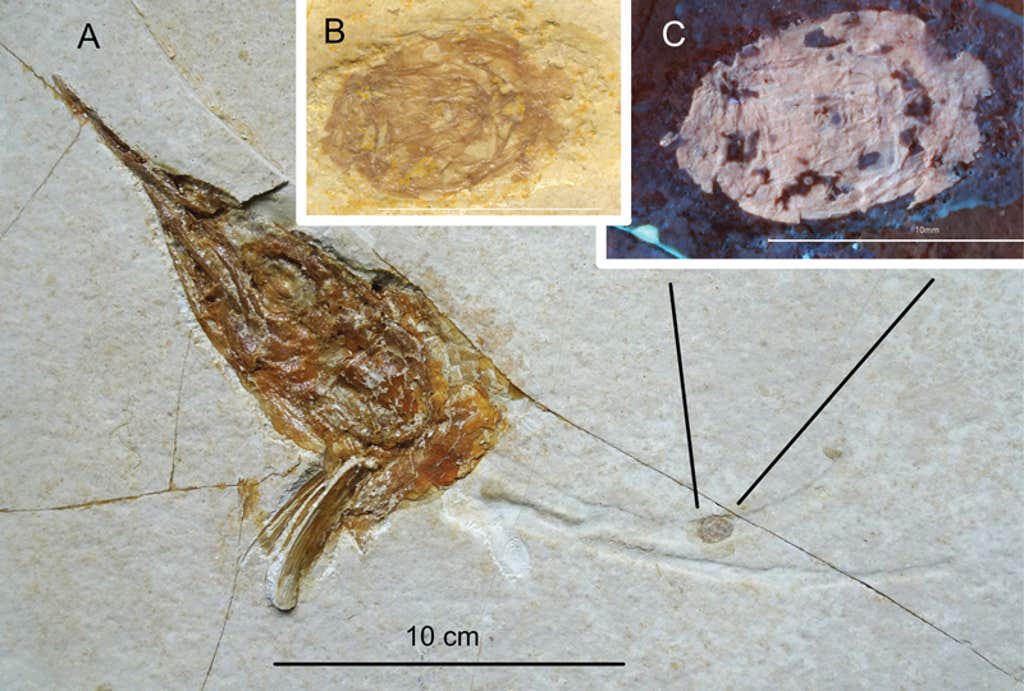

Among this collection were 10 disembodied Aspidorhynchus heads with guts still attached, according to a new study published in Fossil Record. These gory scenes, frozen in evolutionary time, are “extraordinary fossils” and “unique in the fossil record,” the authors wrote.

Aspidorhynchus measured up to some 3 feet long and had a long, sword-like upper jaw—like the swordfish or marlins you may have spotted decorating the walls of a seafood restaurant. Aspidorhynchus and other members of its family were some of the heftier predatory fish commonly found in this Late Jurassic aquatic ecosystem in modern-day Germany.

In previously discovered Aspidorhynchus fossils, the creatures’ gastrointestinal tracts were obscured by thick scales. But with a rare look inside their guts, scientists learned more about the Aspidorhynchus diet. They found out that these pointy fish seemed to munch on small teleosts, which are related to many extant fish species, by eating them whole and head-first. The researchers suggest that Aspidorhynchus hunted similarly to today’s swordfish, using their sharp upper jaws to slash at schools of prey. One specimen hinted that they sometimes went for larger meals, like a 6-inch-long Allothrissops fish.

Read more: “The Rise and Fall of the Living Fossil”

The decapitated fossils also offered clues behind their grisly demise: They may have been hunted by “grabber” predators including large reptiles, who would “seize their prey tail-first and crippling or even killing it by means of vehement headshakes and bites,” the study authors wrote. Then, these grabbers may have let go, recaptured, and gobbled up their victims. The predators probably consumed the most nutritious bits that demand the least amount of work first, so it’s possible that they left the Aspidorhynchus heads and let them sink into the depths with guts still intact.

Aspidorhynchus’ heads also seem vulnerable to decaptiation—their vertebrae are relatively soft and may have proved easy to bite through. And if a predator “cut the head at the dorsal connection with the spine then pull the head off,” then “the guts come with it,” according to a quote from David Bellwood, a marine biologist at James Cook University in Australia, included in the paper.

This would be an easy feat for huge reptiles such as ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs, some of which exceeded 13 feet long, offering terrifying new insights into the aquatic wild west of the Late Jurassic. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Nobu Tamura / Wikimedia